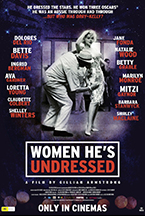

WOMEN HE’S UNDRESSED

(Accomplished director Gillian Armstrong brings the story of classic Hollywood wardrobe legend Orry-Kelly to the screen in her well done and eye-opening documentary Women He’s Undressed. The film is playing now in L.A. and opens across all digital platforms August 9, 2016 via Wolfe On-Demand.)

For those who like their documentaries without conspicuous directorial mise-en-scène, Women He’s Undressed may not be for you. For quite some time, however, we have been in an era where the aesthetic of cinéma vérité has long been abandoned by many in favor of a greater variety of styles and storytelling devices. The “truth” of documentary filmmaking has always been a construct, anyway, since the very first movies by Auguste and Louis Lumière, in 1895, where they asked the workers in their factory to repeat an action three times for three different versions of their famous Sortie des usines. From Robert Flaherty’s highly manufactured not-so-real-life first feature Nanook of the North, in 1922, to experimental works like Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, in 1929, to wartime propaganda films like Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series, in the 1940s, and beyond, documentaries used a combination of fiction and non-fiction elements to portray the truth as the director saw it. It was only in the 1960s, with the rise of “direct cinema,” that we really started to develop this idea of aesthetic purity in the documentary genre. If one believes (and one should) that the very act of framing an image, and then cutting out parts of it in the editing process, constitutes directorial manipulation, then one realizes that purity and truth are relative. A movie is a movie is a movie, and should stand on its own as a work of art.

Facts, however, are not so relative, and the beauty of Women He’s Undressed is that it feels grounded in actual research. From Australian director Gillian Armstrong – who has made both independent narrative features (My Brilliant Career, Oscar and Lucinda) and Hollywood studio films (Mrs. Soffel, Little Women), as well as documentaries (Bingo, Bridesmaids & Braces, Love, Lust & Lies) – comes this fascinating look back at the life of the once-renowned three-time-Oscar-winning costume designer, Orry-Kelly. Born in 1897 as Orry Kelly (without the hyphen), in Kiama, a small seaside town on the southwest coast of Australia, 75 miles below Sydney, Kelly first made his way to that big city before moving to New York in 1922 and then eventually heading to Los Angeles in 1931, where he quickly established himself as a brilliant “hem-stitcher” (as he called himself). Before long, he had become Bette Davis’s main designer, and then went on to make the costumes for such enduring classics as Casablanca, Arsenic and Old Lace, An American in Paris (Oscar #1), Les Girls (Oscar #2) and Some Like It Hot (Oscar #3), among so many others. Looking purely at the list of his credits on the film site IMDb, one feels a sense of awe at the breadth of his accomplishments.

The film is about much more than his work, however. An openly gay man, he found that the life that he had lived with such ease in New York was not so acceptable as Hollywood grew more conservative with the rise of the Production Code in the 1930s. His lover/roommate in his Greenwich Village days, Archie Leach, who followed him to the West Coast, felt forced to adapt to the new ways as his acting star rose and his name was changed to Cary Grant (yes, that Cary Grant, speaking of constructs), abandoning his new love, Randolph Scott, for a series of ill-fated marriages to women. Abandon your preconceived notions of the great actor (one of my personal favorites), and accept that the facts you think you know may be as fictional as his name. But Kelly, himself, remained true to his inclinations, though he was ever discrete (until a bad drinking habit caused him some professional distress later in life). The story told here is as much about the age-old societal pressure to conform as it is about the life of one exceptional small-town-boy-made-good. As in the best of tales, out of great specificity emerge universal truths.

Which brings us back to Armstrong’s methods. Her movie is filled with an array of wonderful talking-head interviews from costume designers who knew Kelly and those who admire him now, film historians, and even Jane Fonda, who as a young ingénue worked with Kelly as her career was starting and his was ending (on films like The Chapman Report and Sunday in New York). What makes Women He’s Undressed exceptional, however, is not Armstrong’s use of the usual bag of tricks for historical biographies, but rather her highly stylized reenactments. Inspired by a childhood photograph of boy Orry in a boat, she has filmed a series of interludes where an actor incarnates Kelly as he sits in that boat, rows against the storm of life, and recites lines from his letters and heretofore-unpublished memoir. It’s a wonderful device, especially since there is almost no footage of the real man (who films the costume designer?), and it anchors the story in the delightful essence of Kelly’s personality, raising the movie high above a mundane recitation of facts. As a result, what we get is a film to be savored by aficionados of Hollywood and lovers of cinema, alike.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)