A Conversation With Gillian Armstrong (THE PEOPLE HE’S UNDRESSED)

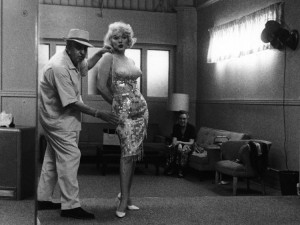

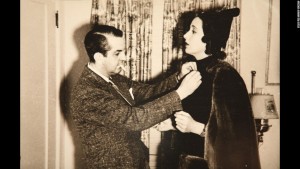

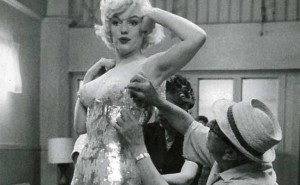

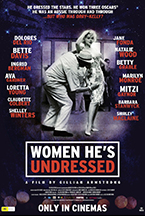

I recently spoke by phone with director Gillian Armstrong (My Brilliant Career, Mrs. Soffel, The Last Days of Chez Nous) about her new documentary feature, Women He’s Undressed, (which I also reviewed here) which tells the story of Australian-born Hollywood costume designer Orry-Kelly (born Orry Kelly, without the hyphen), winner of three Oscars (for An American in Paris, Les Girls and Some Like It Hot) and the man responsible Bette Davis’s on-screen style throughout the 1930s. Other films he designed include Casablanca, Oklahoma! and Auntie Mame. Here is a condensed digest of that conversation, edited for clarity.

I recently spoke by phone with director Gillian Armstrong (My Brilliant Career, Mrs. Soffel, The Last Days of Chez Nous) about her new documentary feature, Women He’s Undressed, (which I also reviewed here) which tells the story of Australian-born Hollywood costume designer Orry-Kelly (born Orry Kelly, without the hyphen), winner of three Oscars (for An American in Paris, Les Girls and Some Like It Hot) and the man responsible Bette Davis’s on-screen style throughout the 1930s. Other films he designed include Casablanca, Oklahoma! and Auntie Mame. Here is a condensed digest of that conversation, edited for clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So producer Damien Parer approached you with a proposal for a film entitled Gowns by Orry-Kelly in June, 2012. What was your reaction?

Gillian Armstrong: I said, who is Orry-Kelly, I am ashamed to admit. I had never heard of him. (laughs) I have since made up for that!

HtN: I would say you have! So you had never heard of Orry-Kelly before the film was pitched to you. Could you describe your research process? Or, to quote you, yourself, back to you, from your official filmmaker statement on the movie, “How do you tell a story about the life and work and art of someone when they are gone when there are very few left alive who ever knew you?”

GA: It was a challenge. I mean, obviously, as soon as I looked at Orry’s credits, I went, oh my God, I know all of these amazing films. I can’t believe that an Australian from a small country town ended up as one of the top costume designers in Hollywood! So the first thing I asked was, how did he do that? And…well, let’s go back to the beginning.

So we went to [his hometown] Kiama, and they have a little historical society with a very passionate historian, who had that photo [used in the film] of a very young Orry. She knew who Orry-Kelly was – a hero from their town! – and they also had a medal from his father, who was also a hero in the town, as he had swum out to save people in a sinking ship. She gave us background on what life was like there in the 1890s. She knew that Orry’s mother had been a big fan of his, and she had some saved local articles where his mother had talked about how talented her son was.

And then we went to Wikipedia, and when you go to Wikipedia, the big thing that comes up is about how Cary Grant was Orry’s lover, and then there were a lot of other things that were questionable, where I thought, well, we’ve got to find out whether this is true: whether the Cary thing is true; whether it’s true that he was hated because he had tantrums; whether he was named after a carnation – and as it turned out, the carnation was named after him!

The other thing we did was to contact the costume historians, and we got on to Deborah Nadoolman Landis and David Chierichetti quite early on, because they’ve both written substantial books about the history of costume design and have mentioned Orry. We’d heard…there was this rumor that he’d written his memoir, that there was this missing manuscript and that costume historians had been trying to find it for years. So that became, for Katherine Thomson – the writer – and I, like our quest. If only we could find it, we could hear what he really thought, behind the scenes, about the actors, and maybe what he thought about Cary. And we literally started a search, which took us about two years, and we had actually given up, when we found it, in the end, in a completely random moment.

HtN: And at the end of the film, you present, to the audience, the discovery of Orry-Kelly’s memoir, but you also still kind of shroud its contents in mystery. Did you, yourself, read it, and is that what fueled most of the research that we see on screen?

GA: Well, we nearly made the movie without it, but when we read it, we said, we got him right. So that was fantastic. There were bits [of dialogue in the reenactments] where we took little liberties, but the scene, for instance, where Cary came to him, and Orry thought that he was going to patch up the friendship, is completely from the memoir. And the little quote where he says, “and I saw Dark Victory on TV last night, and it stood up quite well,” was also a direct quote. So there were definitely little pieces that we took from the memoir that were real things that Orry said. Others came from the letters, while here and there was a little bit of what my writer felt would be the sort of thing that he would say. It’s such a mix now, we don’t even remember, did we make that line up or was that really Orry…

HtN: So speaking of research and Cary Grant, I am by no means a Cary Grant aficionado, although he happens to be one of my favorite actors of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Before watching your film, I had always assumed that the stories of his alleged homosexuality, or bisexuality, were unconfirmed, although I had heard about his relationship with Randolph Scott. Your film, however, makes the case, very strongly, that he was gay…

GA: Well, I think he probably was bisexual. I think that Randolph Scott was probably the love of his life, and he and Orry lived in an apartment in New York for 9 years. I asked Eric Sherman, who is [Hollywood director] Vincent Sherman’s son…and Vincent took over the apartment when Orry and Cary were running from the mafia, which is all true, because they ran a speakeasy and got in debt…and I said to Eric, how many bedrooms were there in the apartment, and he said there was only one. The person who could really tell you the truth is [Hollywood fixer] Scotty Bowers, and Orry is mentioned in Scotty’s book [Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Live of the Stars], and when we talked to Scotty, he was like, “YES, I spoke with Randolph…”

In the end, for me, it’s not about some sort of thrill-seeking, finger-pointing thing about someone’s sexuality. For me, what I hope comes through is that there was such pressure on everyone in Hollywood, during the time of the [Production] Code. And if you were a leading man – a heterosexual leading man – you had to have an image. And I think it was very sad that people couldn’t live their life freely, not that I’m denying in any way that Cary may have loved many of his wives along the way, but there was definitely a lot of pressure on gay actors…and, I think, on gay costume designers!

HtN: Right, and your film makes that pressure very clear. I’m just curious if you’ve gotten any kind of pushback from Grant’s estate or his daughter [Jennifer Grant], because her book [Good Stuff: A Reminiscence of My Father, Cary Grant] about her father treats those stories as rumor.

GA: When we first went online, everything is up there, and there are all these denials from his daughter, so I just decided that this film is not about, “Was Cary Grant gay or not?” I mean, for me, this story is about how Cary figured in Orry’s life, and also about their friendship. So we didn’t approach them, because there was no point: I wasn’t doing a discussion about was he or wasn’t he, which I do think is pretty puerile. And you know what, if my daughter, in another 10 years after I’m gone writes a book about my sex life, excuse me, she has no idea! (laughs)

HtN: (laughs) That’s right!

GA: I mean, what are your kids going to say? And in the end, who cares? I’ve got so many gay friends, who cares? Who cares what you do in bed? As long as you’re not hurting anybody…William Mann tells a story in his book [Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood, 1910-1969] – which is not in the film, because again, this is not about Cary – about how a maître d’ spotted two elderly, white-haired men, holding hands under the table in a posh Beverly Hills restaurant, and it was Cary Grant and Randolph Scott. And I just think that is a very, very sad image, that there are two people who had maybe always loved each other and they were not allowed to live together, and I have a lot of compassion for them.

HtN: And I think that comes through. So let’s leave Cary aside. Could you talk about your aesthetic decisions as far as the reenactments go, namely your choice to film those reenactments of Orry-Kelly’s youth using the metaphor of the boy in the sailor suit, rowing?

GA: Sure. The big issue was that we obviously didn’t have a lot of footage of Orry, because no one films the costume designer, and we didn’t have that many stills. And a key part of his character was his self-deprecating humor, and we just thought, in the end, that if you just had a talking head discussing him, you might want to actually hear Orry, himself. We had a lot of the funny things that he said, from his letters to George Cukor and so on. And we thought, you want to hear them, so you get the sense of the man. Also, I wanted to get an inner arc of the story: we wanted his emotional journey. We wanted his reaction…we could imagine what his reaction was, for instance, when he finally got his award, but his mother was no longer alive. Or his feelings about Cary leaving him, when they’d really been such good friends in the beginning. So we decided that we would put those words in an actor’s mouth.

Now, I hate the on-the-nose reenactments that you often see in a documentary, where someone’s telling you something, and you actually see it on screen: someone saying, “and then, he went down the road,” and you see someone walking down the road. So I wanted to stylize them. And we needed a visual link, because we knew that in the end, we were going to have such a mix of footage: talking heads, clips from the films, his designs, and so on. So I wanted something that was thematic and also had a lot of color in it, as a link, because we knew we were starting off with a lot of black and white but were going to end in the 1960s, when his designs were so vibrant. From that, we came up with the obvious idea, because we had that photo of him as a little boy, in that prop boat – because Kiama was like a seaside holiday town – and so we took that idea of the boy in the boat and put a man in a boat. And as it turned out, the old wooden boat that we hired was red and blue, and this was such a low-budget film that my designer and I said, why don’t we just take this boat as it is? We don’t have to re-paint it; it has such great color. And then we came up with the idea of doing all of those projections to change the mood, and going with the theatrical look. And I know that some people go with it, and some people find that it’s an odd thing in a documentary. As it was about art and design, I felt that we were allowed to go for it.

HtN: Well, I definitely went with it. Last question. In your career, you have made both documentaries and fiction films, but the balance is slightly in favor of fiction. I spoke to Werner Herzog in June about this same thing, and he said that it is easier for him to get funding for documentaries than narratives, which is why he has made more docs, lately. Do you concur that it is just easier to get funding for those?

GA: It is, and you don’t need as much money, and you also have so much more creative freedom. Especially with fewer and fewer more complicated human dramas being funded in the last 10 years, with everything being turned into big tentpole cartoons, which is not my thing. But I love making films, so I’ve had fun doing these little art documentaries (laughs) it still took three years to make!…and I love the creative freedom to do these crazy things like have a man in a red boat with projections on him and so on. So creative freedom and the relative ease of raising money is why I’ve done documentaries, whereas, for a lot of my dramas, studios just haven’t been backing complicated adult dramas. They’ve all gone to TV! I mean, American TV dramas right now are amazing. And all the good writers have gone there, so … you may see me in that area. We’ll see…

HtN: Let’s hope! Well, thank you for your time. I really enjoyed your film, and I enjoyed talking to you.

GA: Oh, good! And I’m glad you liked my man in a red boat.

HtN: (laughs) I did. Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)