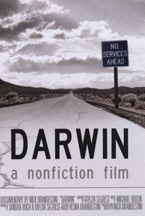

(Darwin world premiered at the 2011 Santa Barbara International Film Festival. As a selection in the DocuWeeks 2011 program, it opens theatrically in New York City at the IFC Center on Friday, August 12th, and in Los Angeles at Laemmle’s Sunset 5 on Friday, August 19th. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

Darwin is the kind of movie that really shouldn’t work—the bulk of it is nothing more than interviews with retirees living quietly and without much conflict out in the California desert. But slowly and deliberately, it gets under your skin. Watching it is like reading the epilogue of a great novel and getting tantalizing clues to the great adventures and tragedies that came before.

The town of Darwin has a violent, Wild West history—it was a mining town with a reputation for lawlessness and murder. There’s never been a church. When the mining operation closed down for good in ’77 a lot of counterculture types moved in, but today there are only 35 people living there, sharing a fragile source of water that comes from inside the nearby top-secret military base. They mostly live on some kind of government assistance. “Wild horses couldn’t drag me outta Darwin,” says Susan, the town’s flinty postmaster. “I got the best job, regardless of, you know, it’s the only job.”

One of the few people left from the mining days is Monty, whose first wife Lucky was killed in a fight by a woman who was never prosecuted for the crime. A bullet from Lucky’s gun is still lodged in the ceiling of the house where they used to live—she drunkenly shot the end of her finger off while giving a bald friend “a haircut” with a bullet. But there seems to be even a lot more to Monty’s story. “It was rough to raise children,” he says. “This was no town to raise kids in. That’s one thing we don’t talk about too much.”

Darwin gradually comes into focus as a place where people can take their sorrow, shame, or disgust and just be as far away from the world as possible. Spunky seniors Hank and Connie come across as warm and generous spirits, but skeletons emerge from their closet too. They take a day trip to Barker Ranch, where Charles Manson was arrested. “Charles Manson—well, he was definitely strange, maybe even nuts…” says Connie. “I have mixed feelings about Charlie Manson.” “Charlie Manson was a piece of shit, and still is,” interrupts Hank. “Yes, I met him.” Connie is not so sure: “Well, but…”

Darwin gradually comes into focus as a place where people can take their sorrow, shame, or disgust and just be as far away from the world as possible. Spunky seniors Hank and Connie come across as warm and generous spirits, but skeletons emerge from their closet too. They take a day trip to Barker Ranch, where Charles Manson was arrested. “Charles Manson—well, he was definitely strange, maybe even nuts…” says Connie. “I have mixed feelings about Charlie Manson.” “Charlie Manson was a piece of shit, and still is,” interrupts Hank. “Yes, I met him.” Connie is not so sure: “Well, but…”

Hank’s transgendered son Ryal and his girlfriend Penny are seemingly the only young people in town, and for them Darwin is a place to regroup and develop a stronger sense of self after an experience of being spat out by society. Here the film demonstrates the healing qualities of a place where, in Hank’s words, people “accept you for who you are today, not what you used to be, not what you might be.”

Outside Monty’s front door there’s a statue of Buddha that, we’re told, got scratched up in a knife fight. Director Nick Brandestini has a great eye for such visual signifiers. A U.S. Post Office decal cracked into a million fragments by the beating sun; a close-up of a few paperbacks on offer in the makeshift town library—Jaws and something with a swastika on the back cover. The visual style of the film is inventive without being showy—Brandestini’s camera angles and compositions pop with a subtly playful energy.

The editing is inspired, creating dialogues between separate interviews and achieving a rhythm that nicely expresses the meditative, non-linear spirit of the town.

The name Darwin brings up the idea of the state of human evolution, or potential to evolve. Many of the characters have come a long way from surviving on raw instinct and violence to finding a degree of compassion and self-acceptance, finding the best in themselves. Monty is revealed to be an astonishingly talented visual artist. In another sense the town could be seen as what’s left of the human spirit—pushed to a remote outpost with barely enough water, up against a base where they test out weapons that could potentially destroy the world.

But this is far from a political film. Darwin is structured to give you an organic sense of slowly getting to know its characters: eventually all sorts of dark secrets and buried sorrows work their way to the surface, and the film builds to a thoroughly earned emotional catharsis. Brandestini has created a work of quiet power, earning the trust of an eccentric, introverted town, and coaxing forward its mysteries and strange beauty.

—Paul Sbrizzi

Karen Arnold

I have not seen this show, but it brings back some memories. I remember moving to Darwin the summer before I entered 4th grade. There was no electricity in my house and there was a rain storm that summer. I rode 42 miles to go to school in Lone Pine, I don’t remember our P.O. Box #, but it was in the old one that is doarded up now. I remember the Bar that my dad went to, I learned hoe to play pool by standing on milk crates, I learned how to drive on the old Air Strip and around the cemetary. I remember going to a house once a week to watch TV which had a lot of static and John and Shirley Moody’s gas station. Going hiking and in and out of old mines was a fun time. When I lived there, there were 52 people counting the kids whether or not they were in school. My Pop died while I lived there. When will this be on TV? I would love to see what some people think of Darwin. I still, for some reason think of it as home. – – Karen