(Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy is available from Amazon.)

The challenge is to see things with a fresh eye. When a film has been called a “classic” for too long, it comes to us cloaked in a fog of received opinion, textbook platitude, knee-jerk veneration, and other impediments to clear perception. In the case of Rome Open City (1945)—the first film in the Criterion Collection’s new DVD box set, Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy—the fog is especially thick. We’re not talking about your average, everyday classic here. This is one of the epochal, paradigm-shifting events in cinema history, the grubby, stitched-together DIY indie that announced a renaissance in the cultural life of its nation and set off the Italian Neorealist movement—a movement whose influence was immediate, worldwide in scope, and enduring: to this day, whenever filmmakers reject studio artifice and escapist story formulas in favor of capturing observable social reality and everyday behavior, they’re said to be working in the Neorealist tradition.

One of the first things a contemporary viewer notices about Rome Open City is that it doesn’t really conform to the standard definition of what a Neorealist film is supposed to be. Rossellini casts polished professional actors alongside plucked-from-the-streets amateurs, alternates highly stylized lighting and studio sets with the newsreel-like immediacy of the on-location sequences, and employs crowd-pleasing melodrama and thriller devices to leaven his tough critiques of the moral, social, and political squalor of wartime Italy. But so what? We can hardly fault a work of art for not fitting neatly into the categories that critics generate after the fact—and this mixture of modes provides much of the film’s vigor.

However, the mixture doesn’t completely gel; this certifiably Great Film isn’t always a very good movie. The problem isn’t melodrama. The problem is thuddingly crude melodrama of the sort that intelligent audiences in the silent era would’ve jeered at. Take the two primary villains of the piece, the gay Nazi commanding officer and his drug-pushing lesbian henchwoman. It’s not even a question of contemporary sensibilities finding such caricatures ludicrously outdated—no, the loathsome queers represent a larger artistic failure: not only are the actors’ performances embarrassing to behold, but by reducing the evil of Nazism to sexual “perversion,” Rossellini nearly tanks the entire film’s attempt to give an honest account of life under Fascism, and sullies its claim to seriousness, as drama, as reportage, as history.

And yet, the bad walks hand in hand with the good: that same drive toward melodrama lends many of the film’s strongest scenes an operatic, larger-than-life emotional intensity: Anna Magnani’s aria-like lament to the priest (”How will we ever forget all this suffering… Doesn’t Christ see us?”), the heroic refusal of the Communist Resistance fighter to break under torture, the wrenching moment when the priest curses his Nazi captors and then, seconds later, begs God’s forgiveness for allowing hatred to get the better of him. Everything Rossellini is aiming for—documentary rawness fused with the total audience involvement of great pop filmmaking—comes together perfectly in the long sequence that ends the first half of the film: the raid on the apartment building, which rivals anything in Hitchcock for white-knuckle suspense, and culminates in Magnani’s murder, one of the most famous scenes in world cinema. As with Potemkin’s Odessa Steps massacre or the shower stabbing in Psycho, overfamiliarity can never dull the power of this series of images; all the ubiquitous picture-book frame enlargements and reams of critical commentary vanish from the mind once the scene begins to unfold.

And yet, the bad walks hand in hand with the good: that same drive toward melodrama lends many of the film’s strongest scenes an operatic, larger-than-life emotional intensity: Anna Magnani’s aria-like lament to the priest (”How will we ever forget all this suffering… Doesn’t Christ see us?”), the heroic refusal of the Communist Resistance fighter to break under torture, the wrenching moment when the priest curses his Nazi captors and then, seconds later, begs God’s forgiveness for allowing hatred to get the better of him. Everything Rossellini is aiming for—documentary rawness fused with the total audience involvement of great pop filmmaking—comes together perfectly in the long sequence that ends the first half of the film: the raid on the apartment building, which rivals anything in Hitchcock for white-knuckle suspense, and culminates in Magnani’s murder, one of the most famous scenes in world cinema. As with Potemkin’s Odessa Steps massacre or the shower stabbing in Psycho, overfamiliarity can never dull the power of this series of images; all the ubiquitous picture-book frame enlargements and reams of critical commentary vanish from the mind once the scene begins to unfold.

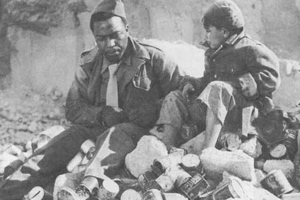

Even before Open City was released to massive international acclaim, Rossellini had begun preparing its follow-up. Paisan (1946) consists of six short stories, each taking place in a different region of Italy, all linked by a common subject—the relationship between the Americans who arrived in 1943 and the Italians who saw them as both occupiers and liberators—and a common theme: the necessity, and the difficulty, of bridging the gap between nations, cultures, and languages. A Sicilian peasant girl and an infantryman from New Jersey spend a few hours waiting for his platoon to return from a recon mission. A Neapolitan street urchin befriends a black M.P., who comes to a belated recognition of their shared suffering. In Rome, a G.I. reunites with a girl he’d fallen for months earlier, but the hardships both have endured since make them strangers to each other now. An American nurse and a partisan sympathizer set out on a hazardous journey through a Florence under fire. Three U.S. Army chaplains receive a strange and unexpected welcome at a monastery in Romagna. A beleaguered band of OSS operatives and partisans fight side by side in the marshlands of the Po River Valley.

Rossellini hits upon a brilliant device to buttress the authenticity of his fiction with facts: he begins each section with newsreel footage as an announcer sets the scene—”On the night of July 10, 1943, the Allied fleet opened fire on the southern coast of Sicily,” and so on—before smoothly easing us into the invented tale. Though Paisan is as much a synthesis of different forms and styles as Open City, the multipart construction of the narrative hides the seams better, paradoxically giving the entire work a greater sense of unity. The conclusions of most of the stories are grim—communication breaks down, hope gives way to despair, the enemy takes the upper hand—but the film is shot through with flashes of moral illumination and mutual understanding, fleeting moments of connection and compassion. Paisan is a deeper, more searching exploration of the territory Open City had scouted; its break with earlier cinematic traditions is cleaner, its embrace of the new more assured and decisive.

Rossellini hits upon a brilliant device to buttress the authenticity of his fiction with facts: he begins each section with newsreel footage as an announcer sets the scene—”On the night of July 10, 1943, the Allied fleet opened fire on the southern coast of Sicily,” and so on—before smoothly easing us into the invented tale. Though Paisan is as much a synthesis of different forms and styles as Open City, the multipart construction of the narrative hides the seams better, paradoxically giving the entire work a greater sense of unity. The conclusions of most of the stories are grim—communication breaks down, hope gives way to despair, the enemy takes the upper hand—but the film is shot through with flashes of moral illumination and mutual understanding, fleeting moments of connection and compassion. Paisan is a deeper, more searching exploration of the territory Open City had scouted; its break with earlier cinematic traditions is cleaner, its embrace of the new more assured and decisive.

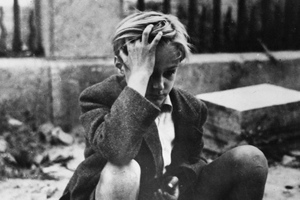

Rossellini closes out his war trilogy with an investigation of what the war had done to Germany, Italy’s former ally turned oppressor, now fallen into defeat and disgrace. The previous films had been ensemble pieces; Germany Year Zero (1948) is a single-character study—and what a study, what a character! Thirteen-year-old Edmund (Edmund Meschke) lives in an overcrowded Berlin tenement his family shares with several others. His father is old, ailing, and wracked by self-pity; his older brother, who fought in the German Army, refuses to register with the new government for fear of being arrested as a war criminal, and thus can’t work or put food on the table; his older sister is dangerously close to turning tricks to help them all survive. Edmund navigates the rubble of his broken city, in search of sustenance of any kind—money, food, guidance, companionship, a reason to live. None are to be found. (Rossellini had lost his young son Romano to illness in 1946, which presumably added to the story’s unremitting bleakness.)

Germany Year Zero burns through its 73 minutes with relentless energy, powered by a fluent moving camera and drum-tight narrative logic. In the nearly wordless ten-minute sequence that concludes the film—which Rossellini would later claim was his sole motivation for making it—Edmund, having committed a horrible crime and then realizing he’s beyond redemption, wanders the streets aimlessly until he reaches the end of the road, in every sense. Emotionally, the sequence is depressing, but as a piece of filmmaking, it’s exhilarating: Rossellini is pointing the way forward to much that is most fruitful in modern cinema, a cinema that seeks to depict interior states of mind and feeling without relying on hand-me-downs from 19th-century literature and theater. His younger compatriots Fellini (who had worked on the scripts for Open City and Paisan), Antonioni, and Pasolini, among others, would contribute to this new way of seeing—but so would Rossellini himself; by the time of his 1950s collaborations with Ingrid Bergman, he had left Neorealism behind to be part of this second vanguard, using modernist formal innovations to express a personal vision of spirituality. (1953’s Voyage to Italy, in particular, is as radical as L’Avventura or any films of the French New Wave, whose leading lights were proud to name Rossellini as a progenitor.) Picasso-like in his metamorphoses, he would then move on to a third major phase in the ’60s and ’70s, with a highly original series of biographical/historical portraits. But it all begins with the wartime trilogy. Criterion has once again done film lovers a great service in making these essential works available to a wider audience.

Germany Year Zero burns through its 73 minutes with relentless energy, powered by a fluent moving camera and drum-tight narrative logic. In the nearly wordless ten-minute sequence that concludes the film—which Rossellini would later claim was his sole motivation for making it—Edmund, having committed a horrible crime and then realizing he’s beyond redemption, wanders the streets aimlessly until he reaches the end of the road, in every sense. Emotionally, the sequence is depressing, but as a piece of filmmaking, it’s exhilarating: Rossellini is pointing the way forward to much that is most fruitful in modern cinema, a cinema that seeks to depict interior states of mind and feeling without relying on hand-me-downs from 19th-century literature and theater. His younger compatriots Fellini (who had worked on the scripts for Open City and Paisan), Antonioni, and Pasolini, among others, would contribute to this new way of seeing—but so would Rossellini himself; by the time of his 1950s collaborations with Ingrid Bergman, he had left Neorealism behind to be part of this second vanguard, using modernist formal innovations to express a personal vision of spirituality. (1953’s Voyage to Italy, in particular, is as radical as L’Avventura or any films of the French New Wave, whose leading lights were proud to name Rossellini as a progenitor.) Picasso-like in his metamorphoses, he would then move on to a third major phase in the ’60s and ’70s, with a highly original series of biographical/historical portraits. But it all begins with the wartime trilogy. Criterion has once again done film lovers a great service in making these essential works available to a wider audience.

— Nelson Kim