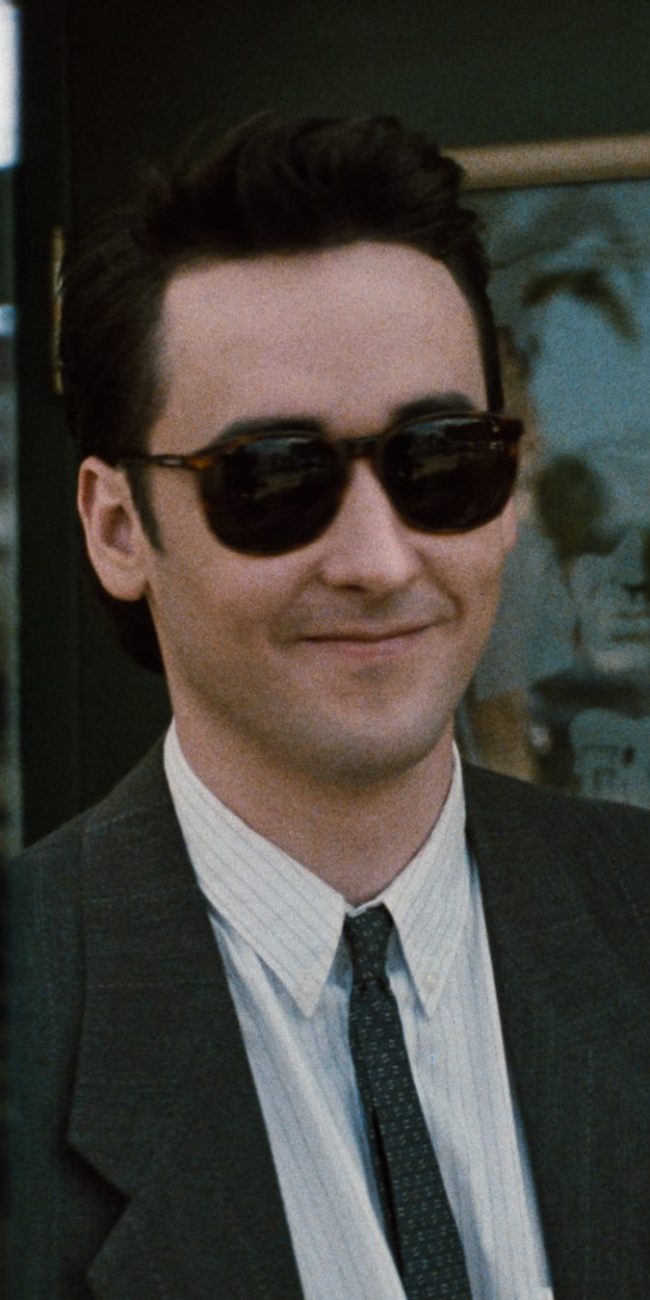

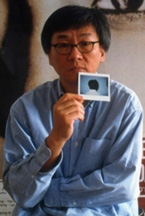

EDWARD YANG: A RETROSPECTIVE

(The Film Society of Lincoln Center’s retrospective A Rational Mind: The Films of Edward Yang runs from November 22 through 27 at the Walter Reade Theater. Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day screens at the Film Society’s Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center from November 25 through December 1.)

Edward Yang was a leading figure in what’s sometimes called the “New Taiwan Cinema” movement that rose to prominence in the 1980s—a group of filmmakers that revitalized the country’s cinema by exploring aspects of its culture and history never before put on screen. The movement emerged as Taiwan was shaking off its long history of authoritarian rule (centuries of foreign domination followed by decades of martial law); strict censorship laws were loosening, and there was a new spirit of openness in the arts. Yang’s special contribution was his obsessive focus on capturing the feeling of contemporary city life, primarily in Taipei, where he saw a society shaped by rigid Confucian values rushing full speed ahead into the hypercapitalist future. But his piercing vision of urban anomie, drift, and desolation has proved to have worldwide relevance.

Two movies screening in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s retrospective, A Rational Mind: The Films of Edward Yang, made a decade apart, showcase Yang’s brilliance at mapping out criss-crossing lines of fate in complex multi-strand narratives. The Terrorizers (1986) keeps us guessing for some time how the lives of its characters—a young Eurasian prostitute, the photographer who’s obsessed with her, a troubled husband and wife, and others—will eventually intersect. The film provides the patient viewer with some answers, but its conclusion raises even larger questions as to the reality of the story we’ve been watching. Postmodernist flourishes aside, The Terrorizers cuts deepest in its depiction of frustrated longings and stifled ambitions; it’s a bummed-out ballad of bad vibes that should speak to the misanthropic side of many a city-dweller.

Two movies screening in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s retrospective, A Rational Mind: The Films of Edward Yang, made a decade apart, showcase Yang’s brilliance at mapping out criss-crossing lines of fate in complex multi-strand narratives. The Terrorizers (1986) keeps us guessing for some time how the lives of its characters—a young Eurasian prostitute, the photographer who’s obsessed with her, a troubled husband and wife, and others—will eventually intersect. The film provides the patient viewer with some answers, but its conclusion raises even larger questions as to the reality of the story we’ve been watching. Postmodernist flourishes aside, The Terrorizers cuts deepest in its depiction of frustrated longings and stifled ambitions; it’s a bummed-out ballad of bad vibes that should speak to the misanthropic side of many a city-dweller.

Mahjong (1996) sketches a (mostly) comic portrait of Taipei as a end-of-the-millennium global boom town, setting an international cast of characters—a naive young Frenchwoman, a pompous British businessman, a cheerfully cynical American madame—in motion alongside an assortment of native Taiwanese strivers, hustlers, and hoodlums. Mahjong is a wild ride of a movie marked by extreme tonal shifts: at times it feels like a brittle social comedy, a slapstick farce, an ultraviolent gangster flick, and a dirty-realist art film were tossed in a blender and the resulting mixture was hurled at the screen by an angry monkey. Some of the mood-and-tempo changes don’t completely come off, and the performances are uneven, but the film’s energy and inventiveness keep it highly watchable throughout.

Mahjong (1996) sketches a (mostly) comic portrait of Taipei as a end-of-the-millennium global boom town, setting an international cast of characters—a naive young Frenchwoman, a pompous British businessman, a cheerfully cynical American madame—in motion alongside an assortment of native Taiwanese strivers, hustlers, and hoodlums. Mahjong is a wild ride of a movie marked by extreme tonal shifts: at times it feels like a brittle social comedy, a slapstick farce, an ultraviolent gangster flick, and a dirty-realist art film were tossed in a blender and the resulting mixture was hurled at the screen by an angry monkey. Some of the mood-and-tempo changes don’t completely come off, and the performances are uneven, but the film’s energy and inventiveness keep it highly watchable throughout.

Among the films playing in the Walter Reade series that I haven’t seen are Taipei Story (1985), a downbeat drama starring Yang’s first wife Tsai Chin and his fellow New Taiwan Cinema luminary Hou Hsaio-hsien as a married couple growing apart, and A Confucian Confusion (1994), a satire on Taipei’s yuppie class. Both are admired by Yang devotees, with Taipei Story in particular often cited as a major work.

Although Yi Yi (2000) was to be Yang’s final feature—colon cancer killed him in 2007, at the age of 59—it was where most viewers first discovered him, marking his breakthrough into the international mainstream after well over a decade as an art-house and festival darling. Yang initially had the idea of making a movie that would show a man’s entire life from birth to death, then realized he could cover the same ground by contrasting the different generations within a single family. A middle-aged high-tech entrepreneur wonders about the different paths he might have taken, following a chance encounter with an ex-lover. His wife, whose elderly mother is slipping toward death, undergoes a spiritual crisis. Their teenage daughter falls in love for the first time. Their pre-pubescent son begins to grow curious about the world around him. All the family members are trapped within their solitary struggles and subjective viewpoints, but the movie allows us to see how their experiences mirror one another’s, a grandly generous act of empathy and a neat reversal of the earlier movies’ emphasis on isolation and disconnection. Yi Yi is nearly three hours long but seems much longer—I mean that as a tribute to how much life it packs into its running time. Leaving the theater in a state of astonishment eleven years ago, I knew I’d seen a masterpiece; repeated viewings haven’t dimmed my enthusiasm in the slightest.

Although Yi Yi (2000) was to be Yang’s final feature—colon cancer killed him in 2007, at the age of 59—it was where most viewers first discovered him, marking his breakthrough into the international mainstream after well over a decade as an art-house and festival darling. Yang initially had the idea of making a movie that would show a man’s entire life from birth to death, then realized he could cover the same ground by contrasting the different generations within a single family. A middle-aged high-tech entrepreneur wonders about the different paths he might have taken, following a chance encounter with an ex-lover. His wife, whose elderly mother is slipping toward death, undergoes a spiritual crisis. Their teenage daughter falls in love for the first time. Their pre-pubescent son begins to grow curious about the world around him. All the family members are trapped within their solitary struggles and subjective viewpoints, but the movie allows us to see how their experiences mirror one another’s, a grandly generous act of empathy and a neat reversal of the earlier movies’ emphasis on isolation and disconnection. Yi Yi is nearly three hours long but seems much longer—I mean that as a tribute to how much life it packs into its running time. Leaving the theater in a state of astonishment eleven years ago, I knew I’d seen a masterpiece; repeated viewings haven’t dimmed my enthusiasm in the slightest.

Yi Yi is the only one of Yang’s films to have enjoyed wide distribution in the U.S., and the only one that’s easy to find on home video—there’s an excellent Criterion edition available on DVD and Blu-ray. But that’s no reason to miss it at Lincoln Center. Here as in all his movies I’ve seen, Yang relies on long takes shot from medium-wide to wide distance, and his detail-packed frames and slow-to-build narrative rhythms are made for the big-screen experience.

Across the street from the Walter Reade, at the Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center, Yang’s four-hour epic A Brighter Summer Day (1991) will screen for a week starting on November 25. Plenty of cinephiles have named A Brighter Summer Day as one of the great modern films, but after only one viewing, I’m not ready to go there yet. (I’ll go there with Yi Yi, any day.) I will say that the movie is an amazingly rich, layered work of historical reconstruction—it’s set during the early ‘60s, when Yang himself was the same age as the mostly teenage characters. A Brighter Summer Day springs from what we can only assume must be very personal, even autobiographical sources, but the events depicted are viewed from a detached, adult perspective. Many of the characters are the children of expats who fled Mainland China following the Communists’ 1949 victory (as Yang himself was); they live in Japanese-style houses, sing along with American pop songs on the radio, and fight with the children of the native-born Taiwanese. The continuities being traced here are clear: even when summoning the ghosts of his past, Yang was always looking forward to our modern world of perpetual displacement and unsettled, ever-shifting identity.

Across the street from the Walter Reade, at the Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center, Yang’s four-hour epic A Brighter Summer Day (1991) will screen for a week starting on November 25. Plenty of cinephiles have named A Brighter Summer Day as one of the great modern films, but after only one viewing, I’m not ready to go there yet. (I’ll go there with Yi Yi, any day.) I will say that the movie is an amazingly rich, layered work of historical reconstruction—it’s set during the early ‘60s, when Yang himself was the same age as the mostly teenage characters. A Brighter Summer Day springs from what we can only assume must be very personal, even autobiographical sources, but the events depicted are viewed from a detached, adult perspective. Many of the characters are the children of expats who fled Mainland China following the Communists’ 1949 victory (as Yang himself was); they live in Japanese-style houses, sing along with American pop songs on the radio, and fight with the children of the native-born Taiwanese. The continuities being traced here are clear: even when summoning the ghosts of his past, Yang was always looking forward to our modern world of perpetual displacement and unsettled, ever-shifting identity.

— Nelson Kim