In 1971, actress Barbara Loden made her directorial debut with Wanda, a work so uncompromising that it could easily pass as the paradigm example of American independent filmmaking. A Hollywood actress by trade (best known for her supporting role in Splendor in the Grass), Loden had no practical background or training in filmmaking when she landed on the idea of directing this intensely personal project. But her drive to realize it drove her to forgo looking for conventional studio financing, ignore sound judgment (most coming from her then husband, Elia Kazan), and simply throw herself face-first into the process. Made over the course of ten weeks, largely self-financed and shot on 16mm reversal film with a crew of only four people, Loden produced something brutally raw, relentlessly downcast and unapologetically small in scope. And so, after an auspicious premiere at the Venice Film Festival (where it won top prize), the film failed to obtain proper distribution and outside of one theatrical engagement in New York, disappeared from circulation almost entirely.

In the decades since, a loyal cult has formed around Wanda, thanks to occasional museum screenings, a domestic release of the movie on DVD and a successful theatrical re-release of it in Europe. But while movies like Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman (which shares Wanda’s interest in confronting the broken promises attendant to living as a women during the ’70s liberation movement), and the works of Cassavetes (which shares its rough-hewn style) are recognized as landmark achievements, one wonders why Wanda is still screened and discussed so rarely. It deserves to be celebrated this weekend on the big screen because personal and risky works like this are still so frustratingly rare.

Ms. Loden was inspired to write the film after reading a newspaper article about a woman who was implicated in a bank robbery and thanked the judge after he sentenced her to twenty years in prison. What type of woman would feel relief and gratitude at being banished to rot in jail? Wanda becomes a meditation on this question. The movie presents us with a new kind of female archetype; a woman compelled to drop out of housewifery and motherhood without giving us a rationale. What makes her choice simultaneously fascinating and upsetting is that she is not leaving her life for any tangible alternative, plan or ideal. While standing before a judge to grant her estranged husband a divorce, Wanda doesn’t look longingly, regretfully, angrily or shamefully at her husband or young children. In fact, she doesn’t look in their direction at all. She simply and blankly explains to the court that they’d be better off without her. While men who abandon family life are a veritable Hollywood/literary trope, presented through the lens of recklessness or guilt but still shaded in all sorts of attractive ways, a woman who does not have some sort of innate instinct to care for her own children seems scary and damaged, almost dangerous.

Ms. Loden was inspired to write the film after reading a newspaper article about a woman who was implicated in a bank robbery and thanked the judge after he sentenced her to twenty years in prison. What type of woman would feel relief and gratitude at being banished to rot in jail? Wanda becomes a meditation on this question. The movie presents us with a new kind of female archetype; a woman compelled to drop out of housewifery and motherhood without giving us a rationale. What makes her choice simultaneously fascinating and upsetting is that she is not leaving her life for any tangible alternative, plan or ideal. While standing before a judge to grant her estranged husband a divorce, Wanda doesn’t look longingly, regretfully, angrily or shamefully at her husband or young children. In fact, she doesn’t look in their direction at all. She simply and blankly explains to the court that they’d be better off without her. While men who abandon family life are a veritable Hollywood/literary trope, presented through the lens of recklessness or guilt but still shaded in all sorts of attractive ways, a woman who does not have some sort of innate instinct to care for her own children seems scary and damaged, almost dangerous.

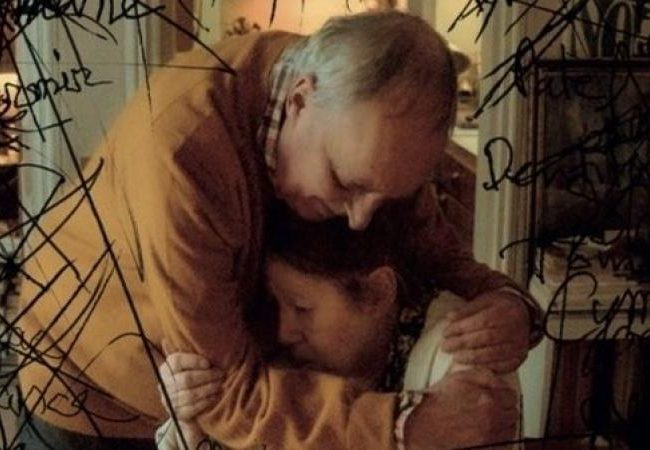

In Wanda, Ms. Loden’s performance is so understated and unsentimental that it is easy to assume Wanda is a woman completely unaffected by her own circumstances. Ms. Loden refuses to visually or verbally externalize the emotional world of her character. She actively denies us any kind of easy reading of her internal state and instead reveals only what Wanda herself is willing to let the world in on: nothing. She is numb. She is scared. She is without choices. The performance acts as a true mirror, without distortions, semaphores or explanations. There is some relief for Wanda when she meets Mr. Dennis, a man who immediately expects her to slip into a passive position as his on-the-road companion. How wonderful to be steered and not be behind the wheel, how liberating to not be making the choices. But when Mr. Dennis requires her to play the role of benign pregnant wife during the film’s nerve-wracking climax, Wanda comes full circle. Isn’t this the role she was just running away from?

But of course, Wanda is not a love story or a bank heist film. It is the relentlessly tragic portrait of a woman who cannot find herself because she has no idea where to look. The woman on display in the haunting freeze-frame that closes the film is not someone who has finally given up; she’s lost nothing, she’s loved nothing, she knows nothing, she wants nothing.

— Mary Bronstein

(Wanda screens this weekend at the Walter Reade as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series “Mavericks and Outsiders: Positif Celebrates American Culture.” Or if you are unable to catch it on the big screen, buy the DVD at Amazon.)