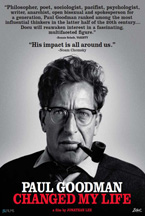

PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE

(Paul Goodman Changed My Life is being distributed by Zeitgeist Films. It opened theatrically at the Film Forum on Wednesday, October 19, 2011. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

I’ll admit to ignorance: I had never heard of Paul Goodman before watching Jonathan Lee’s new documentary Paul Goodman Changed My Life. He is consistently described as a “public intellectual,” or a “man of letters,” mystifying titles that conjure images of cold stone libraries, tweed coats, and Northeastern snow. In other words, out of the past. Apparently Goodman’s variety, though still elusive, was rather more hip: the New York, mid-century, Jewish intellectual, one whose expansive mind seems to have been nurtured by a bewildering array of influences, desires, grudges, and ideals (it’s not for nothing that he’s name-checked alongside Marshall McLuhan in Annie Hall). I tried to think of a current heir, but what came to mind instead were recent fragments: Occupy Wall Street, shellacked political candidates, a glowing white apple. If the poetic tributes to Steve Jobs are any indication, our modern incarnation is the public entrepreneur, the educated genius dropout, comfortable with commerce, whose revolution will be coded, and global. There are niche gurus, like Jaron Lanier, or pop theorists, like Malcolm Gladwell, but a “public intellectual?” Amidst contributions to the fields of psychotherapy, sociology, and poetry, Goodman and his brother Percival co-authored a book on urban design called Communitas; in our modern world that sounds less like a bestseller than a character description in a Wes Anderson film.

A posthumous documentary presents its own challenges. Zeitgeist’s recent Film Forum success was the lively Bill Cunningham New York, which benefited greatly from the dry wit of the subject himself. Lee’s interpretation of Goodman’s story is a more straight-forward affair, its visuals almost fustily old-fashioned, built of interviews (with close friends, family, and distant admirers), archival footage (mostly television appearances), and photos in slow zoom. Goodman’s poems are read, his praises often sung, and his flaws and difficulties revealed but softened by the passage of time (Goodman died in 1972). Lee’s biography weaves in and out of his story, though the focus is on his contributions to social thought. Goodman co-authored the seminal text on Gestalt Therapy, but his breakout work was a commissioned study on juvenile delinquents titled Growing Up Absurd, which was then embraced by the countercultural left in the 1960s. Though Goodman was a pacifist, and railed against the war in Vietnam, he seemed to reflexively push back on any movement or organization that tried to claim him, and was eventually critical of the youth movement’s turn toward violence and drug use by decade’s end.

Personally, I like a solid contrarian, and Goodman seems to fit the bill. In televised appearances he’s quick but cagey, bemused and amusing. The impression he gives is of an impatient visionary, willing to think and write critically about the imposed structures of our society, and frustrated that others’ thinking is more limited. Among other ideas, he suggested doing away with public education and banning private cars from Manhattan. Equally striking was his very public bisexuality in such a repressive era. Goodman had a wife and three children, but apparently also a demanding libido he satisfied with an array of lovers. A fascinating sequence details his prolific outputs on both fronts, suggesting a link between his refusal to repress himself and his ability to express himself. It is said he would spend the morning writing, the afternoon cruising the streets and docks for willing young men, and then return home for family dinner. No doubt this caused suffering, though Goodman’s wife and daughters seem more rueful than angry. It is up to Goodman to turn his sharp words on himself; his poem Ballade of Difficult Arrangements plaintively asks, “How can you be both here and there?” No answer is given.

Personally, I like a solid contrarian, and Goodman seems to fit the bill. In televised appearances he’s quick but cagey, bemused and amusing. The impression he gives is of an impatient visionary, willing to think and write critically about the imposed structures of our society, and frustrated that others’ thinking is more limited. Among other ideas, he suggested doing away with public education and banning private cars from Manhattan. Equally striking was his very public bisexuality in such a repressive era. Goodman had a wife and three children, but apparently also a demanding libido he satisfied with an array of lovers. A fascinating sequence details his prolific outputs on both fronts, suggesting a link between his refusal to repress himself and his ability to express himself. It is said he would spend the morning writing, the afternoon cruising the streets and docks for willing young men, and then return home for family dinner. No doubt this caused suffering, though Goodman’s wife and daughters seem more rueful than angry. It is up to Goodman to turn his sharp words on himself; his poem Ballade of Difficult Arrangements plaintively asks, “How can you be both here and there?” No answer is given.

What his teasing, complex ideas show is how deeply Paul Goodman was willing to entertain new possibilities for social life, particularly for a vibrant, urban community like New York. Watching this film made me yearn for a city that I don’t recognize. I know it’s corny, but I always wanted to be invited to one of those New York parties where there was discussion. I had a vision of men with beards and afros, women in turtlenecks and plaid skirts, where we’d drink red wine and argue about big ideas late into the night. I follow Didion’s beacon up countless dingy staircases, but the result is always the same: they have the right hair and earnest glasses, but all they talk about is styling their roommate’s band’s music video, or Cozumel. In the opposing spirit, the ongoing Occupy Wall Street protests are a breath of fresh, earnest, air, and I’m hopeful they represent some sort of turn, however vague, in a new direction. It’s fortuitous that the Film Forum is showing Paul Goodman now, as a new movement seems to be emerging. Perhaps we have finally caught up with Goodman and his wide-ranging, prophetic, anarchic ideas.

— Susanna Locascio