(Susanna Nicchiarelli’s biopic on singer Nico, Nico, 1988 is in theaters now in New York and L.A. It begins a nationwide rollout in late August…)

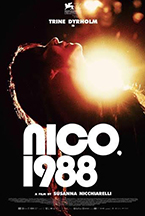

The German-born singer Christa Päffgen, known professionally as Nico, died in 1988 of a cerebral hemorrhage while riding a bike on the island of Ibiza. Like many details of her life, it probably helps to know a few of them to appreciate, in full, the portrait of the artist in her final years that director Susanna Nicchiarelli (Cosmonaut) gives us in Nico, 1988. The film is more elliptical than comprehensive, though engrossing even to the mere initiate, such is the power of the central performance from actress Trine Dyrholm (Troubled Water).

I count myself among such non-aficionados, as I came into this story fairly cold. Yes, I knew (a little) about the Velvet Underground, who kicked off their musical career with vocals by Nico, but not much else. While I was initially thrown off balance looking for narrative support, trying to figure out who the subject was and why she was important, the forward thrust of the dramatic arc, coupled with evocative images, kept me hooked through to the end. Plus, the trajectory of an aging artist struggling against demons internal and external is a familiar one – though here depicted in a refreshingly unique way – and we can all fill in the missing facts of the case as we watch the spectacle at hand.

We start at the end of World War II, as young Christa watches, from afar, Berlin burn. We next jump ahead to Ibiza, where we see Nico mount the fateful bike. Then, through a quick montage of archival 16mm images (or shots made to look like such), we travel backwards to the 1960s and 1970s, during which time Nico (as I discovered through post-screening research) was a model, pre-Velvet Underground, for Andy Warhol, before landing forwards again, in 1986, in Manchester, England, where Nico and her manager Richard (a fine John Gordon Sinclair) are about to launch a new European tour. That transitional jumble of material – repeated, to varying degrees, throughout the film’s flashbacks and dreamscapes – helps explain Nicchiarelli’s decision to film in 4:3 aspect ratio (as opposed to today’s more common widescreen), as does (per the movie’s press notes) her desire to create a 1980s music-video look. Whatever the reason, the overall effect is of a consistent, slightly faded visual aesthetic that suits the subject perfectly.

Between 1986 and 1988, we watch Nico fall (thanks to heroin addiction) and rise again (through recovery), playing concerts to diehard fans and skeptics, alike, many in the soon-to-be-liberated Communist Bloc of Eastern Europe (the cultural dissonance of which makes for both comedy and drama). She’s a force, is Nico (or Christa, as she now prefers to be called), even when a downward one, and Dyrholm is mesmerizing, always, singing the music, herself, including an eerie cover of Alphaville’s “Big in Japan,” played under the end credits. Even when the character is repellant and self-destructive, as she so often is, we understand the creative drive behind her mania, admiring her obsession with the portable audio recorder she always carries in case the perfect soundscape presents itself.

Amazingly, given her drug abuse and narcissism, Nico was also a mother, and her son (also self-destructive, with suicidal tendencies, to boot) – purportedly with an unnamed (in this film) French actor (Alain Delon, who has always denied paternity) – is very much a part of her story here, his own emotional frailty a reminder of the wages of celebrity. Overall, then, this is an impressive work, however one feels about the troubled lead (she was also, apparently, a racist and anti-Semite, something very much downplayed by Nicchiarelli, though the film is hardly a hagiography). See it for Dyrholm and the marvelous rendering of period, and then go look up the missing biographical details when it’s done. Rough stuff, but worth watching.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)