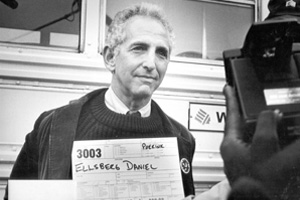

MOST DANGEROUS MAN IN AMERICA: DANIEL ELLSBERG AND THE PENTAGON PAPERS, THE

(***The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers is streaming for free online at PBS’s POV website from October 6-27, 2010.*** It world premiered at the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival and opened theatrically in New York on September 16, 2009, at the Film Forum.)

The dilemma of professional honor versus patriotism gets a hearty workout in Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith’s The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. Whatever one thinks about Ellsberg’s decision as a governmental insider to go public with classified documents in 1971 regarding the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam conflict, one cannot deny that few Americans have ever been forced into such a moral and ethical quandary as Ellsberg.

Or have they? Gradually, over the course of the film, as Ellsberg himself recounts the story of our country’s troubling history with Vietnam, the current situation in Iraq becomes more than just a mere parallel; it becomes a mirror image. And if one makes that virtually unavoidable connection, a more disturbing question emerges: why hasn’t this behavior happened more often, throughout the course of history?

Is it because Ellsberg’s actions are, like his opponents say, those of a criminal, a liar, a traitor? Was his professional vow of silence with regards to his immediate superiors, and, by extension, the institution to which he belonged, more important than his overwhelming sense of duty to his fellow Americans, as well as those innocent civilians in Vietnam? This is a question that Ehrlich and Goldsmith don’t address directly, but by simply allowing Ellsberg to tell his own story, they make a powerful argument in support of the man, and deliver a rousing call for others to join him.

Let it be known that Ellsberg wasn’t some hippy outsider who infiltrated the government with a master plan of exposing its deadly corruption. No, he was a believer—in his government, in his profession, in his support of America’s involvement in Vietnam. So much so, in fact, that in 1964, as Special Assistant to Assistant Secretary of Defense (International Security Affairs), he was responsible for producing a report on Vietcong atrocities that enabled Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to begin bombing North Vietnam.

Let it be known that Ellsberg wasn’t some hippy outsider who infiltrated the government with a master plan of exposing its deadly corruption. No, he was a believer—in his government, in his profession, in his support of America’s involvement in Vietnam. So much so, in fact, that in 1964, as Special Assistant to Assistant Secretary of Defense (International Security Affairs), he was responsible for producing a report on Vietcong atrocities that enabled Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to begin bombing North Vietnam.

It wasn’t until later that Ellsberg realized the gravity of his actions, which hadn’t at that time been supported by concrete facts. By that point, the Vietnam War had spun all the way out of control and Ellsberg was now working for the RAND Corporation on the “Pentagon Papers,” which studied U.S. decision making in Vietnam from 1945 through 1968. As he learned more and more about his government’s devious actions, no matter the president, his own role in the fiasco began to take a toll on him. In order to redeem himself, he felt a dramatic measure must be taken. He wanted his fellow countrymen to see this report.

Ellsberg narrates his own story with intelligence, grace, and passion. This was a wise decision on the filmmakers’ part, as it personalizes the situation for viewers who might not be sympathetic to Ellsberg’s plight from afar. I’ve always felt that it’s better to hear an anti-war argument from someone who fought on the frontlines, or that it’s better to be warned of the dangers of drug and alcohol abuse by an addict. Ellsberg wasn’t just there. His hands are dirty. By telling his story in this way, it has the potential to appeal to those detractors who would love to render a “traitor” verdict before the trial had even started.

As for the filmmaking itself, Ehrlich and Goldsmith employ the dreaded—to me, at least—technique of the “Hollywood thriller recreation,” to enhance the tension of certain scenes. The problem is that this technique itself automatically reduces the tension since it feels like such a forced stylistic choice. Let’s hope I’m in the minority on this one. That said, they don’t overuse it, instead relying on stock images, footage, and Ellsberg himself to build the tension.

While The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers might not break any formal ground, it nonetheless feels like a vital time for this story to be told. And—recreations aside—Ellsberg and the filmmakers tell it very well.

— Michael Tully