From 18, a 30 year-old can look like a finished person. What often goes unseen are the loose threads: the failed relationships, missed opportunities, nagging regrets. It’s these shortfalls, the mistakes and missteps, that helped build this so-called “complete” person. In Mistress America, the latest collaboration from couple Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig, they’ve together crafted a character who displays the assured poise of a sophisticated young success story but only as these positive traits emerge from the ashes of past failures and held grudges; Gerwig’s character Brooke is a before/after picture, constantly battling to separate the latter from the former, to no avail.

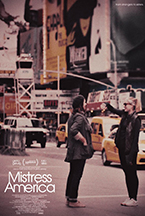

The prism through which we get to see Brooke is Tracy, wonderfully played by Lola Kirke, all lisp, bulky sweaters and misplaced emotions. A college freshman and newcomer to New York, Tracy is adrift and unsure of which version of herself she’s supposed to be. She’s ultimately content to stand at once removed with a writerly affectation she hopes looks sophisticated (much is made of the fact that she writes her fiction on onionskin paper). Tracy’s mom is to marry Brooke’s dad and so the meet cute of Brooke barreling down a flight of red stairs in the middle of Times Square toward Tracy; Gerwig has such presence as a physical comedian that something as simple as descending stairs takes on a not only a comedic slant but also reveals her character, lumbering down the stairs with an elegance tacked on, too late, at the end of each step.

What follows is a platonic romance albeit May/December, Brooke all too happy to impart half-wisdoms, Tracy constantly monitoring the situation, mining for material. Though buoyed by Brooke’s unfailing, addictive positive energy, Tracy as youthful skeptic can’t help but see through Brooke’s veneer; Brooke is all ideas and no follow through. Her current project is a restaurant come hairdresser come community center called Mom’s, a place we come to learn will embody all that she feels is missing from the world around her.

But Brooke can’t do it alone. She enlists the help of boyfriends (past and present), investors, mystics, future stepsisters and ex-best friends to help her reach her goals. And yet, as the restaurant idea begins to recede and Brooke begins to shrink ever so slightly with shoulders slumped, the film seems to ask what Brooke was really after in the first place. A sense of accomplishment, having anything to show for her 20s seems the real imperative and when yet another man wants to simply compartmentalize her into his sexualized being and nothing else — his girl in the city — not even Brooke with her unfailing optimism is able to see a silver lining. She’s been running on fumes for so long she’s starting to get sick from the smell.

This is the second major collaboration between Baumbach and Gerwig, with Frances Ha as an altogether aesthetically different project though with similar pervading themes. Including her role in Baumbach’s 2010 film Greenberg, Gerwig has crafted a triptych of twenty-something women that show three utterly different ways of being young and lost. With each film, the characters have grown in scope and depth; Greenberg’s Florence seems content to wallow in a meandering haze but admittedly is there more so as foil for the titular character (yet proves absolutely as captivating if not more so; Gerwig can change the emotional course of a scene with how she falls on a bed, with how a strand of hair falls across her face). Frances in Frances Ha so wonderfully dances along the line of hopeless inertia and ebullient youthfulness, dancing down the street in one moment, taking a weekend trip to Paris to spite herself the next. And now with Mistress America, her Brooke is a bonafide jack-of-all-trades yet with its inherent flaw of being master of none. When watching these films, I get the overwhelming sensation that I’ve met these three women — they’re iterations of almost everyone I know.

Gerwig and Baumbach don’t try to make Brooke perfect, try as she might to project that image. Early in the film in a slight but crucial scene, Brooke is regaling Tracy in a bar with some tall tale when a former high school classmate approaches. Until now, Brooke comes across as nothing if not magnanimous, an every-woman, friend of the people. This classmate informs her, and Tracy, that she bullied her in high school, constantly. Brooke denies it up and down, yet as the conversation escalates, it becomes clear that not only was this true, but with her back against the wall, Brooke pushes back and bullies the woman again, now without the excuse of a teenage carelessness. She balks when the woman says she’s 30; clearly, Brooke manufactures and carefully curates the narrative of her life and refuses, without exception, to step out of it.

Tracy is infatuated with Brooke, completely enamored by her charm and confidence, not least because she can see through it, and so seems happily complicit on living the lie with her. She writes a short story about the night they first meet, her story sharing the title with the movie they’re in and providing its voiceover narration. To Brooke, her life is exactly that which can’t be shrunk to mere words so she’s predictably incensed to see herself cut down to a couple thousand words when the story comes to light. Yet, while it’s said imitation is the highest form of flattery, it seems that writing about someone is a close second. Perhaps Brooke can’t stand to see herself in print because she can’t stand to see herself, period. On the other hand, it’s clear that despite the fact that Tracy can see each and every crack in Brooke’s armor, it only makes her love and admire Brooke all the more. In a matter of days, Tracy and Brooke go from first love to honeymoon to betrayal to divorce; there’s a simple beauty in seeing the two women warm and cool to each other, sisters one moment, strangers the next.

Baumbach has a knack for showing the intricacies of the artistic process, with its inevitable bruised egos and flushed/blushed faces, dating back to The Squid and The Whale with a lifted Pink Floyd song and a separating couple, unwilling to take each other’s notes. It’s interesting that an approach that no doubt emerges in so many a creative work — writing about those we know intimately — rarely becomes the fodder of the work itself. Late in the film, Tracy tries to make amends with Brooke though when Brooke assumes that Tracy feels remorse for her piece, she matter-of-factly responds that she does not. Brooke stands there stunned for a moment, but then gets it all at once, her fictionalized self does not lessen or negate the living one, if anything it makes her all the more real. Like Tracy’s story, Baumbach and Gerwig’s collaborations feel like they ground their fiction in fact, carried out in a way that’s rare, genuine, and entirely their own.

– Jesse Klein (@jessenoahklein )