(The 2017 SXSW Film Festival opened on March 10 and ran all week until March 18. HtN has you covered and GUARANTEE more coverage than any other site! Check out this review of I Am Another You, the winner of a Special Jury Recognition for Excellence in Documentary Storytelling at this year’s SXSW.)

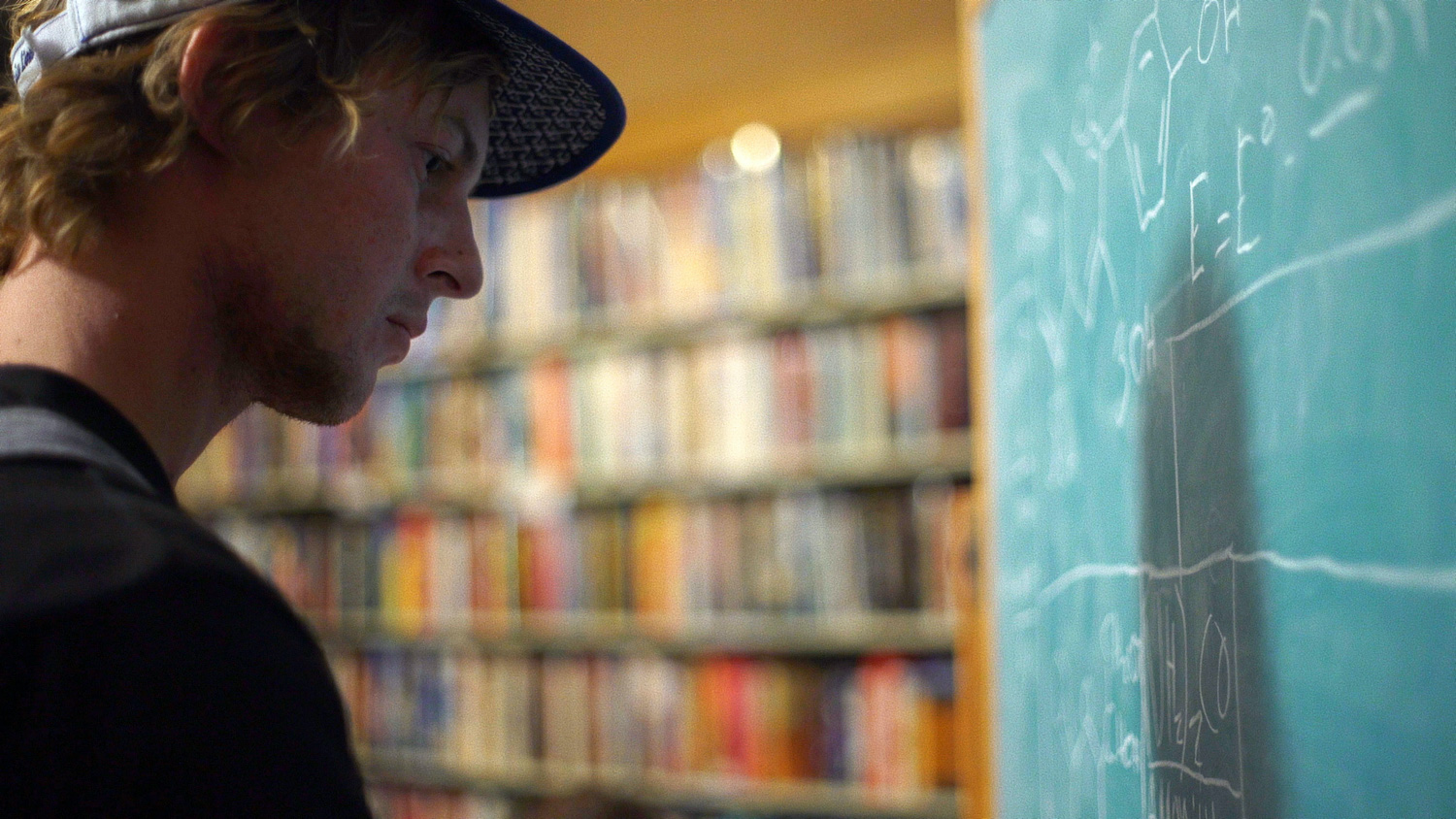

Winner of a Special Jury Recognition for Excellence in Documentary Storytelling at the 2017 SXSW Film Festival, I Am Another You, the second documentary feature from Nanfu Wang (Hooligan Sparrow) finds the director on the road with her primary subject, a young man named Dylan Olsen, who is homeless by apparent choice. She meets him on a cross-country trip she undertakes shortly after coming to the United States, from her native China, to study filmmaking. As she explains in the opening, she chronicled her journeys by filming all the conversations she had with strangers, so she presents a detailed record of these early research videos, including her initial encounter with Dylan. Handsome, fit, articulate, and blonde, he looks like a stereotypical surfer, though there is a distant, almost damaged, look in his eyes. Something in him attracts her attention, and soon she, too, is living as he does, sleeping outside, seeking food and money from strangers, and exploring what she sees – especially coming from her repressive and oppressive homeland – as the ultimate freedom to do what you want, how you want, when you want.

Divided into three chapters – “There Is No Time,” “The Freedom to Choose” and “I Am Another You” – the movie is a compelling hybrid of personal reflection and observational filmmaking. At first, we question why Dylan might make a good subject of study. As Wang, herself, acknowledges, he is not your typical homeless person, at least not yet. His youth, attractiveness, and, she freely admits, race, make those with whom he interacts more likely to help him. He is also blessed with a natural gregariousness that draws people in. As we get to know him in the first section, it seems unlikely he will ever starve. He is, indeed, a free spirit, eschewing society’s traditional norms for a life of his own making. But then we also discover his history of drug addiction, his current full-blown, active alcoholism, and we begin to understand, as does Wang, that there is more to Dylan’s story than pure surface rebellion.

We begin in 2013, but then flash forward two years, where Wang, after filming another movie on civil rights in China, picks up Dylan’s thread, this time in Utah, where she tracks down his family. Here we learn about Dylan’s past, through interviews with his father, a deeply reflective police detective who feels helpless when it comes to solving the puzzle that is his son. Fortunately, he has two other children, both more stable, and both more inclined to accept the Mormon faith in which they were raised. As the story increases in complexity, we marvel at Wang’s ability to elicit thoughtful confessions from those at whom she directs her camera. When, in the final chapter, she finally explores Dylan’s mental-health issues – and the title comes from a poem Dylan has written about the voices in his head – we realize that, little by little, Wang has shepherded us on a journey that grows ever more profound with each moment. If not every insight into Dylan’s condition is equally perceptive, the overall experience of watching both Dylan and the director fumble their way towards understanding is deeply moving, as well as cinematic.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)