(Medicine for Melancholy has been picked up for distribution by IFC Films, who are finally releasing it on Friday, January 30th in New York City. Visit the film’s official website, or its page at IFC.com, to watch a trailer.)

Barry Jenkins’ Medicine for Melancholy arrives like a blast of fresh air in a stale, stuffy room. Part romance (or is that anti-romance?), part love letter to San Francisco (or is that hate letter?), Jenkins’ debut feature is an ambitious, thoughtful, absorbing, artistic treatise on the complicated dynamics of what it means to be a twenty-something African-American in one of America’s most gentrified cities. Aside from succeeding as a work of engaging entertainment, Medicine for Melancholy stands taller as an example of just how accomplished low-budget filmmaking can be when handled with intelligence, care, and precision. However, it is in the film’s content where Jenkins’ vision feels like a minor revolution.

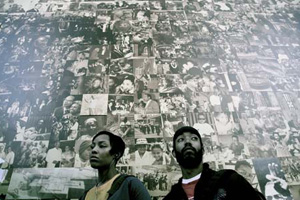

What becomes immediately apparent is the film’s striking visual sense, which is as far from the lackadaisical point-and-shoot-with-a-Handicam type of production that most low-budget filmmakers adopt out of uninspired laziness. For the determined Jenkins, on the other hand, a small crew and little money is no excuse for delivering a supremely accomplished product (this is the type of film that the John Cassavetes Award was made for). He and cinematographer James Laxton photograph San Francisco in a way that contradicts with Hollywood’s golden, sun-soaked representation of it. Their San Francisco is a city grayed by fog. When the sun appears, that is the exception—not the other way around. The world in Medicine For Melancholy is drained of almost all of its color. Instead a gray, olive pall blankets everything, reflecting the somber energy of the city, as well as expressing the passive somberness of the characters’ own individual lives. Colors do emerge, but only at certain unexpected moments, providing a visceral jolt and further conveying the protagonists’ detached, dream-like state. Added to this is an achingly shallow depth-of-field, which places us even deeper inside these characters’ minds. We grasp that they are searching for an external connection, but we feel just how heavily the city weighs down upon them. Like the city in which they live, their battle is an uphill one. On paper, Jenkins’ overtly stylistic approach might sound overblown and pretentious, but in execution, it feels completely organic and natural.

The story is a simple, but clever, one. Clearly inspired by Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Jenkins’ version twists that film’s one-night-stand premise into something original. This time, it’s a day-after-the-one-night-stand tale, where two people who barely remember the previous night’s encounter are forced to confront each other in the harsh, sober light of day. Micah (Wyatt Cenac) is a far more unsettled African-American who is struggling to hold onto his cultural identity in a city that seems uninterested in anything but itself, while Jo (Tracey Heggins) is comfortable with her immersion in the white San Francisco landscape. Both of them are fully aware that they are minorities in this metropolis—in more ways than just the obvious one—but they also understand that this is how things are. How they deal with this realization is what defines them as individuals; how they interact with one another is what gives the film its heart and soul.

The story is a simple, but clever, one. Clearly inspired by Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Jenkins’ version twists that film’s one-night-stand premise into something original. This time, it’s a day-after-the-one-night-stand tale, where two people who barely remember the previous night’s encounter are forced to confront each other in the harsh, sober light of day. Micah (Wyatt Cenac) is a far more unsettled African-American who is struggling to hold onto his cultural identity in a city that seems uninterested in anything but itself, while Jo (Tracey Heggins) is comfortable with her immersion in the white San Francisco landscape. Both of them are fully aware that they are minorities in this metropolis—in more ways than just the obvious one—but they also understand that this is how things are. How they deal with this realization is what defines them as individuals; how they interact with one another is what gives the film its heart and soul.

I can’t think of another film that so acutely addresses the multi-tiered problems inherent in gentrification from such a refreshing perspective. Even Micah, who is clearly more tormented by this predicament than Jo, cannot declare an all-out hatred for San Francisco. That’s because as much as he hates San Francisco, he is San Francisco. As black as he wants to be, he dates white girls too. How can an African-American blend so seamlessly into white culture—and feel a genuine affinity for much of that culture—yet also retain a level of “blackness” that feels untainted? Or, more importantly, is that feeling of “blackness” a limited mindset that helps to keep an individual from reaching his or her true potential? These are the unbearably heavy questions that nag at Micah, and it is his fleeting connection with Jo that leads him to believe she might be able to provide him with some answers that he might not otherwise never find.

Medicine For Melancholy is an ambitious achievement on many different levels: formally, aesthetically, dramatically, intellectually. It is destined to stand as one of 2008’s most impressive and highly accomplished low-budget dramas. Jenkins pulls off his intricate and delicate balancing act with the assurance and skill of a seasoned veteran. If this doesn’t lead to projects on a much grander financial scale, it doesn’t matter, for Jenkins has the special ability to make a film that transcends its limitations and competes with movies of the most expensive order. Medicine For Melancholy is a refreshing, vital delight.

— Michael Tully

Pingback: DVD RELEASES 2009/10/27 – Hammer to Nail