(Boy Meets Girl is now showing at Film Forum through Thursday, August 14, 2014, via Carlotta Films. Richard Brody will be intro-ing the 7:30pm show on Monday night the 11th]. It is also available on home video if you do some digging.)

The first time I saw Boy Meets Girl, it was a copy that said “subbed version” on VHS. Boy. Was it subbed. The English titles at the bottom were only half on the screen. It made me so frustrated (I don’t really speak French) I almost turned the fucking thing off.

But I didn’t. I kept right on watching. Something was drawing me in. I felt like I was walking underwater. That wasn’t all that was off about the tape. The voice that comes in right away in the beginning sounded slowed down. The whole thing felt like an artifact. A relic. It felt like it had been waterlogged. I was sure, again, that something must be wrong. Then I realized, this was no mistake. This was how Leos Carax wanted these words to be heard: slowed down, played out, still.

And like that, he had me.

Here we are all alone

It is all so slow

so heavy

so sad

soon I

will be

old

& it will

at last…

be over.

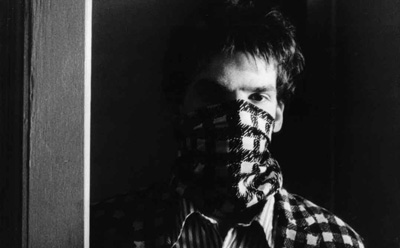

These words draw slowly out over images of the river. We meet a young mother fleeing the father of the little girl perched in her lap behind the wheel of their car as she drives along the water. She phones the father, rehearsing her speech while the little girl listens on. She tells him they’re finished, that she’ll throw the paintings in the river. She leaves the phone off the hook so he can hear the splash when she throws them in. She runs down the harbor wall to a young man playing with prayer beads. Asks the date. He tells her, she drops a scarf on the way back to the car. The young man picks it up. As he bends down, he hears a voice call his name, and turns. So we meet the bearer of that voice, Alex (Denis Lavant). Alex, our Invisible Man.

Alex and Thomas, the young man with the scarf, walk along the water. Alex tells Thomas of his great lost love, Florence. How he knows it was his closest friend who she’s run off to. A moment of sudden violence later and the two of them are on the ground, with Alex choking the life from Thomas, who wriggles somewhat helplessly despite his ample advantage in size. The whole thing seems to occur in slow motion, but plays at normal speed. Rather it is the silence in which it takes place that seems to provide for the languorous weight hanging over everything, like an ether dream, or a reenactment. As Thomas tries to open his knife, one-two-three too many seconds pass in utter anxiety for the eye of the audience, until he drops it lifelessly, seemingly strangled. That’s crazy, Alex says to himself. He grabs the scarf the young mother had dropped out of Thomas’ pocket. It is the same pattern as his jacket. Florence’s, he tells himself. This is our introduction. This is all we know of this slight, lithe young man with a way of darkness to his gait and the spring of play in his steps. Alex.

Alex and Thomas, the young man with the scarf, walk along the water. Alex tells Thomas of his great lost love, Florence. How he knows it was his closest friend who she’s run off to. A moment of sudden violence later and the two of them are on the ground, with Alex choking the life from Thomas, who wriggles somewhat helplessly despite his ample advantage in size. The whole thing seems to occur in slow motion, but plays at normal speed. Rather it is the silence in which it takes place that seems to provide for the languorous weight hanging over everything, like an ether dream, or a reenactment. As Thomas tries to open his knife, one-two-three too many seconds pass in utter anxiety for the eye of the audience, until he drops it lifelessly, seemingly strangled. That’s crazy, Alex says to himself. He grabs the scarf the young mother had dropped out of Thomas’ pocket. It is the same pattern as his jacket. Florence’s, he tells himself. This is our introduction. This is all we know of this slight, lithe young man with a way of darkness to his gait and the spring of play in his steps. Alex.

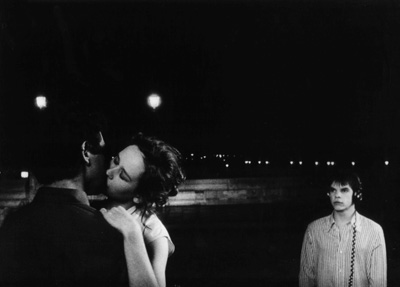

Carax (nee Dupont) needs no better introduction to any of us than this man. This passage of time for fools through the prism of a magician. He is the kind of man who can stroll past two lovers embraced (on a bridge no less) and not even a wisp of attention be paid. He is the kind of man who can listen in on the most public kind of violated privacy between two lovers, a rejection via tenement intercom. He is the kind of man who can summon a deaf man at a party to launch into a sign-language + interpreted tirade on how the youth are too silent, on how things were better once the “talkies” began, on how he was one of the first grips…

I draw the parallel because the parallel begs to be drawn. Flash forward, to a scene from Mauvais Sang. Second chapter: A different Alex, with the same face. That same darkness washed over him, that blank look of a secret keeper. The young man before us is no longer of this world. He is forgotten by all, disappeared from this level plane. He is off the map. The territories we go through now with him are uncharted, as they are staged—they are an artifice as love is in the same. The pursuit of love, lost, forgotten, or yet to be claimed, this is as strange a pursuit as that of a story—we can no more name the perfect tale, craft the narrative to hold the eye and ear for all the ages any better than we can bottle and sell affection, devotion, and lust in a modified concept.

Again, a scene. This Alex makes a call. On the other end, another, different Thomas.

Alex: Thomas?

Oui.

No, I didn’t listen to the messages.

I don’t want to know.

Yes, an orphan at last.

No, I’m leaving Paris without a trace.

I wake up with a belly of cement.

Yes, it’s been like that ever since that place.

This Alex then leaves Thomas his books and his girl, Lise. This can’t be the same young, frightened man. This Alex seems drawn to another woman’s arms, to another world of intrigue, and feels the need to run this time. He feels the need to flee, but also to make right perhaps what he left in the past, what he laid to waste within his previous wake. And run he does, captured in a sequence so iconic now for its use of music and a single, deliberate tracking shot, it is recognized by many, including those who don’t realize it’s from a greater film.

Alex again sneaks out into the night. “Modern Love” begins to play. His steps along the cobblestone sidewalk, broken and jagged, alongside a Paris neighborhood wall, covered in tattered posters and shuttered windows, become increasingly erratic, frenzied in their pace. His staggered walk turns into a run. He breaks out, clutching his abdomen as if in a sudden, sharp pain. This Alex runs from the love he pursues in such a stupor of innocence in the first chapter of our time with him. He runs from Lise. He doesn’t love her enough to not give her away. He flees her because in this world, this same world of artifice and introversion, to lust without love can be fatal. This Alex’s clutch turns into self-harm. He does not run with such abandon out of pain. He runs to act out in harm unto himself, for something worthy of his own spite that we can never know. For that darkness we’ve seen washed over him from the beginning.

His run turns into a compulsive routine, complete with cartwheels, arabesque leaps, slight stumbles here and there. He lags slightly at times, only to recover with the seemingly magical grace of the acrobat, somehow infallible. It is a subjective following sequence of remarkable grace and unity between the camera and the performer, a moment of truly profound choreography. He seems imbibed with a spirit of reckless, willful disregard for his own being, and blessed with new strength. What has happened since last we left him, since we first met? This Alex isn’t the Alex who seemed so ready to give up that he had lost all ability to call any attention to himself by the time we first had our introduction. That Alex had grown so pale, the world around him appeared like black-and-white TV with the sound turned off. He had grown so pale as to become invisible. This one seems to have found someone new he can project his desire upon, perhaps just as every one of his girls, his loves, could be the same person with a different name. So he can tell himself he flees from fate, from danger, from the risk of hurting someone beautiful, out of compulsion to run and not from some guilt that is bound to become visible by the time the tale is told through.

He hasn’t been the same since that place. Does he mean by the water that night? Does he mean in our first time out with him, by that point convinced of his paranoid rage by the misconception that Florence had given the scarf to Thomas? So clouded over with rage. with love, one and the same. Could he have meant outside Thomas’ flat where he leaves a bag of records stolen for Florence? It is the theft of these records that occurs in broad daylight that only further speaks to his invisibility, as he runs left out of the record store with scores in hand, having jettisoned the idea of hiding his crime once his efforts at concealment fail. He is followed closely by the shopkeeper, who for some reason turns right and never looks back. It’s because he doesn’t see what we do. Frustration and love have battered this young man until he is transparent. Like water in the sink. Like a ghost.

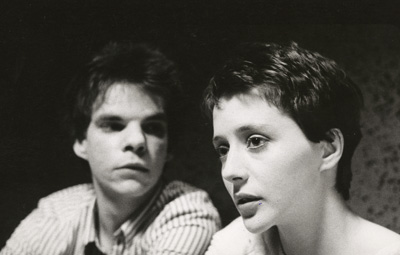

From this moment forward, we follow this young man, with few exceptions, through an arcade of vignetted glimpses into other people’s lives, and fleeting glances at one beautiful stranger’s vulnerable little heart. When finally, as the title would suggest is the cornerstone moment of the piece, Boy Meets Girl—it is something that seems to have happened a myriad of times already. So when it comes, we know what’s coming. We are used to it by now, the dangerous malaise that seems to flow over everything here. As Alex circles and encloses upon the object of an obsession he seems driven to fulfill, Mireille, a girl he meets only vicariously through her erstwhile lover’s seeming indifference towards her, we come to realize that the world around him is an unreliable one, like a narrative, or a play, with stops and starts, black leader where no space should be, with different iterations of the same words, over and over, different reactions to the same questions, or the same silence. Different takes. So when they finally do, we seem to have accepted the futility of his search for some idyllic picture of love, we seem to no longer be intrigued by what happens after the inevitable meeting of girl and boy. We no longer need him to meet her. For he has met her, he has always been acquainted with her, for as long as we’ve know him. As long as we’ve all known each other.

From this moment forward, we follow this young man, with few exceptions, through an arcade of vignetted glimpses into other people’s lives, and fleeting glances at one beautiful stranger’s vulnerable little heart. When finally, as the title would suggest is the cornerstone moment of the piece, Boy Meets Girl—it is something that seems to have happened a myriad of times already. So when it comes, we know what’s coming. We are used to it by now, the dangerous malaise that seems to flow over everything here. As Alex circles and encloses upon the object of an obsession he seems driven to fulfill, Mireille, a girl he meets only vicariously through her erstwhile lover’s seeming indifference towards her, we come to realize that the world around him is an unreliable one, like a narrative, or a play, with stops and starts, black leader where no space should be, with different iterations of the same words, over and over, different reactions to the same questions, or the same silence. Different takes. So when they finally do, we seem to have accepted the futility of his search for some idyllic picture of love, we seem to no longer be intrigued by what happens after the inevitable meeting of girl and boy. We no longer need him to meet her. For he has met her, he has always been acquainted with her, for as long as we’ve know him. As long as we’ve all known each other.

The injured (not strangled) man wakes up. Alex rushes him and throws him into the river.

Wait a second. Isn’t this the story of stories? Just one about boy meets girl? No. This is about storytelling after all, about performance, and how we perform for each other. And what better story than that of Prince Valiant or Charming sweeping his bride off her feet to quell our suspicions that something is rotten along the Seine? What better move than to light our fuse and run for the hope that we might realize—there is no boy meets girl, not anymore. Nothing is so simple. Nothing is only in one take.

Alex is everywhere. He appears to move unnoticed. He moves among the wreckage of the city of lights at night, amidst the deathtrip of the banal, lives in turmoil all around him, like a spirit drifting anonymous, an apparition whose presence is only felt by us in the dark of our seats before the screen. Yes, Mireille dances for no one in the quietude of her empty apartment, Bernard having left her once again. Yes, she dances for herself. Yet she also dances for us. We are the divining rod by which this world be judged. Our eyes. Like Alex, who can invade the most intimate or private moments and conversations of the strangers he encounters, and yet never be taken in and accepted as another member of the scene, of the communion nearly everyone else in the world seems to be engaged in, she seems to drift in and out of the waking world, on the tail end of a dream. Both of them seem to have emerged from some land absent from time, disoriented, confused, guarded, quiet after crashing back into this realm, freshly submerged in the chaos contained herein. It is a startling sight.

Flash forward to the third chapter Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, and we see the extremity of it. In this incarnation, Alex has dredged himself deep into the lot of indigence, retreated to the margin completely. He is killing himself, desecrating his body, slowly. Drunkenly. And all of it for what? For something we can only imagine, something we can only imagine is Florence, Mireille, Lise, Anna, all of them. If he’s so deserved of this torture, if he’s so guilty, this must be the same person. This must be the same Alex after all.

When the Boy in Boy Meets Girl finally gets to meet that Girl, he lives the moment over and over; every revision in his mind, every different retelling of it, every possible permutation, plays out before our very eyes. We have the sole window in. Everything that’s true or untrue about this wandering, drunk and damaged creature who we will follow through three different worlds and stories, three different versions of the same conceited pursuit, everything he wants us to see about himself, everything he lets us see, what he will decide we can know, he does for us. Specifically. He does it right in front of us, making no effort to shield himself or shy away. He does not cover himself, appears to have nothing to hide.

But with Alex, though invisible in one way or elusive in another, impossible to capture or pin down, we are the exclusive audience to his crimes, his pain, his struggles. We have an eye that only opens to how nothing is hidden with this Invisible Man. It’s as if he is viewing the different dailies of the movie of his life that’s playing in his head and he’s acting out the different sketches he wishes to keep in the story, trying to get it right. Trying to tell it in a way that’s the same as the last version but somehow better. As if we’re a part of his editing process. As if we’re watching his dream as he dreams it. We learn here that Alex wants to make films. Somehow, this fever is beginning to make sense. Alex doesn’t know what he wants. He thinks he knows what love is, what it was that was lost to him, what his obsession truly cares for. But although we will follow and at times be shocked by him, there is no judgement to this Boy’s choices. We see him naked as he is, drunk and damaged. His delusions (i.e., dreams of how things could be) keep him going, and seem to engage the world in battle for dominance, for a return to the vibrant color and romance of his dreams’ origins. The Oz to the Kansas of his muted reality.

But with Alex, though invisible in one way or elusive in another, impossible to capture or pin down, we are the exclusive audience to his crimes, his pain, his struggles. We have an eye that only opens to how nothing is hidden with this Invisible Man. It’s as if he is viewing the different dailies of the movie of his life that’s playing in his head and he’s acting out the different sketches he wishes to keep in the story, trying to get it right. Trying to tell it in a way that’s the same as the last version but somehow better. As if we’re a part of his editing process. As if we’re watching his dream as he dreams it. We learn here that Alex wants to make films. Somehow, this fever is beginning to make sense. Alex doesn’t know what he wants. He thinks he knows what love is, what it was that was lost to him, what his obsession truly cares for. But although we will follow and at times be shocked by him, there is no judgement to this Boy’s choices. We see him naked as he is, drunk and damaged. His delusions (i.e., dreams of how things could be) keep him going, and seem to engage the world in battle for dominance, for a return to the vibrant color and romance of his dreams’ origins. The Oz to the Kansas of his muted reality.

By the closing moments, we realize what this story is. It’s the beginning of something, more than anything. It’s about someone searching for someone who can remind him of the need to protect himself, someone he can protect. Someone to live for. It’s about the dread of not knowing that person’s name, or knowing their name but never knowing them, or meeting them a million times and never getting it right. Never saying it the way He wants to, no matter how many chances He has to say it. Never making it happen the way it happens in his dream. Just different takes, every time. He loses focus, he becomes soft, he fades, until the world no longer recognizes him, never seems even close to acknowledging his presence, no matter how close he may be. He is the Invisible Man, black-and-white, silent, hurtling through space on a mad dash to save someone or offer up some similar sacrifice of his own flesh and pain, if only it will help. This is someone who will suffer and still has a long way to go.

In the horror of being too late to stop the self-infliction, he may recognize in the new worlds and women upon his horizon, of being not only unable to change his story, to craft it as one would a story, but also the catalyst for which a love may die. Perhaps it is there we find the answer, the place from which he was driven out of, which keeps his descent into madness steady and drives him on across the three known chapters in the chronicle that is the Invisible Carax. The man behind the curtain, behind the scenes, behind the camera, at the secret passage, leading us onto a balcony in a dark theater, the same vantage given at our window into him, into his surrogate stand-in’s trials and trails. The Story, Himself—hiding somewhere in the story, somewhere in the faceless, listless visage of Alex, somewhere in the dark of the eyes. Somewhere behind those things we can’t see through, ready to open the door for us and shed some light.

But I won’t give that horror away. You’ll have to stay with him until the end to see for yourself where the guilt seems to lie. From what he runs. Whether it be driven by passion, cursed by fate, blinded by love that best suits his story’s description and makes for a fitting headline—just say a prayer for this young, Invisible Man and enjoy the show. As you hurtle down the cobblestones, past the harbor wall, quickly gaining speed, perhaps you’ll remember: Never try to fulfill your best dreams. Only re-dream them.

— Evan Louison