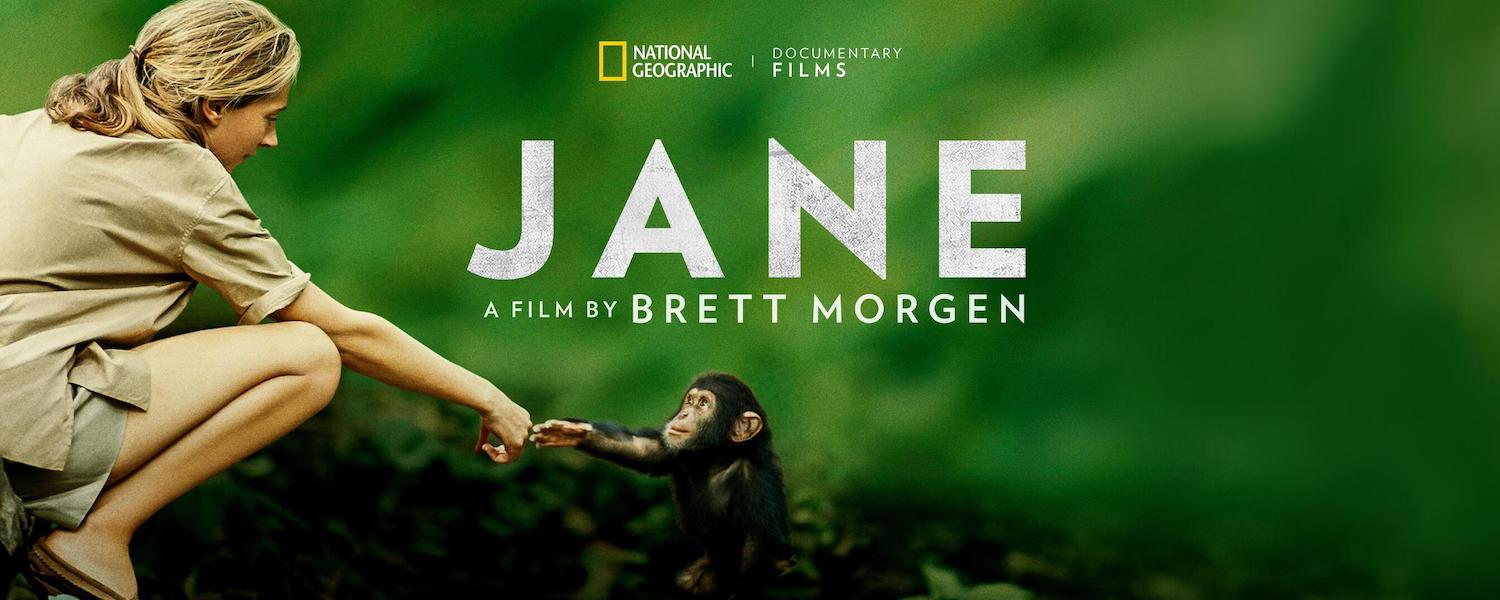

(Brett Morgen’s documentary on Jane Goodall titled simply Jane has been garnering a lot of love of late. The film is in theaters nationwide via National Geographic.)

One of the most remarkable aspects of Jane – a rich and loving portrait of its main subject, famed wildlife biologist Jane Goodall – is that its gorgeous, lush cinematography was mostly shot by a man who died in 2002, Hugo van Lawick. Hired by the National Geographic Society in 1962 to shadow and photograph Ms. Goodall in Gombe Stream National Park, in Tanzania, Baron van Lawick (for he was a Dutch Baron) spent much of the rest of the decade producing images of stunning beauty and color, made all the more remarkable by being the first of their kind. Before Goodall’s studies, no humans had ever recorded such detailed interactions with chimpanzees. Thanks to van Lawick’s expert – and brilliantly artistic – camerawork, we can witness the miracle of discovery, as it happens.

None of this takes away from the additional fine shots produced by veteran cinematographer Ellen Kuras (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), but if there is a reason to see the movie beyond one’s interest in the material, than van Lawick’s photography is it. And then there is Goodall, herself. Untrained when she started, she threw herself into the process of investigating the unknown with tenacity and patience, two of the qualities for which she was selected for the project by anthropologist Louis Leakey, who wanted someone without preconceived notions, but with the capacity to learn. She had adored animals since she was a child, and now seized the opportunity to study our closest ancestors in their natural habitat.

The film, directed by Brett Morgen (Cobain: Montage of Heck), follows Goodall through her arrival in Africa, her early work, her breakthrough with the chimpanzees (when they accepted her and allowed her to touch and be touched), to her love affair, and subsequent marriage to, van Lawick. Yes, love; that no doubt explains the passion evident in his work. Though they would eventually divorce, as their lives inevitably drifted apart with different career opportunities, their relationship – and that with their son Hugo (known as “Grub”) – forms the core of the film, second only to Goodall’s relationship to the great apes.

If the film has a weakness, it’s in its frantic rush to round out the details of Goodall’s life from the end of the 1970s to the present. Though we spend much time with the Goodall of our own era, whose talking-head interview (shot by Kuras) anchors the story, we skip quickly from the end of her marriage to van Lawick to now. What about the intervening 45 years? True, those magical first encounters are riveting, but I, for one, was curious to know more about what Goodall has done since then. Still, whatever reservations I may have about the movie’s narrative trajectory in its final third, I remain deeply moved by the exquisite splendor of the footage, so much of which looks as if it was shot yesterday, since film negatives, when properly preserved, can remain in excellent condition for years. Whether in the past or the present, Jane Goodall has never looked better.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)