(Keane screens Monday, February 2nd, and Tuesday, February 3rd, 2009, at the Walter Reade as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series “Mavericks and Outsiders: Positif Celebrates American Culture.” Or if you are unable to catch it on the big screen, buy the DVD at Amazon.)

Seeking redemption inside Manhattan’s Port Authority bus terminal is like bobbing for Milk Duds in a steaming septic tank. Unfortunately for William Keane, that appears to be his destiny. When we first encounter him at a point of near full-blown hysteria, Keane is stampeding through that bleak purgatorial institution accosting workers and strangers with a picture of his daughter, who was abducted several years prior. At least that’s what he says happened. Maybe that isn’t how it actually went down. Or, worse yet, maybe he was the abductor himself. For the next ninety minutes, Lodge Kerrigan manhandles our expectations and ratchets up the tension to a nearly unbearable degree, until it seems as if this story is headed for an unavoidably tragic ending. Yet, somehow, just before all hope appears to be lost, Kerrigan sideswipes viewers—as well as Keane himself—and grants an unexpected act of grace that feels all the more merciful, especially when considering the harrowing ride we’ve just been on. It makes a great film even greater.

I first saw Keane at its New York Film Festival press screening in the fall of 2004. When it ended, I knew I had watched something I would never forget. I’ve seen it several times since, but even taking that into account, it all goes back to that first devastating viewing. Nearly five years later, I am unable to go within a five-block radius of the Port Authority, or drive through the Lincoln Tunnel, without being reminded of Keane. And not just ‘reminded.’ I feel it coursing through me: the mysterious threat of danger, Keane’s frazzled, fraying nerves, New York City at its most unforgiving. Kerrigan’s psychodrama didn’t just resonate. It scarred me deeply.

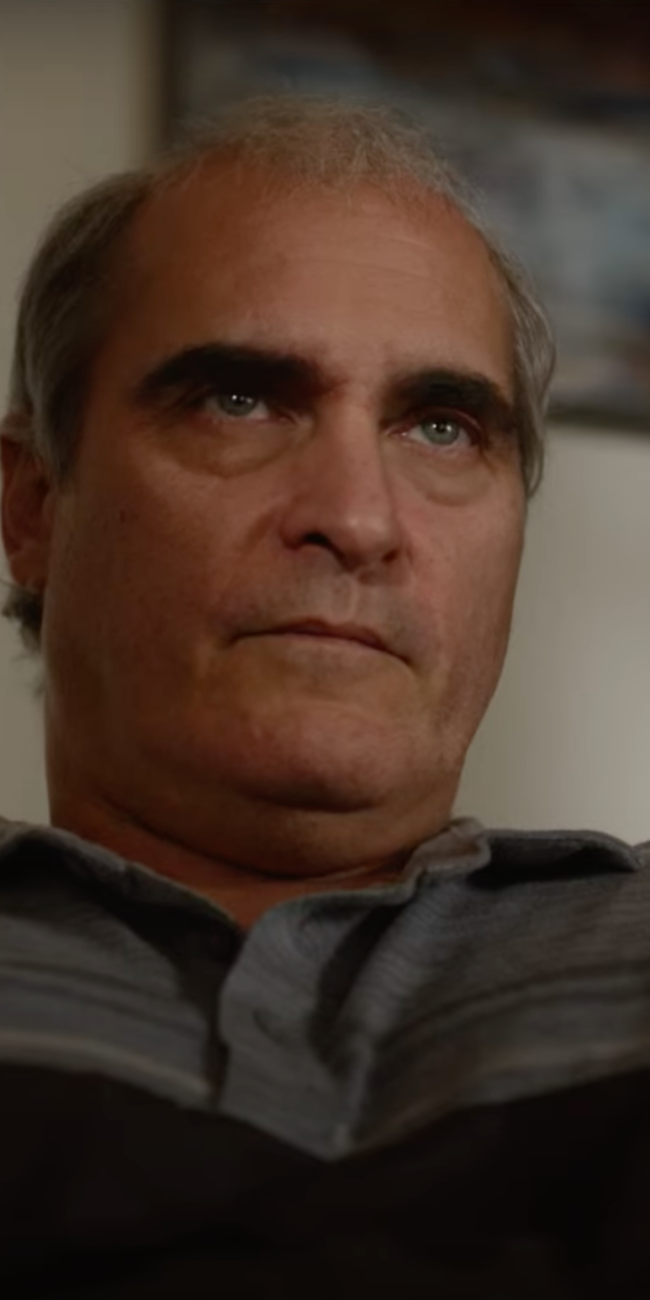

As the haunted, damaged William Keane, Damian Lewis is so convincing that it’s painful to watch (particularly in a bar scene in which the music can’t seem to get as loud as he wants). That’s a damn good thing, too, because for the film’s entire duration, John Foster’s camera is right up in his face, harassing and hounding him like the voices he hears in his head. A less commanding performance might reveal the whole production to be an artfully constructed sham, but with Lewis whispering and stammering, teetering between moments of fragile stability and full-blown mania, it becomes as shockingly real as the schizophrenic person ranting beside you on a late-night subway ride. One of Kerrigan’s main purposes with Keane appears to be forcing viewers to consider that fringe person you pass on the street and dismissively think, “That guy’s got some serious problems,” or, even more cruelly, “Thank God I’m not that dude.” But here, you can’t simply leave him in the distance by slipping around the corner. In Keane, there is no corner.

As the haunted, damaged William Keane, Damian Lewis is so convincing that it’s painful to watch (particularly in a bar scene in which the music can’t seem to get as loud as he wants). That’s a damn good thing, too, because for the film’s entire duration, John Foster’s camera is right up in his face, harassing and hounding him like the voices he hears in his head. A less commanding performance might reveal the whole production to be an artfully constructed sham, but with Lewis whispering and stammering, teetering between moments of fragile stability and full-blown mania, it becomes as shockingly real as the schizophrenic person ranting beside you on a late-night subway ride. One of Kerrigan’s main purposes with Keane appears to be forcing viewers to consider that fringe person you pass on the street and dismissively think, “That guy’s got some serious problems,” or, even more cruelly, “Thank God I’m not that dude.” But here, you can’t simply leave him in the distance by slipping around the corner. In Keane, there is no corner.

From his small but reputable oeuvre—Clean, Shaven, Claire Dolan—it’s obvious that Kerrigan is obsessed with mental illness in all its many facets. And while Keane is first and foremost the portrait of a mentally unstable man in the throes of a severely personal torment, and though it never appears to venture below Canal Street and makes no mention of the events that occurred on September 11th, 2001, I find it to be the most vital, pertinent statement about that epic tragedy that has yet been produced. Keane more accurately reflects the distraught paranoia suffered by New Yorkers in the hours and days immediately following that awful day than any film to directly address the issue. Perhaps this is reading into things too deeply. Perhaps not. But let’s leave metaphors behind in order to concentrate on more concrete ways in which Keane is a major technical achievement.

Without relying on traditional tools of the genre—a pulse pounding score, parallel storytelling, and, perhaps most importantly, the refusal to present a clear-cut goal or mission—Kerrigan revolutionizes the art of the thriller. For as the story continues to unfold, in the same way that we are straining with tension, we still have no concrete proof that any of this nerve-wracking energy is actually justified. Kerrigan uses a stripped down, hyper-immediate aesthetic not to place us inside Keane’s mind, per se, yet he nonetheless makes us feel what this troubled man is feeling. In this way, Keane accomplishes the seemingly impossible: it’s a film that one watches from the outside, with a surface level of remove, and at the exact same time, one feels it from the inside, as if it’s happening to us directly. (Note to aspiring, or even veteran, filmmakers: don’t try this at home, for you will fail.)

By introducing the characters of a hotel neighbor Lynn (Amy Ryan) and her daughter Kira (Abigail Breslin), Kerrigan provides us with a narrative strand that gives the film a more literal arc. It also enables him to more excruciatingly wrench our nerves. That Lynn lets Kira be babysat by this total stranger without grilling him seems indefensible (yet, the fact remains that Keane has exhibited no direct signs to make her worry). Later, Kira takes a shower while Keane stands nearby and lathers her up with conditioner. On another occasion, the pair goes ice-skating as another manic episode grows inside Keane (at this point, we recognize it when it’s about to arrive). Kerrigan maximizes the tension within each and every situation without feeling like he’s taunting us, further displaying his directorial maturity.

By introducing the characters of a hotel neighbor Lynn (Amy Ryan) and her daughter Kira (Abigail Breslin), Kerrigan provides us with a narrative strand that gives the film a more literal arc. It also enables him to more excruciatingly wrench our nerves. That Lynn lets Kira be babysat by this total stranger without grilling him seems indefensible (yet, the fact remains that Keane has exhibited no direct signs to make her worry). Later, Kira takes a shower while Keane stands nearby and lathers her up with conditioner. On another occasion, the pair goes ice-skating as another manic episode grows inside Keane (at this point, we recognize it when it’s about to arrive). Kerrigan maximizes the tension within each and every situation without feeling like he’s taunting us, further displaying his directorial maturity.

For all of these reasons, Keane adds up to many different movies at once, like the schizophrenic brain of William Keane himself. Kerrigan’s descent into this tormented man’s mind is unrelenting and terrifying, yet Keane isn’t just another indie film out to punish viewers. Challenge them? Yes. Frighten them? Yes again. But with his film’s merciful resolution, the nobility of Kerrigan’s mission reveals itself. Keane is a riveting tour-de-force of American independent filmmaking.

(One final, perhaps superfluous point that I can’t help but acknowledge: the thought of unsuspecting Netflixers ordering this movie based on the cast of now familiar faces—Lewis, Ryan, and especially Breslin—who were relative unknowns when the film was made but have now become household faces [if not names]. Oh, how sickeningly sweet a thought that is!)

— Michael Tully