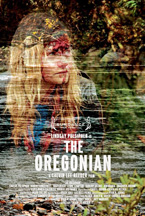

OREGONIAN, THE

(The Oregonian world premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival. Factory 25 is releasing the film on home video and is now taking pre-orders on a Limited Edition DVD—click on that link to see just how cool of a package it actually is. It is being distributed theatrically by Cinemad Presents and opens in NYC at the reRun Gastropub on Friday, June 8, 2012. It is also currently available for streaming on Netflix and Hulu. Wherever and however you track it down, just be sure to watch it as loud as possible! NOTE: This review was first posted on Thursday, June 7, 2012, as a Pick of the Week at the Filmmaker Magazine blog.)

Calvin Lee Reeder’s The Oregonian is a horrifying film, if not what is commonly perceived as a “horror” film. It is deeply and fundamentally upsetting in an off-putting way that will sicken and alarm you if your idea of pure terror is anxiety over your own mortality and meaninglessness or being alone and lost in an unforgiving environment, as opposed to the tired slasher movie shock tactics of a knife appearing behind a scantily clad character to the tune of a sudden musical cue. Its closest comparison might very well be that other recent dreadful paean to social miscreants and the human-disguised demons that live among us (not to mention a celebration of outdated film/video formats): Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers. Rather than setting out to surprise and astonish you with allegedly clever cuts and reveals, both films instead understand the value in establishing a truly sickening atmosphere of discomfort and misery, leaving the viewer unable to escape the insular world meticulously created by a clever conglomerate of every tool in the filmmaker’s arsenal. In The Oregonian, it all begins with the shooting format—mostly scratched, likely expired 16mm celluloid—before expanding to the bleak yet lush and familiar landscapes familiar to so many horror movies, and culminating with an aural assault of sound effects, music and breathing that suggests a panic attack happening inside an experimental folk music performance.

The Oregonian succeeds largely due to Reeder’s specificity of what constitutes unpleasantness, a uniquely unsettling examination of revolting fluids and substances that appear and spew forth in inhuman quantities. Think blood, oil, boils and vomit interspersed with references to eggs and breakfast and you will want to cover your eyes not out of fear for what may happen next, but to prevent yourself from gagging at the sight of the expulsions splattering the screen.

The Oregonian succeeds largely due to Reeder’s specificity of what constitutes unpleasantness, a uniquely unsettling examination of revolting fluids and substances that appear and spew forth in inhuman quantities. Think blood, oil, boils and vomit interspersed with references to eggs and breakfast and you will want to cover your eyes not out of fear for what may happen next, but to prevent yourself from gagging at the sight of the expulsions splattering the screen.

Aside from a revolving door of one-scene supporting monsters and monstrous humans (including indie-freakout MVP Robert Longstreet), The Oregonian is mostly a one-woman show for Lindsay Pulsipher, whose performance almost defies categorization as it exists mostly on a level of frenzy and madness that usually only occurs in the final reel of a typical horror movie. Reeder and Pulsipher open their film with a subversion of the “final girl” trope, starting where something like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre ends, with the bloody, damaged and scared-for-life heroine wandering down some anonymous road. In doing so, we provide our own back-story to the events that normally lead up to such a moment. Reeder uses that as a mere jumping off point to explore the unfamiliar territory of the psychological damage and unending trauma that must occur after the credits usually roll.

In taking this approach, The Oregonian announces its awareness of cinema history, genre tropes and audience expectations, but it never stops at alluding to or delivering on them. Thus it is early in the film that the probably-intentional Lynchian industrial imagery, or the sight of a silent stranger who stares with a deranged expression of indifferent exuberance, appear. In acknowledging the presence of these familiar signifiers in the audience’s mind and expectations, casually nodding to them before moving away, Reeder is very much embracing the tradition to which his film belongs. However, as the film progresses and a mysterious plush frog-person appears (maybe a tip of the hat to the fuzzy suited horrors of The Shining, but who knows), it seems that instead of progressing down a so-called “lost highway” we are instead being led in circles to a conclusion that suggests (again) a Shining-eqsue Möbius strip. By the time the simultaneously grotesque, maddening and maybe even hopeful conclusion appears on the horizon and The Oregonian herself has wandered deep into the unknown, I found myself thinking of Jack Torrance being told, “You’ve always been the caretaker. I’ve always been here.” The Oregonian ultimately suggests that we never find the abyss; we only wake up to realize we are already there.

In taking this approach, The Oregonian announces its awareness of cinema history, genre tropes and audience expectations, but it never stops at alluding to or delivering on them. Thus it is early in the film that the probably-intentional Lynchian industrial imagery, or the sight of a silent stranger who stares with a deranged expression of indifferent exuberance, appear. In acknowledging the presence of these familiar signifiers in the audience’s mind and expectations, casually nodding to them before moving away, Reeder is very much embracing the tradition to which his film belongs. However, as the film progresses and a mysterious plush frog-person appears (maybe a tip of the hat to the fuzzy suited horrors of The Shining, but who knows), it seems that instead of progressing down a so-called “lost highway” we are instead being led in circles to a conclusion that suggests (again) a Shining-eqsue Möbius strip. By the time the simultaneously grotesque, maddening and maybe even hopeful conclusion appears on the horizon and The Oregonian herself has wandered deep into the unknown, I found myself thinking of Jack Torrance being told, “You’ve always been the caretaker. I’ve always been here.” The Oregonian ultimately suggests that we never find the abyss; we only wake up to realize we are already there.

— Alex Ross Perry