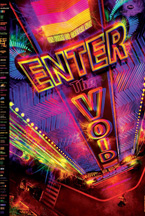

ENTER THE VOID

(Enter the Void opens tomorrow in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, with more cities to follow. It will also be available through IFC’s video on demand platform on September 29.)

Warning: This review contains plot spoilers.

Our main character gets shot in a drug bust and dies less than a third of the way through the movie. But that’s not the spoiler. The spoiler is that an instant later, he comes back—not his body, but his soul or spirit. And the rest of Enter the Void will be about his soul’s journey toward the next stage of existence.

The map of that journey is laid out in the film’s early scenes: Oscar (Nathaniel Brown), a young American expat and drug dealer in Tokyo, is reading a copy of the Tibetan Book of the Dead that he borrowed from his artist friend Alex (Cyril Roy). Alex accompanies Oscar on what will turn out to be his final, fatal transaction, and on the way explains the Book’s vision of the afterlife—how the soul must pass through a succession of challenges in order to achieve either liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth, or instead begin its next earthly incarnation.

And once Oscar dies, his soul embarks on a similar odyssey. In life, Oscar was devoted to his wild-child younger sister, Linda (Paz de la Huerta), who had recently moved to Japan to reunite with him. Now, in death, he relives key memories from his past—the car crash that killed his and Linda’s parents, the vow he made to always protect her, the state-mandated separation that kept them apart as they grew to adulthood. His soul can’t continue on its way until he’s sure that Linda will be alright without him, yet he can no longer interfere in corporeal affairs. So he flies above Tokyo, a benevolent but powerless ghost, hovering over his sister and waiting for her to be delivered to safety.

And once Oscar dies, his soul embarks on a similar odyssey. In life, Oscar was devoted to his wild-child younger sister, Linda (Paz de la Huerta), who had recently moved to Japan to reunite with him. Now, in death, he relives key memories from his past—the car crash that killed his and Linda’s parents, the vow he made to always protect her, the state-mandated separation that kept them apart as they grew to adulthood. His soul can’t continue on its way until he’s sure that Linda will be alright without him, yet he can no longer interfere in corporeal affairs. So he flies above Tokyo, a benevolent but powerless ghost, hovering over his sister and waiting for her to be delivered to safety.

Gaspar Noé’s first two features, I Stand Alone and Irreversible, combined transgressive shock tactics with tricky narrative structures and aggressively baroque (and highly accomplished) technique. Enter the Void scales back somewhat on the sex and violence, but in all other respects it’s Noé’s boldest movie yet. He goes for maximum sensory overload in every moment of every scene, bombarding the viewer with lens-and-light effects, swirling CGI psychedelia, swamp-dense sound design, and above all, stunningly virtuosic camerawork. Nearly the entire film is shot from Oscar’s point of view. In the opening scenes, the camera sees only what he sees; once the flashbacks kick in, the perspective expands slightly, filming from behind him as if he’s watching a movie of his own life. But in the film’s last and longest movement, as Oscar’s soul leaves its body and flies into the air, the camera goes with it, and the rest of the story’s running time is one long, delirious series of digitally enhanced crane and dolly shots that send us floating through walls and ceilings, soaring over the rooftops of Tokyo, diving straight into an ashtray or an airplane or someone’s brain. If there really is an afterlife, F.W. Murnau and Alfred Hitchcock are probably applauding.

The film is, perhaps, too long and too repetitive: nearly every stylistic device and technical flourish wears out its welcome as the story lumbers into its second, then third hour. Even as Noé ups the ante on the outrageous imagery (look, now we’re entering the mind of an aborted fetus! Now we’re inside a sex hotel, and—whoops, whose vagina is this?) and moves Enter the Void toward its 2001-inspired cosmic conclusion, I found myself desensitized, and impatient for it to end. The movie could, by my reckoning, stand to lose a good thirty minutes or more. But that would still leave us with close to two hours of visionary, enraptured cinema, a grand and generous gift from a director hell-bent on pushing the limits of mainstream filmmaking. To complain that he goes too far would seem to be beside the point.

Some viewers are bound to argue that Enter the Void is a triumph of style over substance, that its ideas about death and transcendence are ultimately sophomoric. I mean that last adjective literally: at its worst, watching the film is like being trapped in a dorm room with a nineteen-year-old tripping on ‘shrooms for the first time—who is convinced that he has unlocked the secrets of the universe, and is going to keep you up all goddamn night telling you about it. More importantly, though, at its best, the movie makes you feel like you’re a nineteen-year-old on ‘shrooms, rewiring your perceptions of the visible world, making mad connections that draw together the disparate strands of consciousness into a bright pulsating unity. To go all the way with Enter the Void, you pretty much have to be willing to check your mind at the door—its “philosophy,” if it can be called that, hardly stands up to rational scrutiny. But if you’re open to what the movie has to offer, it will make your senses sing. With any luck, actual nineteen-year-olds will find their way to it in large numbers—this is the kind of work that can convert young people into cinephiles for life.

Some viewers are bound to argue that Enter the Void is a triumph of style over substance, that its ideas about death and transcendence are ultimately sophomoric. I mean that last adjective literally: at its worst, watching the film is like being trapped in a dorm room with a nineteen-year-old tripping on ‘shrooms for the first time—who is convinced that he has unlocked the secrets of the universe, and is going to keep you up all goddamn night telling you about it. More importantly, though, at its best, the movie makes you feel like you’re a nineteen-year-old on ‘shrooms, rewiring your perceptions of the visible world, making mad connections that draw together the disparate strands of consciousness into a bright pulsating unity. To go all the way with Enter the Void, you pretty much have to be willing to check your mind at the door—its “philosophy,” if it can be called that, hardly stands up to rational scrutiny. But if you’re open to what the movie has to offer, it will make your senses sing. With any luck, actual nineteen-year-olds will find their way to it in large numbers—this is the kind of work that can convert young people into cinephiles for life.

— Nelson Kim