MLK/FBI

(The 2020 New York Film Festival (their 58th!) runs September 17-October 11. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

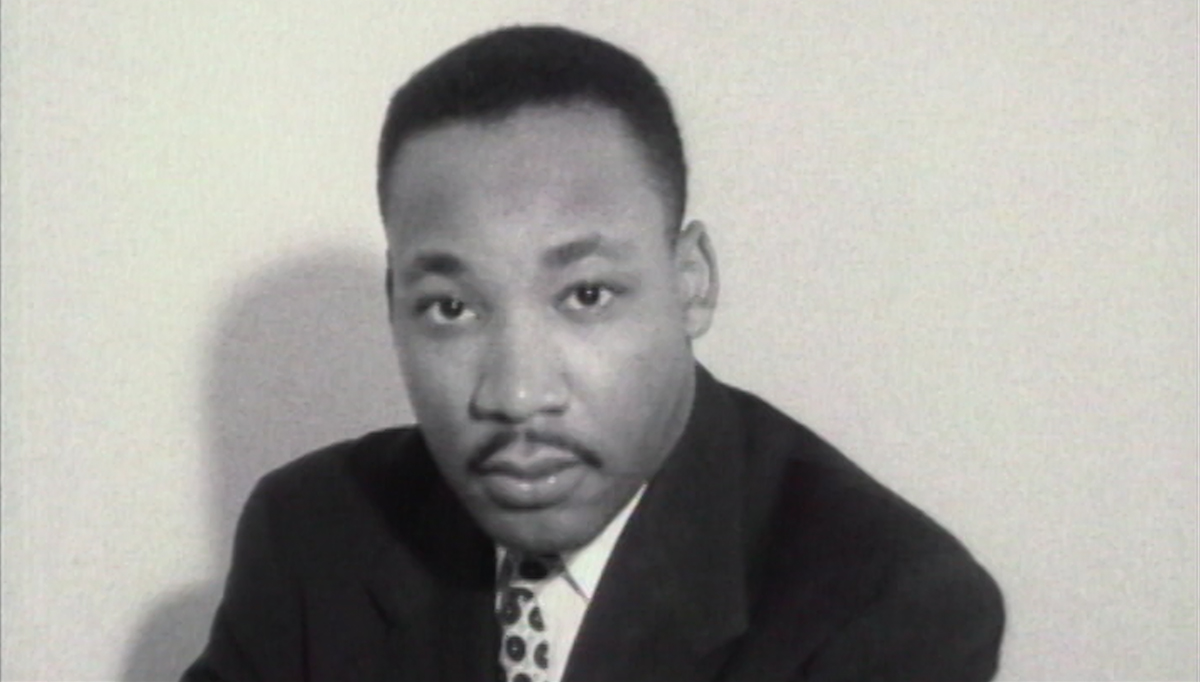

Documentary director Sam Pollard is no stranger to archival footage, with works like Two Trains Runnin’ and Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me (to name but a few) under his cinematic belt, not to mention the many movies he has edited for others, including 4 Little Girls and Chisholm ’72. One might claim he is something of an expert in the genre of historical nonfiction filmmaking, in fact, and with his latest project, MLK/FBI, he puts that skill to marvelous use, delivering an insightful portrait of the life of one of the 20th century’s most important figures at a time when he was hounded and harassed by the top law-enforcement agency of the United States. We may think of Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) today as a beloved Civil Rights icon, but he was not always so cherished while alive, thanks in no small part to the machinations of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In 104 gripping minutes, Pollard examines the how and the why of the anti-MLK actions undertaken by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, a story that proves extraordinarily relevant to our current moment, given the pushback against nonviolent protests by the current occupant of the White House, aided and abetted by Attorney General Bill Barr. Ignore the lessons of the past at your own present peril.

We begin with that seminal moment of King’s career, the 1963 March on Washington, which featured the great “I Have a Dream” speech. And then, suddenly, we break the atmosphere of jubilation and achievement to plunge headfirst into the FBI files that Hoover started accumulating once he began to view King as a threat to society, or “the most dangerous negro in America.” Jumping back and forth between these covert reports and the progress of the Civil Rights movement, Pollard builds, through sharp juxtaposition, the case against the attempts to suppress free speech and dissent. The totality of it all is narrated by a variety of what we would normally call “talking heads,” or experts on the period and on King, except that here we see no one and nothing but what is in the historical material, simple onscreen text informing us who is talking when (finally, at the end, as the credits role, we see their faces). This keeps the focus squarely on MLK and the FBI, where it should be, even if at times it would be nice to know a little bit about the speakers’ qualifications (again, delivered in closing). Some need little introduction, such as former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, but others do.

Pollard also takes us back to King’s early days as an activist (born in 1929, he was surprisingly young during the Montgomery bus boycotts, yet no less effective because of it), always allowing his subject to speak for himself as much as possible. The net result is to emphasize the man’s genius at articulating the essential essence of every matter in concise, clear ways; we really did lose a masterful tactician (who was much more than that, too) when he was assassinated in 1968. In contrast, Hoover comes across as petulant, motivated by fear of change and his own innate racism, and supremely aggressive when it came to matters of, as he chose to see it, sedition. Though President Lyndon B. Johnson was initially an ally of King’s, he later allowed Hoover relatively free reign against the man, especially once MLK spoke out against the Vietnam War. And though there is no indication that the FBI had anything to do with MLK’s death, it is clear that they also did nothing to prevent it.

King was certainly not without flaws – who is? – and the film allows room to discuss those mistakes which allowed Hoover a way to attack. These mostly center around his well-documented marital infidelities; while certainly each person can judge how much such things matter to them, they had nothing to do with whether or not MLK was a communist, the thrust of Hoover’s initial investigations. But relevant or not, the secret audio tapes took their toll on King, as did the negative coverage in the media over his anti-war stance.

Funny that seems, given the reverence MLK is held in now; remember this when you hear today’s leaders express disdain over those taking to the streets in our era. And this is where Pollard’s film gains its true resonance, for this is certainly not the first study of King to make it to the screen. It is in these clear parallels between abuse of power back then and abuse of power in 2020 that MLK/FBI earns its place as a monumental documentary achievement, reporting the facts and condemning by inference. May it open everyone’s ears and eyes, as did King to those who would listen and see.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)