LOST HIGHWAY

(Lost Highway screens at 92YTribeca this Saturday at 7:30pm. The screening is curated by the editors of the website Not Coming to a Theater Near You. Go here for details and to purchase tickets. The film is also available on DVD in different editions, but be sure to read DVD Beaver’s comparison before purchasing.)

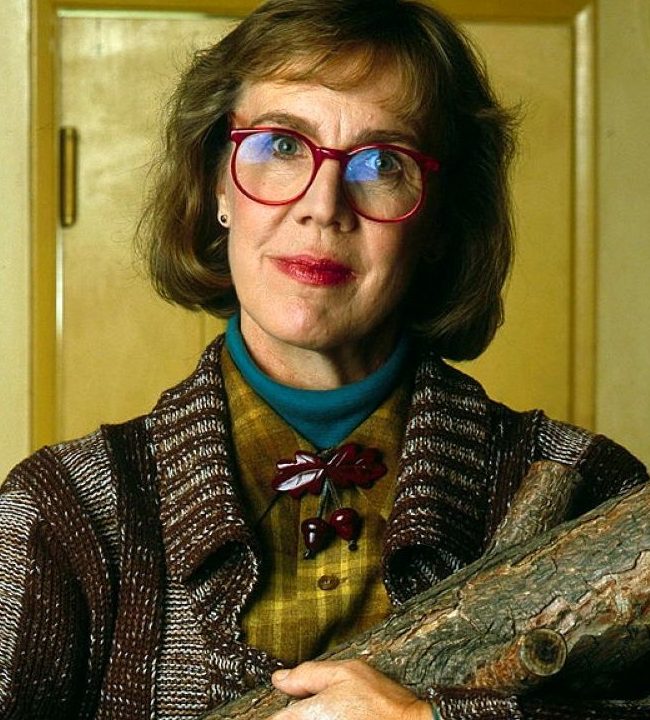

The first hour or so of Lost Highway is one of the most ravishing, indelible passages in all of David Lynch’s work. Much of it takes place in the Los Angeles house that avant-garde jazzman Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) shares with his raven-haired wife Renée (Patricia Arquette). We see everything through Fred’s overheated perceptions—fiery reds and oranges, sickly yellows—as he wanders down the hellish hallways, slowly going mad. He’s convinced Renée is cheating on him, and tormented by the thought of losing her. No one has ever filmed people moving through shadows and space in quite the way Lynch and his cinematographer Peter Deming do here. It’s like film noir pushed to the point of abstraction, with the entire house seemingly swallowed up by darkness. Skin-crawlingly weird events occur: Bad dreams. Choked screams. Videotapes arriving anonymously on the couple’s doorstep—videotapes of them, in their home. Fred’s encounter at a party with the Mystery Man (Robert Blake, unforgettable) who seems to be in two places at once.

And then, the out-of-nowhere mid-movie rupture. Following a shocking act of violence, Fred lands in prison. But after falling asleep in his prison cell, he disappears, from the cell and from the film, and is replaced by a new character and a new actor: hotshot young auto mechanic Pete Dayton, played by Balthazar Getty. The story reboots itself, apparently taking off in an entirely new direction. However, when Arquette shows up again, this time as a blond named Alice Wakefield, the realization dawns that Pete’s tale is some kind of twisted mirror image of Fred’s… This second half isn’t as densely packed with marvels as the first, but once you put the two parts together (which I, like many viewers befuddled by the film when it first appeared in 1997, was unable to do until more perceptive observers explained it to me), the genius of Lynch’s conceptual design becomes clear. I’ll refrain from offering a more detailed interpretation, since readers who haven’t yet seen the movie may prefer to try to solve the puzzle on their own—and anyway the Internet is already aswarm with in-depth analyses. I’ll just say that Lost Highway is one of the most radical reworkings of the dream-film since Caligari, and that as an exploration of doomed, damned love and a terrifying portrait of the male psyche pushed to extremes, it can stand next to Vertigo without embarrassment. Yes, it’s really that fucking good.

And then, the out-of-nowhere mid-movie rupture. Following a shocking act of violence, Fred lands in prison. But after falling asleep in his prison cell, he disappears, from the cell and from the film, and is replaced by a new character and a new actor: hotshot young auto mechanic Pete Dayton, played by Balthazar Getty. The story reboots itself, apparently taking off in an entirely new direction. However, when Arquette shows up again, this time as a blond named Alice Wakefield, the realization dawns that Pete’s tale is some kind of twisted mirror image of Fred’s… This second half isn’t as densely packed with marvels as the first, but once you put the two parts together (which I, like many viewers befuddled by the film when it first appeared in 1997, was unable to do until more perceptive observers explained it to me), the genius of Lynch’s conceptual design becomes clear. I’ll refrain from offering a more detailed interpretation, since readers who haven’t yet seen the movie may prefer to try to solve the puzzle on their own—and anyway the Internet is already aswarm with in-depth analyses. I’ll just say that Lost Highway is one of the most radical reworkings of the dream-film since Caligari, and that as an exploration of doomed, damned love and a terrifying portrait of the male psyche pushed to extremes, it can stand next to Vertigo without embarrassment. Yes, it’s really that fucking good.

A few years later, Lynch would employ a very similar story structure for Mulholland Drive, which was a box office hit, a multiple Oscar nominee, and the eventual winner of several best-film-of-the-decade polls—all richly deserved honors. But Lost Highway pointed the way. New Yorkers, don’t miss this rare chance to see it in 35mm this Saturday.

— Nelson Kim

bp

yes yes yes.

i’d love to hear that detailed explanation though.

seen multiple times and i can only speak in broad strokes

GL

Nice recap. One of the few films I saw three times in the theaters. Fingers crossed DL returns to 35mm someday!