New York Film Festival 2018 Report: THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND

(The Other Side of the Wind screened at the New York Film Festival on September 29 and October 10, 2018. The film will premiere on Netflix on November 2, accompanied by limited theatrical screenings.)

(The Other Side of the Wind screened at the New York Film Festival on September 29 and October 10, 2018. The film will premiere on Netflix on November 2, accompanied by limited theatrical screenings.)

This review contains spoilers.

The 2018 New York Film Festival came to a close this past weekend. It was a standout year even for this eminent festival, with strong new films from some of the world’s best directors, including Alfonso Cuarón, Claire Denis, Yorgos Lanthimos, Jafar Panahi, Hong Sang-soo — and Orson Welles, who died in 1985. Welles shot The Other Side of the Wind in pieces between 1970 and 1976, but never finished editing it. He left behind a cut that was about 30 percent complete, plus various assemblies and detailed notes indicating his plans for the rest. Extraordinary, tantalizing fragments from Welles’ edit have appeared in various docs and online clips over the years, but decades of legal and financial challenges made it seem unlikely that the movie would ever be realized according to his wishes, or released in any form. But thanks to the tireless efforts of Welles’ friends and collaborators, the technical skills of a team of post-production wizards, and the deep pockets of Netflix (which footed the bill), here it is: the latest, and almost certainly the last, film de Orson Welles.

It begins inauspiciously. Black and white still photos of a car wreck appear, and then a voiceover: Peter Bogdanovich, in character as former wunderkind director Brooks Otterlake, tells us that his friend and hero, the legendary filmmaker Jake Hannaford, died in a car crash on the night of his 70th-birthday party. The opening is Wellesian in structure, with clear echoes of his 1952 Othello and, of course, Citizen Kane: let’s begin at the end, with the demise or downfall of a great man (or a “Great Man”), and then circle back to learn what led us here. But it couldn’t be less Wellesian in feeling or style — Bogdanovich’s V.O. is all plodding, paint-by-numbers exposition, and the images and editing rhythms are utterly conventional. There’s not a trace of the mystery, intrigue, or bravura showmanship that distinguishes the first few minutes of every other Welles feature.

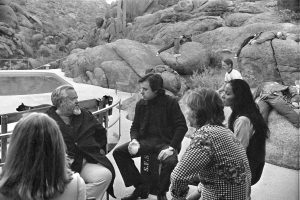

And so the viewer prepares for disappointment, or at least this viewer did. But then, suddenly, the film sparks to life, and we’re hurtled forward into a series of dizzying vignettes, the layers of story unfolding so swiftly that we race to keep up. A group of journalists converges on Hannaford’s birthday celebration, trading rumors about the old man, while a young studio executive, presumably modeled on Robert Evans, screens rushes from Hannaford’s new film-in-progress. Meanwhile, Hannaford (played by John Huston) and Otterlake are interviewed by a film crew; we learn that Otterlake has become Hollywood’s latest golden hit-maker, and his abrupt change in fortune is much on both men’s minds. At the party, Hannaford’s old allies and hangers-on from an earlier time (Huston’s own, and Welles’) mingle with cineastes and scenesters from the ’60s generation. (Dennis Hopper and Paul Mazursky, among many others, make cameo appearances as themselves.) When Hannaford arrives, he screens more footage from his new movie for his guests. The Other Side of the Wind gradually divides into two distinct narrative threads: the birthday celebration, and the extended excerpts from Hannaford’s film.

And so the viewer prepares for disappointment, or at least this viewer did. But then, suddenly, the film sparks to life, and we’re hurtled forward into a series of dizzying vignettes, the layers of story unfolding so swiftly that we race to keep up. A group of journalists converges on Hannaford’s birthday celebration, trading rumors about the old man, while a young studio executive, presumably modeled on Robert Evans, screens rushes from Hannaford’s new film-in-progress. Meanwhile, Hannaford (played by John Huston) and Otterlake are interviewed by a film crew; we learn that Otterlake has become Hollywood’s latest golden hit-maker, and his abrupt change in fortune is much on both men’s minds. At the party, Hannaford’s old allies and hangers-on from an earlier time (Huston’s own, and Welles’) mingle with cineastes and scenesters from the ’60s generation. (Dennis Hopper and Paul Mazursky, among many others, make cameo appearances as themselves.) When Hannaford arrives, he screens more footage from his new movie for his guests. The Other Side of the Wind gradually divides into two distinct narrative threads: the birthday celebration, and the extended excerpts from Hannaford’s film.

In the birthday-party scenes Welles doubles down on the frenzied, kaleidoscopic style he achieved with 1973’s F for Fake. Cinematographer Gary Graver, who also shot F for Fake, alternates rapidly between multiple film formats: Super 8 and 16mm, color and black-and-white. Because so many of the partygoers are journalists and filmmakers, and are seen wielding cameras throughout, the conceit here is that the movie we’re watching is a kind of crowdsourced montage consisting of their footage. Thus Welles anticipates by several years the found-footage subgenre, while outpacing all of its contemporary practitioners in the inventiveness of his editing. The images tumble forward in a rush, and yet for all the variety of filmic textures and the speed of the cutting, there’s nothing imprecise or blurry about the storytelling. It’s a style that’s perfectly suited to capturing the chaotic energy of the party, through which over a dozen supporting characters and dozens more extras surge in and out, scheming, spitting out cynical Wellesian witticisms, angling for attention or advantage. This part of the movie is exhilarating — it shows that Welles was as ahead of his time in the ‘70s as he was with Kane in the ‘40s, and it still feels fresh and innovative in 2018. Younger filmmakers will be studying it and stealing from it for years to come.

Hannaford’s movie-within-the-movie is something else entirely, a full-color 35mm art film consisting of abstract, wordless scenes in which a motorcycle-riding hero (Bob Random) pursues a Native American mystery woman (Oja Kodar) amid a swirl of psychedelic lighting effects, zoom lenses, and comely nude (female) bodies — it feels dated, but perhaps intentionally so, because Welles was clearly imitating then-contemporary styles and techniques. Some critics have taken to calling this part of the movie a send-up of Antonioni, particularly of the Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point era, when the Italian was making films about international youth culture. But the scenes don’t really feel like Antonioni, except in the general sense that they’re supposed to be the work of an older director straining to keep up with the young.

Hannaford’s movie-within-the-movie is something else entirely, a full-color 35mm art film consisting of abstract, wordless scenes in which a motorcycle-riding hero (Bob Random) pursues a Native American mystery woman (Oja Kodar) amid a swirl of psychedelic lighting effects, zoom lenses, and comely nude (female) bodies — it feels dated, but perhaps intentionally so, because Welles was clearly imitating then-contemporary styles and techniques. Some critics have taken to calling this part of the movie a send-up of Antonioni, particularly of the Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point era, when the Italian was making films about international youth culture. But the scenes don’t really feel like Antonioni, except in the general sense that they’re supposed to be the work of an older director straining to keep up with the young.

Which, it turns out, is central to The Other Side of the Wind’s concerns. On one level, the film can be seen as a semi-satirical take on the generation gap in late ’60s Hollywood. “All the old guys are trying to get with it,” says the studio exec watching Hannaford’s rushes, “Is that what this movie’s about?” Well, yes, in part. Hannaford’s career is in decline. He needs funds to finish his film, but the word around town is that the old man has lost the thread and his movie is an unsalvageable mess. Remember that by 1970 Welles had already developed a reputation — unfair though this now seems in retrospect, considering that the triumphs of The Trial and Chimes at Midnight were just behind him and F for Fake just ahead — as a spent creative force, subsisting on past glories. Hollywood paid lip service to his talent, and would still write him checks as an actor, but nobody would give him money to direct. For Welles to make Hannaford’s dilemma central to this movie almost seems like a dare, as if he were teasing us with the idea that Hannaford might be seen as his self-portrait.

In other ways, it’s clear that Hannaford isn’t a stand-in for Welles, or at least no more so than Charles Foster Kane was, or Gregory Arkadin, or Hank Quinlan. Jake Hannaford is the last of the towering Wellesian antiheroes — commanding, charismatic figures who are also studies in corruption and amorality. But Welles had never crafted a character quite like Hannaford before, and some credit for the boldness of the conception probably must go to Oja Kodar. Kodar co-wrote the script with Welles in addition to playing the part of the mystery woman in Hannaford’s movie, and she was Welles’ companion and (along with Gary Graver) key artistic collaborator for the last two decades of his life.

Years earlier, Welles had written a screenplay about an aging macho movie director, a “pseudo-Hemingway” obsessed with a young bullfighter’s bravery and virility. Kodar, meanwhile, had written a story about a director who sleeps with his lead actors’ female companions as a way to displace his repressed desire for the male actors themselves. Welles and Kodar fused the two stories into The Other Side of the Wind. Jake has long hidden his true nature underneath his alpha-male image, but now — is it the permissiveness of the new era? Or old age and the specter of death? — the mask is beginning to slip. His frustrated longings lead him to taunt and humiliate his male lead John Dale (Random, a handsome but blank Canadian), eventually causing Dale to flee the production — heedless, self-destructive behavior on Hannaford’s part, and further evidence of his loss of control.

Hannaford, then, is a fascinating and psychologically complex idea for a character. But he never actually becomes a great character. Huston swaggers through the role, his courtly purring voice barely disguising a fierce will to power, but save for a couple of extended scenes, Hannaford mostly lurks on the sidelines while others talk at length about him. In a celebrated 1950 profile of Huston for Life Magazine, James Agee quotes the director as saying, “On paper, all you can do is say something happened, and if you say it well enough the reader believes you. In pictures, if you do it right, the thing happens, right there on the screen.” The thing is, for too much of The Other Side of the Wind’s running time, the thing does not happen on screen. Jake’s past sexual predilections, his difficult on-set behavior, his troubled family history, his relationship with John Dale — all these and more are described in dialogue rather than directly depicted. When dramatic revelations occur, they usually do so off-camera, or refer to events that took place before the movie began. And what should be the climactic action of the story — Jake’s failed attempt to seduce John Dale, which leads directly to his accident-which-is-really-a-suicide — feels badly muddled, related to us in a wide shot that reveals nothing, with Huston reciting in voiceover what sounds like dialogue written during an all-nighter in the editing room.

Hannaford, then, is a fascinating and psychologically complex idea for a character. But he never actually becomes a great character. Huston swaggers through the role, his courtly purring voice barely disguising a fierce will to power, but save for a couple of extended scenes, Hannaford mostly lurks on the sidelines while others talk at length about him. In a celebrated 1950 profile of Huston for Life Magazine, James Agee quotes the director as saying, “On paper, all you can do is say something happened, and if you say it well enough the reader believes you. In pictures, if you do it right, the thing happens, right there on the screen.” The thing is, for too much of The Other Side of the Wind’s running time, the thing does not happen on screen. Jake’s past sexual predilections, his difficult on-set behavior, his troubled family history, his relationship with John Dale — all these and more are described in dialogue rather than directly depicted. When dramatic revelations occur, they usually do so off-camera, or refer to events that took place before the movie began. And what should be the climactic action of the story — Jake’s failed attempt to seduce John Dale, which leads directly to his accident-which-is-really-a-suicide — feels badly muddled, related to us in a wide shot that reveals nothing, with Huston reciting in voiceover what sounds like dialogue written during an all-nighter in the editing room.

It seems absurd to criticize one of the towering dramatic artists of the 20th century for failing to heed the Screenwriting 101 commandment of “Show, don’t tell,” but it also seems unavoidable, as The Other Side of the Wind lurches from one long scene of exposition to the next, relieved only by even longer scenes from Hannaford’s failed experimental film, which are dazzling at first but in time come to seem tedious and self-indulgent. The style of the movie remains wondrous throughout, but story-wise, you start to feel the air going out of the balloon. Bob Murawski (The Hurt Locker) shares editing credit with Welles, and what he and his team have pulled off in completing The Other Side of the Wind is remarkable. Still, it’s hard to imagine that Welles wouldn’t have cut the movie down significantly from its current two hours (starting with the film-within-the-film), or come up with ways to make the drama more viscerally felt.

Despite these reservations, I’m eager to revisit The Other Side of the Wind, and it’s such a rich, dense, and subtle film that I expect it’ll reward repeat viewings. Welles’ final gift to us is breathtaking at its best, daring even at its worst, and we’re lucky to have it at last.

— Nelson Kim