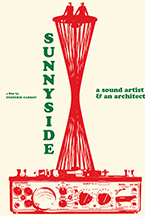

SUNNYSIDE

(The 24th Annual Slamdance Film Festival ran January 19-25 in Park City, UT. Hammer to Nail has you covered and guarantees more coverage than any other site. Watch us work it!)

If you like observational documentaries, with no exposition or interviews to explain the story, you’ll love Sunnyside. It’s a portrait of two old friends, both now deceased, who lived for many years on the same hillside in Marin County, California. The directorial debut of Belgian filmmaker Frederik Carbon, the film offers a poignant exploration of life at its conclusion, focusing on sound artist Henry “Sandy” Jacobs (1924-2015) and architect Daniel Liebermann (1930-2015). Both men are still active, mentally and physically, when we begin. Though older, Jacobs looks and acts younger; Liebermann’s more frail state belies a sharp acuity of the mind, however. We never learn what originally brought them to the neighborhood – nor how they met – but together, in their separate houses, they form a pleasant pair, and make for very compelling cinematic subjects.

Carbon jumps right in with Jacobs, whose pioneering work with reel-to-reel-tape audio montages, dating from the 1950s and 1960s, is played throughout and forms what nondiegetic soundtrack there is. His is the impish spirit of the movie, whether he is teasing Liebermann – his downhill neighbor – skinny dipping in his makeshift hot tub (a large wooden barrel), or commenting irreverently on his past achievements. Architect Liebermann is the more serious of the two, though not above a humorous story or two, such as when he recounts – complete with drawings done on the spot – the time that Jacobs’ barrel collapsed, sending him sliding down the hill, naked. Unlike his carefree uphill neighbor, however, Liebermann still has real-world concerns that intrude on his idyll of retirement, such as when he receives a citation and fine for a building commission gone awry.

Joining them regularly in the frame is Lia, a young woman – origins mysterious – to whom Liebermann offers shelter in exchange for work and maintenance on his house. Another woman – closer to their age – appears one time with Jacobs in his barrel. We learn from the end credits that this must be Susan Hyde, his longtime romantic partner, though we never see her again. Workers in the background come and go, but only the film’s subjects are ever truly foregrounded. There’s a dreamlike quality to the affair, with many cutaways to the surrounding trees, the distant Pacific Ocean, and the rain and wind that occasionally arrive. At only 72 minutes, the film’s opacity never grows tiring. Instead, the lack of concrete, explicit details increases our interest.

Carbon edits in some archival material, however, though sparingly. One of my favorite such moments comes early on, after Jacobs has walked Carbon down to Liebermann’s house, and we then cut to a similar walk and entrance from years earlier. We also see a much more physically vibrant Liebermann from the mid-1990s, cleaning up the devastation from a brutal forest fire. It’s just enough to give us a sense of the passing of time, and the continuity of their life in Sunnyside. Theirs was long a love-hate relationship, but a meaningful friendship, nonetheless, and when the movie closes on their respective ends, we know we’ll miss them dearly.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)