FIRE MUSIC

(Filmmaker and musician Tom Surgal’s documentary Fire Music, on the astonishing sounds (and sights) of the free jazz movement counts musicians Nels Cline and Thurston Moore among its executive producers. The film is in select theaters now. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

We have been led astray by popular music. Our ears have become maladapted; they have been made lazy. Endless hours of popular music have trained us to search for patterns, to resolve harmonies, to become hypnotized by the predictable verse-chorus-verse blueprint. Director Tom Surgal’s documentary Fire Music is a lively history of what is perhaps one of the most experimental music genres, free jazz. Interviews with musicians and jazz journalists give us a buffet sampler of the personalities of free jazz, the time and the places wherein it developed, and its aesthetic significance.

We first require a definition of free jazz; but therein lies the problem — how does one describe the auditory by way of words? The best attempt at a definition is given at the beginning of Fire Music. If one were to move from the structure of the blues, to the looser structure of early jazz, to the even looser structure of bebop, the next logical step is the non-structure of free jazz. Free jazz is music at its most avant-garde. It is improvisational music without a strict adherence to chord progressions. Harmonies do not satisfyingly resolve themselves in free jazz. Perhaps a better way of defining free jazz for the uninitiated is by describing what it is not. Free jazz is not easy listening smooth jazz, or bebop, or swing. Free jazz presents us with the following question: why should art be exclusively something that is enjoyable? In other words, art can be challenging. It is precisely that challenge that makes free jazz exciting.

The stories musicians tell, especially jazz musicians, are usually spellbinding. Ornette Coleman can be rightfully called the father of free jazz. His historical significance in jazz is indisputable; however, those who played with him recount his rocky start. His innovations were maligned. Bandmates recount that Coleman was beat up by other musicians who did not like his experimentation. This was no small squabble with a couple of punches thrown in for effect. In fact, Coleman was beaten so badly that he suffered a collapsed lung. Fire Music compiles stories about free jazz greats such as Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry, and Albert Ayler. The stories offer the early excitement and freedom that being part of an avant-garde artform gave these musicians. They also tell of the struggles these pioneers faced. In the case of many of these free jazzers, poverty was the tradeoff they were willing to accept for making music that was not accepted by the mainstream. In the case of Albert Ayler, the challenges became overwhelming. He committed suicide at the age of 34. And then there’s the oversized personalities of Sun Ra and Prince Lasha. Sun Ra’s Arkestra was part orchestra part cult while Lasha feels like the individual whose side you never want to leave at a party; he oozes charisma and wit.

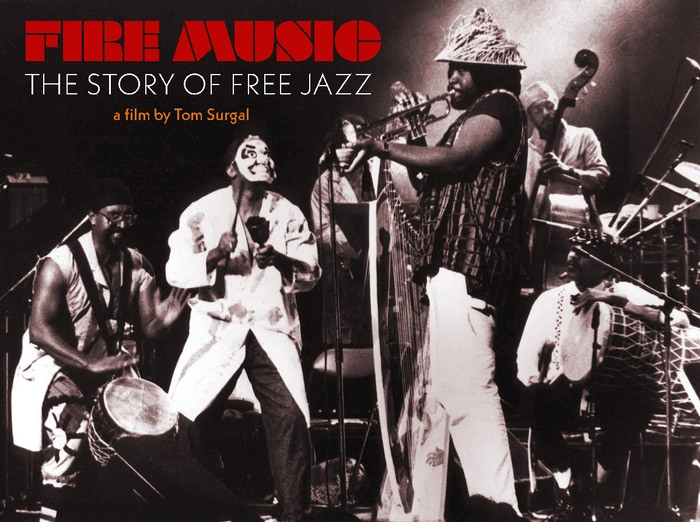

Musician Sun Ra

(photo via Baron Wolman)

Fire Music consists of more than just stories of the road and the early bumpy origins of free jazz. It adeptly shows how some mainstream beboppers like Mingus and Coltrane recognized the importance of free jazz and started moving their music toward a freer direction. Even the great Miles Davis, who was at first critical and outright nasty in his comments about free jazz, eventually recognized free jazz’s innovations. Fire Music captures the electricity, the sense of boundless possibilities, in the New York City of the late 50s, 60s, and 70s. Some of these jazz pioneers lived within the same few blocks. They transformed lofts into performing spaces. Eventually, increasing rents and gentrification forced out these musicians and homogenized neighborhoods. Fire Music recounts what was perhaps the most avant-garde aspect of free jazz. Free jazz musicians attempted to form guilds and unions that would give them leverage in demanding more artistic control and livable wages.

Music has become increasingly commercialized, homogenized, and boring since the experimentation of the 60s and 70s. It is as if the 80s and everything since has been nothing more than a recycling of styles intended to make profit. The experimentation of earlier decades was clipped off. Sonic possibilities were foreclosed. Few feelings are as rewarding as listening to music that feels fresh, that pushes the listener, that expand one’s horizons. When in rock one listens to bands like Swans or Throbbing Gristle, one feels anything is possible. When I first heard Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, I remember sweating and my heart racing. Once you feel that rush, it is hard going back to verse-chorus-verse.

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13)

Submarine Deluxe; Tom Surgal; Fire Music documentary film review