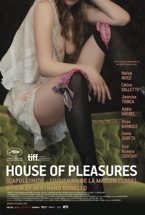

(House of Pleasures, formerly House of Tolerance, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and was picked up for distribution by IFC Films. It is now available on DVD through MPI Home Video. It opened for a limited theatrical release at the IFC Center on November 25, 2011, and is also now available nationwide through VOD. Further, it can be downloaded/streamed for rental at Sundance Now. Visit the film’s official page at IFC Films to learn more.)

There’s a character in Bertrand Bonello’s House of Pleasures most often referred to as the Girl Who Laughs. I say “most often” because, in the first segment, the nickname has yet to come about and the woman is either called the Jewess (itself a problematic a moniker) or Madeleine, her actual name. Each of the prostitutes in L’Apollonide, the eponymous Parisian brothel, has a nickname of her own which acts as shorthand for her most distinct, sellable quality: the Algerian, La Petite, Caca (“I have a specialty,” is all we need to know). Not coincidentally, the horrific moment the Girl Who Laughs is “born” is also the last we see of the year 1899. After focusing on a bloody, shrieking face for several seconds, the screen cuts to black and an intertitle announces that we have moved beyond the twilight of the 19th century and into the dawn of the 20th. An important point of departure, and one whose implications need be sussed out: things may change, but the most resilient aspects bleed through—at least for a while. Time isn’t an entirely linear march from one mode of being to another here; events are often shown out of sequence or simultaneously, granting the proceedings a cyclical feeling that makes their eventual nadir all the more affecting. Bonello offers much on the subject of time, but he’s just as focused on the extreme form of sisterhood his chosen time and place engenders. There’s nothing in the way of backroom politics or betrayal, but rather an unspoken understanding that theirs is a shared burden. It’s hardly uplifting, but neither is it wholly lugubrious.

What is perhaps strangest, most unexpected, and, thanks to a brief but unnecessary coda, essentially inarguable is that all this is in effect a scented love letter to the brothel. Though far from ideal, the women’s shared lot is just that: something of their own, something that unites them. That this comes at the expense of their connection to the outside world and potentially their health is a price all involved seem willing to pay. The only male characters are clients ranging from the oddly benign to the startlingly malicious. They exist not just as foils to their more levelheaded female counterparts but also as a sign of what awaits these women should they ever graduate from L’Apollonide and work on their own: the same danger that makes its way inside, sans the camaraderie. C’est la vie.

Both the women of L’Apollonide and the film itself are aware that this is an era nearing its end—anachronistic music is passed off as diegetic more than once—and as it winds down one is left anticipating an incident just as shocking as that which granted the Girl Who Laughs her unique appellation. Time will slowly make withered roses of them all, and they know it: it’s with unease and disappointment that characters speak of the just-opened metro system and other newfangled inventions. House of Pleasures is lush and languid to the point of creating something like an opium-induced dream state from which neither it nor the viewer ever fully awakens, but it’s also quite remarkable for the way it manages to alarm without resorting to hyperbole. It lets us drift into a deep sleep, but uses seminal fluid and references to Marquis de Sade as nightmare fuel—literally, in the case of the former. (The other literary allusions, to the Bible and The War of the Worlds, combine to form something like a holy-unholy triumvirate.) There are several unexplained incidents and recurring dreams suffused with dread, and often what most matters isn’t the happenings themselves so much as the mood they evoke. Bonello’s film is a tapestry of desire and melancholy as velvety as it is withdrawn: we’re allowed more intimacy than the customers, but the women nevertheless exist in a state of remove which only adds to their mystique.

Both the women of L’Apollonide and the film itself are aware that this is an era nearing its end—anachronistic music is passed off as diegetic more than once—and as it winds down one is left anticipating an incident just as shocking as that which granted the Girl Who Laughs her unique appellation. Time will slowly make withered roses of them all, and they know it: it’s with unease and disappointment that characters speak of the just-opened metro system and other newfangled inventions. House of Pleasures is lush and languid to the point of creating something like an opium-induced dream state from which neither it nor the viewer ever fully awakens, but it’s also quite remarkable for the way it manages to alarm without resorting to hyperbole. It lets us drift into a deep sleep, but uses seminal fluid and references to Marquis de Sade as nightmare fuel—literally, in the case of the former. (The other literary allusions, to the Bible and The War of the Worlds, combine to form something like a holy-unholy triumvirate.) There are several unexplained incidents and recurring dreams suffused with dread, and often what most matters isn’t the happenings themselves so much as the mood they evoke. Bonello’s film is a tapestry of desire and melancholy as velvety as it is withdrawn: we’re allowed more intimacy than the customers, but the women nevertheless exist in a state of remove which only adds to their mystique.

Like the brothel, the film itself is a sensual experience. L’Apollonide hosts all but two scenes of relative brevity, keeping the viewer just as locked away from the outside world as the women for whom it is both workplace and home. “To be free? In a house of tolerance?” asks the incredulous madam to an aspiring prostitute who conceives of the position as a liberating experience, “freedom’s outside, not here.” Even so, the transactional nature of these women’s lives isn’t overemphasized, and, with the exception of the Girl Who Laughs, neither is their degradation. They’re treated instead as facts of life to grin and bear. To lament their fate would, after all, smear their makeup and potentially add to their debts. Madeleine and the other working girls are not unlike indentured servants to their madam; their frequent medical exams, clothing, and perfume are recurring expenses which must be perpetually paid off. They’ve neither freedom nor independence, only the bonds forged by common dolor.

Bonello splits the screen into four squares of equal size on more than one occasion, showing us several scenes at once. L’Apollonide becomes a fragmented panorama, one sometimes blocked in such a way that the characters’ distance from one another is at odds with their body language and the content of their conversations. The only true intimacy here is between the women themselves; everything else is just work. As signaled by the unchaining of a pet panther and onset of syphilis in one of the workers, even this comes to a close. “We deserve our punishment,” one of the women says late in the film. “We deserve the clap.” It’s a startling pronouncement that foregrounds how rapidly things have deteriorated in so little time. At previous nightly gatherings in the parlor, worker and john alike would rub the rim of their champagne flutes in unison so as to produce that pretty, unsettling sound which in a way speaks volumes of House of Pleasures‘s decadent unease. When, at a half-celebratory, half-mournful party marking the death of a sister, the trick no longer works, the madam explains: “It’s not crystal now, just glass.” In their world, this is tantamount to tragedy. Fin.

— Michael Nordine

Pingback: VOD PICKS – Hammer to Nail