BALLROOM DANCER

(Ballroom Dancer has its North American premiere in the World Documentary Competition at the 2012 Tribeca Film Festival—go here for TFF screening details/information—followed shortly after by an appearance at Hot Docs. Visit the film’s official Facebook page to learn more. Also read: A Conversation With Andreas Koefoed and Christian Bonke (BALLROOM DANCER).)

The premise is familiar from countless Hollywood movies: a veteran competitor with his best days behind him takes one more shot at glory. Ballroom Dancer is a documentary about Slavik Kryklivyy, a tortured, inspired, wildly talented perfectionist, an innovative former world champion of Latin dance, who’s determined to find his way back to the top with his new dance partner and lover, Anna Melnikova. Danish filmmakers Christian Bonke and Andreas Koefoed display a masterful talent for the medium, putting together a film with the narrative sweep and drama of a great, classic movie but going further, deeper and more specific by assembling it from the raw moments and real-life textures that can only be captured through documentary.

The first time we see the couple practice, Slavik fires eye daggers at Anna when she performs a spiral incorrectly; he tells her he’s gonna kill her, then kisses her hands and cheeks to make it better. At a lunch meeting, their new Scottish coach expresses confidence that they can be on top within a year or so, but with a slightly ominous qualifier: “…if you don’t make a mistake.”

At their first competition, Anna naively tries to convince Slavik not to worry: “If you start thinking something will go wrong, then it will go wrong.” Their performance, which to a layman’s eye seems nothing short of spectacular, gets them third place, and Anna is ecstatic, showered with praise by proud friends and family, holding a massive bouquet of flowers. Meanwhile, Slavik goes through the motions of a few hugs and high-fives, and mutters, “I’m sure we will learn to dance together.”

The winner is Slavik’s arch-rival of sorts, his former partner Joanna who’s like a character from a novel with her crown of wavy, golden-blond hair. She’s a recurring presence, but we never hear her speak; she effortlessly performs her dazzling moves on the dance floor and happily waves to the crowd, winning one competition after another with her new partner.

The winner is Slavik’s arch-rival of sorts, his former partner Joanna who’s like a character from a novel with her crown of wavy, golden-blond hair. She’s a recurring presence, but we never hear her speak; she effortlessly performs her dazzling moves on the dance floor and happily waves to the crowd, winning one competition after another with her new partner.

Anna has a daunting mountain to climb. Partnering with one of the great Latin dancers of a generation is the opportunity of a lifetime for her, and in theory her easygoing and optimistic temperament should be the perfect compliment to Slavik’s dark and moody genius. But Latin dance is a physical manifestation of giving and receiving passionate feeling, and what Anna gets from Slavik has a strong component of anger and mistrust.

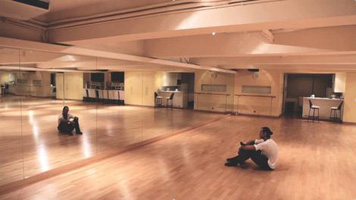

Slavik’s internal disconnection is brought to light when he quickly dismisses the topic of meditation, saying it makes him fall on the floor later; as an alternative, he mentions putting on some Elvis Presley in his room and jumping on his bed. At one point, over Anna’s protests, he skips lunch entirely, preening compulsively in front of the mirror.

After a disappointing fifth place at the UK Championships, serious trouble starts to brew; coaches and advisers end up doubling as couples therapists, trying to get Slavik to ease up on the demands he puts on Anna, while Slavik becomes increasingly frustrated with what he perceives as her lack of commitment. He starts to exhibit what becomes a recurring thousand-yard stare.

Bonke and Koefoed do a miraculous job of building a rich and detailed story from their footage—in fact, a group of concentric stories. There’s a war going on inside of Slavik, trying to balance his fear and desire for complete control with a need for effective communication and spontaneous creativity. This in turn gets expressed in his relationship with Anna and in the dance. But there’s another kind of dance going on as well, the one between the lover/partners and the camera—the raw humanity that Slavik in particular is willing to expose belies an understanding that his real life is also a performance.

This becomes most apparent in an astonishing final act in Hong Kong. A dance in which the couple’s entire personal and professional relationship is at stake is followed by a stunning monologue by Slavik and a highly theatrical aftermath. It’s operatic in its emotional impact; the film suggests that we’ve witnessed nothing less than the man and the artist finally merging into a single being.

— Paul Sbrizzi

Pingback: A Conversation with Andreas Koefoed and Christian Bonke (BALLROOM DANCER) – Hammer to Nail