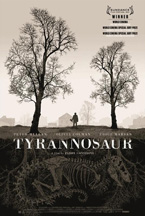

(Tyrannosaur is now available on DVD. It world premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival and was subsequently picked up for distribution by Strand Releasing.)

Tyrannosaur is violent in every sense of the word. Fights break out, windows are smashed, emotions seethe. Writer-director Paddy Considine (better known as an actor from such films as In America and the Red Riding trilogy) wastes no time in establishing that his film could erupt at any moment, making it tense even at its most seemingly placid. What makes watching this barrage of aggression more compelling than it might otherwise be is the fact that nearly every act of violence stems from a desperate attempt not to turn the rage inward—especially for Joseph, our troubled protagonist. Violence seems to be his first impulse from the moment we meet him (so much so, in fact, that it inspired seven walkouts within the first ten minutes of the film’s screening at the Nantucket Film Festival) and indeed it seems to be the only way this stunted individual knows how to express himself. He has few loved ones who aren’t dead or on their way out and spends most of his time not spent brawling on other, more productive activities, like getting drunk. Though Tyrannosaur’s attention-grabbing title technically refers to Joseph’s deceased wife, it’s through him that it takes on a meaningful shape: it evokes power, to be sure, but also a certain helplessness. This is a film about inner turbulence masked by outer strength.

Instead of short, ineffectual arms, Joseph’s weakness is an internal strife that manifests itself via outward acts of fury. He’s a severely damaged person, and it’s by a mix of happenstance and a subconscious decision that he happens upon a kindred spirit in the repressed, alcoholic, and deeply unhappy Hannah. The two appear to be nothing alike at first—she’s mousy and religious where he’s aggressive and vulgar—but the circumstances relating to their woe aren’t entirely dissimilar. It’s almost entirely on the strength of Peter Mullan and and especially Olivia Colman’s excellent performances that Tyrannosaur transcends its admittedly contrived premise with such ease. They’re tender and sympathetic in their portrayal of two lost souls oscillating between arm’s length and total intimacy, always with a certain amount of tension and reticence, and the ways in which Hannah is even more battered an individual than Joseph are at times shocking. Considine is as concerned with the slow process of recovery as he is with the wounds that need healing, whether they show themselves on the body or not.

Instead of short, ineffectual arms, Joseph’s weakness is an internal strife that manifests itself via outward acts of fury. He’s a severely damaged person, and it’s by a mix of happenstance and a subconscious decision that he happens upon a kindred spirit in the repressed, alcoholic, and deeply unhappy Hannah. The two appear to be nothing alike at first—she’s mousy and religious where he’s aggressive and vulgar—but the circumstances relating to their woe aren’t entirely dissimilar. It’s almost entirely on the strength of Peter Mullan and and especially Olivia Colman’s excellent performances that Tyrannosaur transcends its admittedly contrived premise with such ease. They’re tender and sympathetic in their portrayal of two lost souls oscillating between arm’s length and total intimacy, always with a certain amount of tension and reticence, and the ways in which Hannah is even more battered an individual than Joseph are at times shocking. Considine is as concerned with the slow process of recovery as he is with the wounds that need healing, whether they show themselves on the body or not.

That an attack dog (a pit bull, to be precise) features as prominently as it does is telling. The canine in question lives across the way from Joseph and, whether through simply barking too loudly or posing a threat to the young boy with whom Joseph has a kinship, frequently irks its rage-inclined neighbor. “It’s not your fault,” Joseph says aloud while pacing through his house, wielding a club, and trying to restrain himself from lashing out at the dog; he understands that it isn’t dangerous to any inherent malevolence but because it’s a product of its environment. But he also knows the moment it snaps could come at any second. In other words, he sees himself in the creature. That Joseph is easiest to understand in relation to a chained dog and a prehistoric beast likely gives one a strong sense of the divide between him and his fellow humans, but the humanity behind his primal aggression comes as a surprise. Far and away the best film I saw at Nantucket, Tyrannosaur isn’t perfect, but neither is it meant to be: its flaws and anger reflect that of its characters. But, like them, it’s worth looking past the scarred surface to the more beatific qualities below.

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail