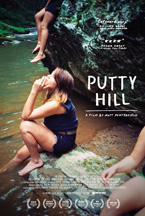

(Putty Hill was picked up for distribution by Cinema Guild and is now available on DVD in a 2-disc Special Edition. It opened theatrically at Cinema Village in New York City on Friday, February 18, 2010. Visit the film’s official website to learn much more, and read Matthew Porterfield’s insightful essay on the how the film came to be. NOTE: This review was first published in conjunction with Putty Hill‘s North American premiere at the 2011 SXSW Film Festival.)

In 2006, Matthew Porterfield gave us Hamilton, a quiet, moody film about two young kids who have just become parents. Taking place over the course of only a couple of days, Hamilton captured the tension between stasis and unrelenting change that was occurring in both their lives, as well as the lives of their respective families and friends. Hamilton was impressive not only for its unusually evocative portrait of suburban Baltimore (Porterfield emphasizes atypical parts of the city as only a native could), but also its subtle yet sophisticated handling of the community. One really gets the sense of interconnectivity that is rarely seen outside of attention-mongering ensemble pieces. Instead of yelling from the rooftops, however, Porterfield remains understated in the way that he weaves the network between characters, often privileging implicit, almost instinctual, interactions that hint at something deeper than any explicit exposition could ever achieve.

With Putty Hill, Porterfield has made good on all the promises of Hamilton, creating a film that is at once more redolent and reticent, but that also takes his narrative experimentation another step forward. Returning once more to Baltimore, Porterfield this time explores a group of characters that have all been affected by the death of a young man, Cory, who never appears in the film expect for a photograph at his wake. Up until the penultimate scene, the characters are all shown individually, an effective narrative strategy that underscores the deep sense of isolation that runs throughout the picture. But as much as Cory is the element that binds the characters together, the story is less about him than it is the people that he knew. Each successive scene adds a little bit of pigment to the canvas, but the portrait of Cory remains incomplete. His enigma, however, serves a double purpose. On the one hand, it reminds everyone of their own transience (which seems to last forever, evoking a similar feeling as in Hamilton), but Cory’s mystery also comes to represent the limits of understanding, for both the characters and the audience. Just as his friends silently struggle to grasp his motivation, so do the vague suggestions of addiction and capitulation make Cory seem more real than any concrete facts. In this way, Porterfield also avoids any preachy messages and shows the utmost respect for the characters of Putty Hill. By not presuming to “know” them, he lets them live a little, and allows that their lives are bigger than the hour and a half run time.

Respect is a description I keep coming back to with Putty Hill. It extends beyond the people in the story and becomes a foundational aesthetic for the whole movie, particularly the cinematography by Jeremy Saulnier (who also shot Hamilton and was the director of Murder Party), the location sound recording by Phil Davis and Nick Rush, the sound design by Ben Goldberg, and the editing by Marc Vives. Long takes and environment-specific audio dominate, which combine to give real weight to the time and place of the scenes—a natural rhythm whose deceptive simplicity belies the rigor and artistry behind it. A mother’s voice cutting through the booming sound of heavy metal emitting from behind a teen’s door; echoes of an ice cream truck and a helicopter mixing as a group of young girls walk through a forest, smoking and talking amongst themselves, their voices little more than an evocative element of a richly mixed soundtrack. In a later scene, these same girls sit on a couch, watching television and chatting. As two of them get up and cross the room, the camera follows. The soundtrack, however, stays with the girls on the couch talking about the upcoming funeral, resulting in a complex audio/visual counterpoint that goes completely against every textbook definition of “editing.” It’s an absolutely liberating moment for both the filmmaker and the audience, and shows the sort of delicate revolutions going on just beneath the surface in Porterfield’s films.

Respect is a description I keep coming back to with Putty Hill. It extends beyond the people in the story and becomes a foundational aesthetic for the whole movie, particularly the cinematography by Jeremy Saulnier (who also shot Hamilton and was the director of Murder Party), the location sound recording by Phil Davis and Nick Rush, the sound design by Ben Goldberg, and the editing by Marc Vives. Long takes and environment-specific audio dominate, which combine to give real weight to the time and place of the scenes—a natural rhythm whose deceptive simplicity belies the rigor and artistry behind it. A mother’s voice cutting through the booming sound of heavy metal emitting from behind a teen’s door; echoes of an ice cream truck and a helicopter mixing as a group of young girls walk through a forest, smoking and talking amongst themselves, their voices little more than an evocative element of a richly mixed soundtrack. In a later scene, these same girls sit on a couch, watching television and chatting. As two of them get up and cross the room, the camera follows. The soundtrack, however, stays with the girls on the couch talking about the upcoming funeral, resulting in a complex audio/visual counterpoint that goes completely against every textbook definition of “editing.” It’s an absolutely liberating moment for both the filmmaker and the audience, and shows the sort of delicate revolutions going on just beneath the surface in Porterfield’s films.

While “naturalism” seems to be synonymous with much of independent filmmaking these days, the style seems perfectly suited to Putty Hill. An almost spiritual quality to its quietude and the humanistic joy of the wake distinguish the film and its singular qualities. In fact, I would encourage Porterfield to take this naturalistic sensibility even further in his next film. The two moments of non-diegetic music (a cello accompanies a montage of skateboard and BMX stunts, as well the closing moments of the film as a car drives through the night) stand out as unnecessary, as the music only reiterates qualities that are innate to the footage itself. These breaks in Putty Hill’s established aesthetic might not add to the scenes, but they do remind of the power of restraint that characterizes the rest of the picture.

Putty Hill’s story unfolds in alternating observational shots and documentary-esque encounters between the characters and an off-screen narrator whose presence is never clarified. Within the realm of the story, is this supposed to be the camera operator, or someone else associated with the crew? It remains ambiguous, and after multiple viewings I am tempted (but not wholly convinced) to interpret these private moments in a much more radical way as a variation on the theatrical monologue. These shared moments occur suddenly and disappear just as quickly, and in between time seems to stop. There is something secretive about these dialogues, as though the character speaking (or, in one rare instance, three girls in a pool) is the only one aware of the narrator. Some of the characters are more guarded than others – during the pool scene, one girl runs off camera under the pretense of being cold—but it is never what they say that is most important. Instead, it is that which they realize but do not share, or even acknowledge.

By fusing narrative and documentary techniques, Porterfield has created a film that feels very open. This is not to imply that Putty Hill’s aesthetic strategies are unintentional—on the contrary, the freedom for characters to come and go, and to be as open or closed as they please, is the result of great forethought on the part of the filmmakers. One never wonders whether scenes are improvised or scripted because—and this is what is most important—the non-professional cast lends both sincerity and authenticity to their characters. Roles big and small both leave their indelible impressions on the audience, whether it is Cory’s cousin Jenny (the up-and-coming teenage singer Sky Ferreira, the only name you might recognize in the cast) wandering through her estranged father’s living room/tattoo parlor while shirtless men listen to slow jams and await their turn to get inked; the police officers in the woods wearing shorts, carrying machine guns, and looking for a homicidal bank robber; or a grizzled, bear-like older man at Cory’s wake who scares two little girls when he starts to emphatically boogie-down. Under Porterfield’s empathetic direction, the characters of Putty Hill seem to live and breathe as few do in current cinema. Through them, the simplest actions become captivating, meaning that the film’s weight comes not from any revelatory truths (Porterfield shies away from anything so grandiose), but from modest gestures—delicate actions that, by saying little, speak mountains.

By fusing narrative and documentary techniques, Porterfield has created a film that feels very open. This is not to imply that Putty Hill’s aesthetic strategies are unintentional—on the contrary, the freedom for characters to come and go, and to be as open or closed as they please, is the result of great forethought on the part of the filmmakers. One never wonders whether scenes are improvised or scripted because—and this is what is most important—the non-professional cast lends both sincerity and authenticity to their characters. Roles big and small both leave their indelible impressions on the audience, whether it is Cory’s cousin Jenny (the up-and-coming teenage singer Sky Ferreira, the only name you might recognize in the cast) wandering through her estranged father’s living room/tattoo parlor while shirtless men listen to slow jams and await their turn to get inked; the police officers in the woods wearing shorts, carrying machine guns, and looking for a homicidal bank robber; or a grizzled, bear-like older man at Cory’s wake who scares two little girls when he starts to emphatically boogie-down. Under Porterfield’s empathetic direction, the characters of Putty Hill seem to live and breathe as few do in current cinema. Through them, the simplest actions become captivating, meaning that the film’s weight comes not from any revelatory truths (Porterfield shies away from anything so grandiose), but from modest gestures—delicate actions that, by saying little, speak mountains.

— Cullen Gallagher

Pamela

Spot on, Cullen, fabulous review!

Pingback: Hammer to Nail » Blog Archive » BAMcinemaFEST 2010 – An Overview (Updated Daily!!!)

adamhump

off screen narrator = porterfield (character of “the filmmaker himself”)

this is a kind of authenticity ploy whereby he is “being part of the milieu” I think

I completely disagree with your take on the non-diegetic music. Lack of non-diegetic music is cliche.

This was my favorite film I saw all year, yall should see it.

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail