THE CURBSIDE CRITERION: MIRROR

Does the average moviegoer in 2021 have the eyes, the ears, the temperament, the patience, or even the vulnerability necessary to allow a master like Tarkovsky to take them on a poetic and autobiographical journey? The obvious answer is no. We do have empirical evidence to back this assertion – box offices invariably show mass marketed slop, rehashed formulas, and infantilized scripts at the top. Then there is the more anecdotal evidence for this assertion which, in my opinion, is just as powerful.

I have heard many film consumers both in my personal life and on the media comment that they cannot wait to return to a state of pre-pandemic normalcy in which they can once again enjoy their big budget rubbish in cineplexes – the world has changed post-Covid but not the average moviegoer’s taste for comforting communal hyperstimulation. I have also heard many say that after a long busy day, a poetic film that defies easy dissection and interpretation is too tiring of a mental exercise. Now, let us be fair. Tarkovsky’s film are challenging. But perhaps here, in the notion of the “busy,” we can find an interpretative crowbar that may loosen the enigmas contained in Tarkovsky’s work.

Mirror can be rightfully acknowledged as Tarkovsky’s most autobiographical film. It explores the realm of personal memory. Mirror’s structure mimics the workings of memory – its chronological inconsistencies, memory’s reliance on specific details out of which narratives are formed, its distortions, its ultimate undecipherability. Memory requires introspection, time alone, freedom for consciousness to ramble in its own unpredictable way. When we are busy, we are pulled away from introspection and entangled by duties, expectations, trivialities, stressors, opinions, roles. In short, our internal poetry, our memories, are smothered by the outside world, by others, by an inauthentic way of being that Heidegger called “the they.”

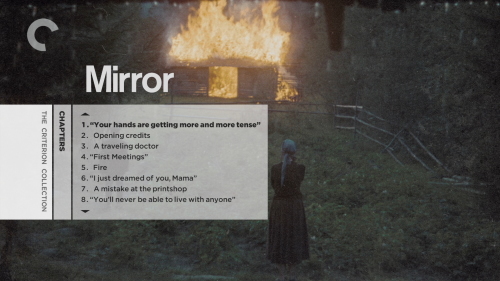

Mirror plunges us into the internal, the personal, away from the hurly-burly of the busy world. There is a tradition in literature of these plunges into memory being connected to the senses – in the case of Proust, the taste of a Madeleine cookie. In Mirror, Tarkovsky’s alter-ego, Alexsei, has memories that revolve around an array of sensual perceptions – the visual of the delicate hairs on the nape of a woman; heat marks on a table; wind rustling the leaves on a tree, tilting blades of grass, running through the hairs on our bodies. Voices emanate from the corridors of a country house that we suspect Alexei ran through as a child. Each room in the country house seems impregnated with specters and voices which touch off more memories, which touch off others, and so on. And as with every Tarkovsky film, fire and water play key visual roles. And aren’t these elements the ultimate metaphors for memory? Just like fire, memory is a phenomenon made up of primary elements coming together, it is sparked, it is irreducible. In the case of water, the metaphor is even more historically obvious. Memory takes place within consciousness which has been described as a stream.

It should be noted, however, that Tarkovsky does not erase the outside world and its impact on memory. In one sequence of Mirror, Alexsei’s mother (Margarita Terekhova) gets entangled in the busyness of work. She works in a printing house. She stresses over a misprint, one that will be certainly interpreted, she feels, as “obscene” – a picture of Stalin in the office makes it clear to the viewer why she is so stressed over this misprint. It is precisely these workplace dramas that take us away from introspection, that eat away at our internal poetry. But herein lies Tarkovsky’s genius: even the hurly-burly of busy existence interacts with personal memory and is incorporated into it. Even historical events, though outside of us, get interwoven with personal memory – Tarkovsky uses actual WWII footage, footage of the Spanish Civil War, bullfighting, atom bomb explosions, and Maoists holding the Little Red Book up to the camera.

Mirror’s visual and narrative power have been enhanced by the Criterion Collection’s new 2k digital restoration. The audio has also been polished. This Blu-Ray edition transforms – ironically enough – what is a very abstract narrative, into a visually realistic and almost 3-D film. The clarity of the images makes the viewer virtually feel the wind upon the hairs of their arms. When a character looks straight into the camera, for a second, one feels as though they are going to climb out of the screen and onto your living room.

Having recently rewatched Malick’s The Tree of Life, I cannot help but find thematic similarities between it and Mirror. Both movies obviously deal with memory, specifically childhood memory. This time around, however, I was much more attuned to Brad Pitt’s and Sean Penn’s characters within The Tree of Life’s narrative. Both characters are caught in the busyness of their careers. In the case of the Brad Pitt character, his job defines his identity. In the case of the Sean Penn character, he feels an emptiness, a malaise, an inauthenticity, in the everyday concerns of his career. There is a reappraisal of life, a search for meaning, in the childhood memories of the Sean Penn character. If we take Mirror’s message seriously, perhaps Tarkovsky was more revolutionary than the Soviet state and the culture ministry bureaucrats that branded his work as too “individualistic” or “idiosyncratic.” One is reminded of the Bertolt Brecht quote: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.” Tarkovsky makes us question the trivialities and stressors of work, duty, and how these things that pass as the “real” world asphyxiate our poetic introspective lives. If introspection is needed for memory, if we all need a space wherein we can find breathing room for our poetic humanity, then perhaps we need to reshape that which keeps us busy and inauthentic – work.

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13)