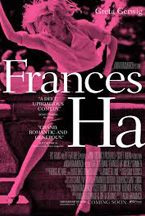

(Frances Ha is now available on Blu-ray/DVD, Amazon Instant, iTunes through Criterion and IFC Films. It world premiered at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival and opened theatrically on Friday, May 17, 2013. Visit the film’s official website to learn more. This review was first published on September 9, 2012, in conjunction with its Canadian premiere at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival.)

Concision has always been at the heart of Noah Baumbach’s films; able to step in and out of scenes at the perfect moment, when just enough information (and often, humor) has been conveyed, never revealing too much or stooping to pure exposition, Baumbach’s films are driven by his actors and their ability to deliver character on time and precisely. Baumbach refuses to linger on his performers, but he gives them ample opportunity to perform and play within the tight restrictions of a scene or shot, and his entire enterprise hinges on their ability to do so; no modern director places so much faith in his actors. Think of Jeff Daniels’ arrogant shagginess in The Squid And The Whale, Nicole Kidman’s mischievous, sinister eyes, always walking the line between certainty and collapse, in Margot At The Wedding, Ben Stiller’s neurotic projections in Greenberg; each of these characters is given great dialogue, sublime jokes, plenty of expressive close-ups, but all in the context of tightly constructed moments that crackle with life.

Of course, the complaint has often been how “unlikeable” many of these characters are, how members of the audience (and surprisingly, the press) have a hard time finding their way to care about them when they can be so downright difficult. Much has been made of unlikeable protagonists in film and whether or not complex characters motivated by self-interest and insecurity (those eternally twinned impulses) are worthy of our sympathies, whether or not they are, well, enjoyable, an issue I’ve always felt to be well beyond the point. Baumbach’s films cut deeply because they are tragic; if there is a hallmark of his work, it is people struggling to be good but always failing, much to their own deep regret, to be the people they imagine themselves to be, the people they cannot, ultimately, become.

This rich (and for me, deeply moving) complexity, this tightrope walk between the struggle for the imagined self and Baumbach’s narrative structure, his tight, revelatory writing, is what makes his work so important. It is also what makes his new film Frances Ha, which he co-wrote with his star Greta Gerwig, at once stylistically consistent and thrillingly new. Working within Baumbach’s structural framework, Gerwig brings her own vision to the film, providing a new point of view, an alert, compassionate voice (both as a writer and an actor) that perfectly compliments Baumbach’s own. Here is the same spitfire rhythm, the same staccato edits that propel Baumbach’s films, but suddenly, in the service of a heroine who, despite struggling with her identity as a twenty-something in New York City, is vibrantly relatable, a good egg who, despite her hilariously valiant efforts, just can’t seem to bend life to her own will.

This rich (and for me, deeply moving) complexity, this tightrope walk between the struggle for the imagined self and Baumbach’s narrative structure, his tight, revelatory writing, is what makes his work so important. It is also what makes his new film Frances Ha, which he co-wrote with his star Greta Gerwig, at once stylistically consistent and thrillingly new. Working within Baumbach’s structural framework, Gerwig brings her own vision to the film, providing a new point of view, an alert, compassionate voice (both as a writer and an actor) that perfectly compliments Baumbach’s own. Here is the same spitfire rhythm, the same staccato edits that propel Baumbach’s films, but suddenly, in the service of a heroine who, despite struggling with her identity as a twenty-something in New York City, is vibrantly relatable, a good egg who, despite her hilariously valiant efforts, just can’t seem to bend life to her own will.

Having recently broken up with her boyfriend, Frances, played with almost impossible charm by Gerwig, is a dancer struggling as an apprentice in an established company, living with her best friend Sophie (a lovely performance from Mickey Sumner) in a small but nice enough apartment in Brooklyn. Importantly, like so many of Baumbach’s best characters, Frances’ professional and romantic struggles don’t inhibit her self-belief; taking each bump in the road in stride, Frances moves forward with certainty, convinced, despite every sign blinking to the contrary, that everything will work out. Instead of being hostile toward life’s impediments, Frances seems almost oblivious to them; everything that happens in Frances’ life seems to come as an unforeseen surprise, a new opportunity to settle in and try something different until another surprise comes along and changes everything all over again.

That openness to life is played for laughs and pathos, and like so much of Baumbach’s work, Frances Ha cuts both ways. The further you travel through the film with Frances, the more you embrace her approach to life, her sense that, despite the overwhelming force of inertia, she is the heroine of some great, yet-to-be-written story. The contradiction is, of course, that life is happening, everywhere and always; a beautifully staged scene of Gerwig running and pirouetting through the streets of Manhattan sings with the joy of being alive, only to cut directly to Frances entering an empty apartment, her arrival an empty denouement to the imagined adventure she has just created. Gerwig inhabits the role completely, creating a fully formed character who is full of joy and doubt, looking for that unknown something.

That openness to life is played for laughs and pathos, and like so much of Baumbach’s work, Frances Ha cuts both ways. The further you travel through the film with Frances, the more you embrace her approach to life, her sense that, despite the overwhelming force of inertia, she is the heroine of some great, yet-to-be-written story. The contradiction is, of course, that life is happening, everywhere and always; a beautifully staged scene of Gerwig running and pirouetting through the streets of Manhattan sings with the joy of being alive, only to cut directly to Frances entering an empty apartment, her arrival an empty denouement to the imagined adventure she has just created. Gerwig inhabits the role completely, creating a fully formed character who is full of joy and doubt, looking for that unknown something.

The film is also a New York movie, with gorgeous black and white cinematography that will draw comparisons to that great New York City love letter, Woody Allen’s Manhattan, but unlike that film’s use of grand exteriors to contrast the small concerns of human relationships, Frances Ha is a film of interiors and faces, of the lives of young creatives navigating low rents and temporary relationships as they search for their place in the world. Ultimately, this is where Frances Ha marks a shift for Baumbach who, instead of tracking the impossibility of redemption, delivers generosity and possibility for his heroine. I couldn’t say where Gerwig’s work ends and Baumbach’s begins, but it is clear that by collaborating, they have expanded one another’s palettes and ideas; both do some of their finest work in this movie. Frances Ha is Baumbach’s most hopeful film; unburdened by regret, it sings to the rhythms of life and experience, smiling at loss and triumph in equal measure.

— Tom Hall

Colin Stanfield

Great review Tom!

Pingback: HOME VIEWING PICKS – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: THE 2013 HAMMER TO NAIL AWARDS – Hammer to Nail