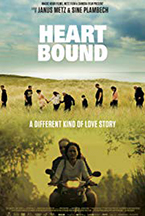

A Conversation with Janus Metz and Sine Plambech (HEARTBOUND)

I met with directors – and spousal partners – Janus Metz and Sine Plambech on Sunday, September 9, 2018, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss their new feature documentary Heartbound (which I also reviewed). The movie offers a moving portrait of the women and men, the latter Thai and the former Danish, who marry and forge new lives together in the north of Denmark, mostly thanks to the efforts of one very strong-willed woman, Sommai. She married her own Danish husband over 20 years prior, and has since worked tirelessly to help out her fellow compatriots as they seek financial opportunities beyond those offered in Pattaya, the nation’s sex-tourism capital. It’s a complex story, and the directors do it ample justice. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I met with directors – and spousal partners – Janus Metz and Sine Plambech on Sunday, September 9, 2018, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss their new feature documentary Heartbound (which I also reviewed). The movie offers a moving portrait of the women and men, the latter Thai and the former Danish, who marry and forge new lives together in the north of Denmark, mostly thanks to the efforts of one very strong-willed woman, Sommai. She married her own Danish husband over 20 years prior, and has since worked tirelessly to help out her fellow compatriots as they seek financial opportunities beyond those offered in Pattaya, the nation’s sex-tourism capital. It’s a complex story, and the directors do it ample justice. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: I understand that the film took approximately 10 years to make, according to the press notes and the title card of the film. Also, it’s based on Sine’s research, because you’re an anthropologist, correct?

Sine Plambech: Yes.

HtN: So, let’s start there. How did you come across the subject and then decide to make a film about it?

SP: I started working among this group of Thai women 15 years ago, in a small, remote island in Denmark, and I thought it was just an interesting question from a research perspective. Why are there so many Thai women in this remote area? What are they doing here? Where are they coming from? And what kind of relationship is it that they have with these Danish men that they are living with? And so, I spent three years with them, on and off, interviewing and doing my anthropology, and then Janus and I met, and Janus was interested in portraying this type of migration. We started our conversation, and that’s 10 years ago.

HtN: So, you had not yet met Janus when you first started working on this. It was just you?

SP: It was, at first, just me, yes, for 3 years. I gathered information, and also the trust of the women in the film. I went to Thailand, to the village where most of them are coming from, in our film. I built that structure prior to our work together.

HtN: So, Janus, you met Sine and then when did you start thinking, “This would be a good subject for me to invest in as a filmmaker?”

Janus Metz: Well, right away, because I was …Sine showed me some photos from this Thai village of houses, houses of women that had migrated to Denmark and houses of families where there was no one that had migrated, and the migrant families lived in huge – by Thai village standards – almost mansions. And the other families lived in traditional little wooden shacks. So, I thought, just the sheer image of difference was interesting, from a visual perspective. And I’ve always been interested in stories of globalization and trying to place Denmark on the global scene, to give people a perspective on who they are at this time and age right now, right here. And maybe shape their understanding of other people that come from other places.

So, I thought this was an interesting story. Where they lived was a very, very cinematic place in Denmark, which is very…I mean, now we’re in Canada so here you really get vast open spaces…but by Danish standards, vast open spaces and lonely farmhouses and violent seas. So, this whole story of longing and loneliness and survival and needs across a global divide, and the people that are part of this, just captured me.

HtN: How do you pronounce the province in which your subjects live? T-H-Y…how do you pronounce that in Danish?

SP: [something that sounds like] “Tieue” [or “Chiu”]

HtN: “Tieue”

JM: Mm-hmm.

HtN: Got it. There’s a nice visual resonance between Thai and Thy, the way it’s written, but it’s pronounced differently. Is Denmark a special case in terms of percentage of Thai women per capita? Did you find that in your research, or did you look at how it compares to other countries? One of the characters, of course, marries a Finnish man, but I’m just curious if there’s something that draws people, either Danish men to marry Thai women or Thai women to Danish men, in particular. Or is it comparable to other countries?

SP: No, actually, what’s interesting is that Denmark is not unusual in that sense. It’s more a global dynamic or at least a Western European dynamic, so there are many of these kind of marriages across Germany, Sweden, Norway. What’s interesting now is that Thai women are now the nationality that Danish men most often marry, besides Danish women, and that’s specific to Denmark, that percentage. But we see in many areas in Scandinavia and Western Europe, in rural communities, that Thai women are marrying Western European men, in northern Norway, northern Sweden, in the countryside in Germany. So, in that way, our film just shows a small corner of a more global dynamic.

Our Chris Reed and filmmakers Sine Plambech and Janus Metz

HtN: Sure. I always say that out of great specificity come universal truths. So, OK, it’s not unique to Denmark. But it is interesting that you find that Danish men do marry Thai women in, you say, larger percentages than they do other nationalities. Is it the single largest foreign group they marry?

SP: It’s the single largest nationality that Danish men marry besides Danish women.

HtN: Why do you think that is?

SP: I think there are many dynamics to that. Our film is about the men who are in this remote area and who previously were married to Danish women, and now in their late age they’re looking for love elsewhere. In recent years, it’s also many young men who are traveling to Thailand and working there, so we see another group of Thai women who are entering Denmark. But it’s also a question of the dynamics of loneliness and questions about masculinity and femininity in Western society. What is it that we want for our families, and what kind of women is it that these men are longing for, along with family values and traditions? Sometimes they have ideas that what they will, so to speak, get from a Thai woman is a more traditional kind of family-oriented woman. And what we really show in our film is that it’s kind of more complicated than that. Of course, you cannot just buy someone, buy that idea. It’s not what’s really going on.

HtN: Of course, yes. They’re not robots.

SP: No.

HtN: And what I love about the film is how you take this idea that we perhaps have preconceived notions about, and then you show the real, true complexity beneath it. In some ways I could potentially imagine some of the men being reluctant to be on camera to talk about this, but everyone, men and women, seem so comfortable in front of the camera. What were some of your challenges, Janus, getting people to agree to be part of the film, if any?

JM: I think – I mean you say yourself – there’s a lot of prejudice around these kinds of relationships: the men are perverts, the women are gold diggers or sex workers, or they’re sex slaves to some extent. And I think they were genuinely interested to tell people about their lives, to break down some of these stereotypes, and I think we have quite easygoing, trustworthy personalities. And great persuasive gifts. (laughs) No, that was a … We were able to gain their trust, not least because of Sine’s research, that we took them seriously.

We were not there to point fingers. We were there because we all share a need for love, we all share a need to provide for our children. What you guys do are not so different from what we do. You might find other ways and other venues, but people take the choices they take from where they stand. So, I think if you can transport yourself into the life of a Thai woman that has few choices – you can be a day laborer, you can be a sex worker, you can be a marriage migrant – and try to understand why does she take the choices that she takes, and how can the idea of a marriage with a total stranger and leaving…with the consequences you’d have to leave your kids behind…be a necessary choice? And sometimes even a better choice than other choices.

HtN: And I think your film does an excellent job of pointing that out, if anyone did have judgements of the women. I think you make it very clear how limited the choices are, and how even so, it’s not an easy thing for some of them to enter into. I like that term, “marriage migrant,” much more than “mail-order bride.” It’s a great term. I hadn’t heard it before.

SP: I never call them mail-order brides. Also, because they’re not ordered by…

HtN: But that’s the sort of general umbrella term…

SP: It is, yes. But I really think it actually speaks to the idea that they are ordered or that they don’t have any choice in what they’re doing, and that they’re just kind of coming down by mail. So, I think that term actually speaks to a problem which is larger, which is this perspective of them as not someone having agency, having choice, and on this limited scale, trying to make decisions about their own lives.

A still from HEARTBOUND

HtN: Which, again, I think you explore very well. I do find interesting how relaxed and comfortable in some way [subject] Niels was in explaining how he and [his wife] Sommai met, since that’s an area that perhaps would be subject to more critical judgment given that he was on a sex tour. So, from the male perspective, that’s why I imagine some of the men might have had more issues than …

JM: I can talk a little more about the men because this film often becomes about the women. I think Niels is a wonderful guy because he’s also a provocateur in some ways: “What you might think is the way that you live your life, well, I took the choices I took because I had to take those choices. I was lonely, I hadn’t been with a woman for eight years, my wife left me, what can I do? Do you want me to commit a slow suicide by sitting on my couch watching television?” What I like about the men is just as the women try to survive and get out of poverty, the men are also struggling to survive. Loneliness can kill you. And they’re desperately trying to seize life and to feel a sense of self-worth and feel a sense of importance and feel that they have someone to care for.

Niels went to Thailand on a holiday and was…He blatantly admitted that he was a sex tourist, and he fell in love with Sommai. There are films made about this. It’s a Pretty Woman type of story, if you want to be a little banal about it. The real-life Pretty Woman. And he stands by that, and he stands by her. So, I think it’s also about dignity. If people morally condemn your choices as shameful, regaining dignity is also standing by what you did from a human perspective. And I think that’s what Niels does when he says that.

HtN: And out of it, however one feels about it, came this amazing relationship with Sommai, who has done so much. And I love, actually, the range of types of marriages that you show. Mong and John, who seem to genuinely like each other and have a good marriage, versus some of the other more…perhaps less so. It runs the whole gamut, and I find that quite fascinating.

So, Janus, you have gone back and forth in terms of documentary filmmaking and fiction filmmaking. I’m just wondering how you might see them as a director, approaching them differently. Most recently, you did Borg vs McEnroe. How is it, jumping back and forth? You’re not the only director to do this, but is there one genre in which you feel much more comfortable?

JM: No, I think they’re mutually inspiring, and they give so much to each other. I think filmmaking is filmmaking to me, and the more films I make, the less of a difference I think there is between documentary and fiction. I wouldn’t even call it genres, because a genre to me is a thriller, or a comedy, or something. I would say it’s methodologies of filmmaking, and the goal is always the same: it’s to try and create life and to tell important stories. So, whether you find that in the form of a documentary or you find that in the form of a fiction film, it doesn’t really matter to me. It’s what serves the purpose best. I can say…one of the things that comes up is…fiction films tend to be shorter and more condensed, in the time that it takes to make them. It’s a sprint.

HtN: And certainly more planned and organized.

JM: Yeah, until it all explodes and becomes very chaotic, anyway. Because the one thing you can say about filmmaking, it is never going to be as organized as some people try to tell you.

HtN: Sure.

JM: But now we’ve made a documentary, and it took 10 years to make it, and it’s certainly something that you have to consider also, just from a life perspective. What kind of life do you want to live? Documentary filmmaking is tough, in that sense.

HtN: Well, I love the film. Congratulations on making it. I hope it does great things for you and for everyone involved.

JM: Thank you so much.

SP: Thank you so much.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)