(Paid in Full is available on DVD and Blu-ray.)

Early on in Charles Stone III’s 2002 crime drama Paid in Full, there’s a scene where Ace (Wood Harris), a straight-and-narrow young man beginning to succumb to the allure of drug dealing, goes to see De Palma’s Scarface remake in a Harlem theater. The Uptown crowd loses their minds, stomping and hollering as Pacino’s coke-fueled Tony Montana makes his last stand. This is intercut with a fast-paced, brutal scene of Ace’s friend Mitch (Mekhi Phifer) stalking and killing a thug who robbed one of Mitch’s workers. Stone and his screenwriters, Matthew Cirulnick and Thulani Davis, are playing on multiple levels of reference here. Paid in Full is based on the true story of 1980s Harlem cocaine kingpins AZ (Ace in the movie), Rich Porter (Mitch), and Alpo (Rico, played by the rapper Cam’ron). The trio’s real-life exploits would later become important source material for New York’s next generation of hip hop MCs, including the great triumvirate of Nas, Biggie, and Jay-Z. These rappers created their recording personas by fusing the street legends of their adolescence, the gangster movies they loved, and much-speculated-upon degrees of first-hand experience; in the process, they brought a new level of emotional and lyrical complexity to so-called “gangsta rap.” Stone and his collaborators traced the rappers’ stories back to their source (Cirulnick and Davis worked from an earlier script co-written by the real AZ, aka Azie Faison) and closed the circle: Paid in Full is the cinematic equivalent of Ready to Die and Reasonable Doubt, and one of the best crime films in years.

When Ace cheers on Tony’s kill-crazy rampage as Mitch goes all-out for his money, Stone is at once re-enacting ’80s reality in fictional form, casting a critical eye on the glamorization of thug-and-drug life peddled by both hip hop and Hollywood, and asserting his own film’s place in the gangster-movie pantheon. Paid in Full earns that place not through innovation—there isn’t a single story beat, character type, or visual trope in it that we haven’t all seen a hundred times—but through sheer force of talent and complete emotional commitment to the material. This is genre filmmaking of a very high order: what in lesser hands would come across as a retread of clichés instead takes on a nearly classical grandeur. Even the most inventive contemporary crime movies, like the work of Tarantino and the Coens, sometimes seem to be taking place in a world disconnected from recognizable social reality. Stone, in his first feature film (he was previously best known for the Budweiser “Whazzup?” commercials, and went on to make the crowd pleaser Drumline), yanks the genre out of its closed loop of ever-more-baroque film-geek flourishes, and jolts it full of life.

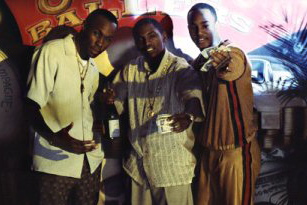

His lead actors couldn’t have been better chosen. You know what’s coming a mile away when Ace, hoofing it around Harlem delivering clothing for his minimum-wage dry-cleaning job, goes slack-jawed as Mitch pulls up in his gleaming new tricked-out Saab. But you’ve never seen a more nuanced rendition of it than the one Wood Harris (who also played Avon Barksdale on The Wire) gives here, self-loathing and covetousness and naked ambition all bubbling up behind his narrow eyes. Cam’ron, a gifted but erratic rapper making his screen debut, is startling in the Joe Pesci role as the buck-wild killer Rico. And Phifer steals the show as the charismatic and flamboyant Mitch, delivering two monologues—one describing his love for hustling, the other, near the end, as he tearfully tells Ace that his younger brother has been kidnapped—that left me gaping at the screen.

His lead actors couldn’t have been better chosen. You know what’s coming a mile away when Ace, hoofing it around Harlem delivering clothing for his minimum-wage dry-cleaning job, goes slack-jawed as Mitch pulls up in his gleaming new tricked-out Saab. But you’ve never seen a more nuanced rendition of it than the one Wood Harris (who also played Avon Barksdale on The Wire) gives here, self-loathing and covetousness and naked ambition all bubbling up behind his narrow eyes. Cam’ron, a gifted but erratic rapper making his screen debut, is startling in the Joe Pesci role as the buck-wild killer Rico. And Phifer steals the show as the charismatic and flamboyant Mitch, delivering two monologues—one describing his love for hustling, the other, near the end, as he tearfully tells Ace that his younger brother has been kidnapped—that left me gaping at the screen.

Some genre-film theorists contend that watching the gangster’s rise to the top appeals to the amoral, asocial will to power in all of us, while his eventual downfall answers to our need to see the social order restored, the transgressor punished, the lid put back on the id. For years, critics of both gangster movies and gangsta rap have argued that the crime-doesn’t-pay moral lessons tacked onto the end of such stories are no match for the ill thrills we get from seeing the bad guy do his thing. (The now-reformed Azie Faison, for one, complained that Paid in Full romanticized the life it purported to condemn.) And the critics have a point: who walks away from either version of Scarface giving a good goddamn about the moral of the story? It’s all about the style, the swagger, the adrenaline rush. (In this respect, GoodFellas was far more forthright, presenting us with a protagonist whose only regret was that he got caught.) Paid in Full restores a sense of tragic consequence to its heroes’ downfall, and many viewers will be left shaken and appalled as the film arcs its way to its conclusion. Most mainstream reviewers ignored the film upon its release, and its distributor, Miramax/Dimension, treated it as just another disposable ‘hood shoot-’em-up. But people will go on rediscovering it on video and talking about it for years to come.

— Nelson Kim

(Buy Paid in Full at Amazon.)

Pingback: HIDDEN GEMS – Summer Megamix – Hammer to Nail

Hustle Queen

This movie is a classic! Love this movie

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail