(Stonewall Uprising is now available on DVD through PBS/American Experience. It was released theatrically by First Run Features in over 20 cities in the US and opened at New York’s Film Forum for a one-week engagement Wednesday, June 16, 2010, with the filmmakers and some of the subjects in attendance on opening night. It also aired on PBS’s American Experience in the spring of 2011.)

In 1969, homosexual acts were illegal in every state in the US, except Illinois. Gay people had no political power, no rights. Kate Davis and David Heilbroner, a prolific husband and wife documentary filmmaking team based in New York City, were commissioned by PBS’s American Experience to make a film about the now-famous Stonewall riots that took place in New York’s West Village in the summer of that year. But before we even get to the recreation of that event, accompanied by commentary from some of the men and women who were there, Davis and Heilbroner meticulously and expertly illustrate the timbre of the general populace’s views on homosexuality, aided and abetted by vicious and incendiary propaganda about the dangers to society for which these “deviants” might be responsible, especially to young boys and girls vulnerable to encountering homosexuals in their schools, neighborhoods and playgrounds.

Stonewall Uprising opens with various selections of archival materials that showcase the ways in which this “mental defect” or “psychopathy” could threaten normal families. As responsible Americans, we had to be vigilant about watching for any suspicious behavior in our little boys and girls and “correct” any aberrant tendencies immediately. From the public service announcement produced and released by the Albert Einstein School of Medicine called Boys Beware (1961), to CBS Reports’s news hour The Homosexuals (1967, hosted by Mike Wallace), to footage of Detective John Sorenson of the Dade County Morals & Juvenile Squad scaring the wits out of junior high school students about what will happen to them if they’re caught being “homosexual”—these outrageous and fear-mongering pieces show us that if you were growing up gay in the 1950s and 1960s, you could be subjected to arrest and personal ruin (with your full name and home address appearing in the newspapers), sterilization, castration, electroshock therapy, lobotomy, and so-called “medical experimentation” at the hands of clinicians and doctors. One subject remembers a place in Atascadero, California, where parents sometimes sent their wayward children, recalling that the facility, placed in the middle of nowhere, was known as “the Dachau for queers.”

In this atmosphere, young closeted gay people flocked to havens like New York City’s Christopher Street and San Francisco’s Castro District to find a friendly and open environment where they could be “out” and amongst their own kind, even though one subject tells us that, before Stonewall, there was no such thing as being, or coming, out. “There was just in.” The gays called themselves the “twilight people,” only appearing on the streets well after dark, hiding in the shadows, ever fearful of beatings by roving gangs out for a night of sport at their expense, or being harassed, beaten, arrested, and jailed by police. They had very few public places of refuge. One subject tells us, “Gay bars were to gay people what churches were to black people in the South.” In fact, Stonewall is described as their “Rosa Parks moment, when the system of oppression started to crumble.”

In this atmosphere, young closeted gay people flocked to havens like New York City’s Christopher Street and San Francisco’s Castro District to find a friendly and open environment where they could be “out” and amongst their own kind, even though one subject tells us that, before Stonewall, there was no such thing as being, or coming, out. “There was just in.” The gays called themselves the “twilight people,” only appearing on the streets well after dark, hiding in the shadows, ever fearful of beatings by roving gangs out for a night of sport at their expense, or being harassed, beaten, arrested, and jailed by police. They had very few public places of refuge. One subject tells us, “Gay bars were to gay people what churches were to black people in the South.” In fact, Stonewall is described as their “Rosa Parks moment, when the system of oppression started to crumble.”

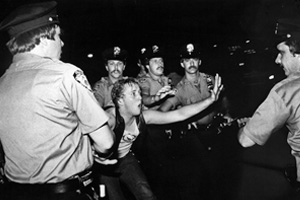

These dark and ignorant ages were not so very long ago, remember—just a handful of decades, in fact. To this day, in many ways and in many places, there is still not much in the way of basic rights for gay people to live openly, safely, securely in this country, free from ostracism and humiliation. In illustrating an atmosphere of dread, fear and suspicion, not to mention gross malfeasance on the human rights front, Stonewall Uprising sets the stage for that hot summer night on June 28, 1969, when New York City police, once again, raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich Village. But for the very first time on this particular evening, the gay community finally organized, en masse, and fought back with a vengeance.

This was at the height of many national Civil Rights movements in the United States—on the part of blacks, on the part of women, on the part of every marginalized segment of society that started demanding from their government, whose job it was to hold up the tenets of the nation’s Constitution, to “get off our backs and deliver on the promise” of protecting the rights of every member of its citizenry. Everything started erupting in 1968: that summer in Chicago saw an historical protest outside the Democratic National Convention. 1969 was the year of a mayoral re-election campaign for Republican John Lindsay that brought a major crackdown and clean-up of New York City’s Washington Square Park and the West Village. Gays were one of the only groups not organized in any way, and they suffered daily from virulent police brutality. One could say Stonewall was their “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore” moment.

This was at the height of many national Civil Rights movements in the United States—on the part of blacks, on the part of women, on the part of every marginalized segment of society that started demanding from their government, whose job it was to hold up the tenets of the nation’s Constitution, to “get off our backs and deliver on the promise” of protecting the rights of every member of its citizenry. Everything started erupting in 1968: that summer in Chicago saw an historical protest outside the Democratic National Convention. 1969 was the year of a mayoral re-election campaign for Republican John Lindsay that brought a major crackdown and clean-up of New York City’s Washington Square Park and the West Village. Gays were one of the only groups not organized in any way, and they suffered daily from virulent police brutality. One could say Stonewall was their “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore” moment.

Since, shockingly, few photos or video footage of the raid and the consequent three nights of the uprising exist, Davis and Heilbroner have used recreations and other archival materials drawn from that time in order to create a robust and powerful document of a barely documented event. The accompanying Greek chorus that emotionally and articulately provides first-hand testimony includes: Seymour Price, Deputy Inspector, Morals Division of the NYPD (retired), who was in charge of a very frightened police force that night; Dick Leitsch, president of the Mattachine Society of New York, the first gay rights organization who fought for the eradication of police entrapment, among other things; Yvonne Ritter, who was celebrating her 18th birthday at the Stonewall Inn the night of the police raid; Martha Shelley, the instigator of the first gay protest march one year after Stonewall, which has now become known as the Gay Pride Parade, celebrated the world over (this year will mark the 40th anniversary of that very first march); Ed Koch, the former mayor of New York City and its Councilman at the time of the uprising; Howard Smith, a Village Voice columnist from 1966 to 1984 (the Voice’s offices were right down the street from the Stonewall and Smith and reporter Lucian Truscott IV would be caught up in the riot, seemingly the only representatives from the press covering the event); and David Carter, the author of the book upon which the film is based (Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution) and who was a key consultant to the filmmakers.

Flawlessly edited by Davis, with a graceful and economical script by Heilbroner, Stonewall Uprising illustrates another great step forward in the story of human rights. Remember that when you march this year. And remember to pay respect to those men and women who came right before you, for they are the ones who made the freedom to be “out and proud” possible.

— Pamela Cohn

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail