A CONVERSATION WITH Mario Gaoa and Danielle MacLean (WE ARE STILL HERE)

We Are Still Here, an anthology film made by 10 directors, just premiered at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) (where I reviewed it). It tells the story of colonialism in the Pacific and its enduring aftermath, focusing mostly on the sins of the British Empire (beginning with Captain James Cook’s arrival in the region in 1768), mixing animation and live action as it goes. Just after leaving TIFF, I had the chance to speak with two of the directors, Mario Gaoa and Danielle MacLean, respectively from New Zealand and Australia, via Zoom. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: Please start by explaining which part of the film you created.

Danielle MacLean: I directed and wrote “Lured,” which was the animated piece, and worked with animators Huni Bolliger and Dan Hartney.

Mario Gaoa: I am one half of the directing duo that shot “The Uniform,” which takes place in Gallipoli during World War I.

HtN: How was the idea of this omnibus, or portmanteau, film pitched to you?

DM: So our screen agency, the Indigenous branch of Screen Australia, and then the New Zealand Film Commission, they both put out calls to Indigenous filmmakers around Australia and New Zealand asking, “Have you got an idea? Do you want to say something in response to Cook’s 250th anniversary?” And we just all applied and then they shortlisted us, and that’s how we pretty much came together.

MG: They just picked the best they could find, really, didn’t they? (laughs)

HtN: The crème de la crème.

MG: (laughs) The crème de la crème. You got it.

HtN: And you, Danielle, are from Australia, and you, Mario, are from New Zealand, right?

DM: So I’m from Central Australia, and I’m Warumungu and Luritja. I also have Scottish heritage.

MG: Both my co-director Miki Magasiva and I are Samoan. And you’ll see tropes of that and themes of that inside our film. We’re born in New Zealand, but of Samoan parents.

HtN: How many different Indigenous communities are represented in this film?

DM: There are eight films.

MG: Three of which are Maori.

HtN: But there’s overlap, because there’s more than one Australian, more than one Maori, right?

DM: Yeah. The animation, “Lured,” is obviously a response to colonization and so it’s set on the coast, but really my family and my connections are in the desert. But it’s using those tropes to talk about colonization. Because obviously Cook’s boat, the Endeavour, arrived in Australia and then it affected everyone around the country.

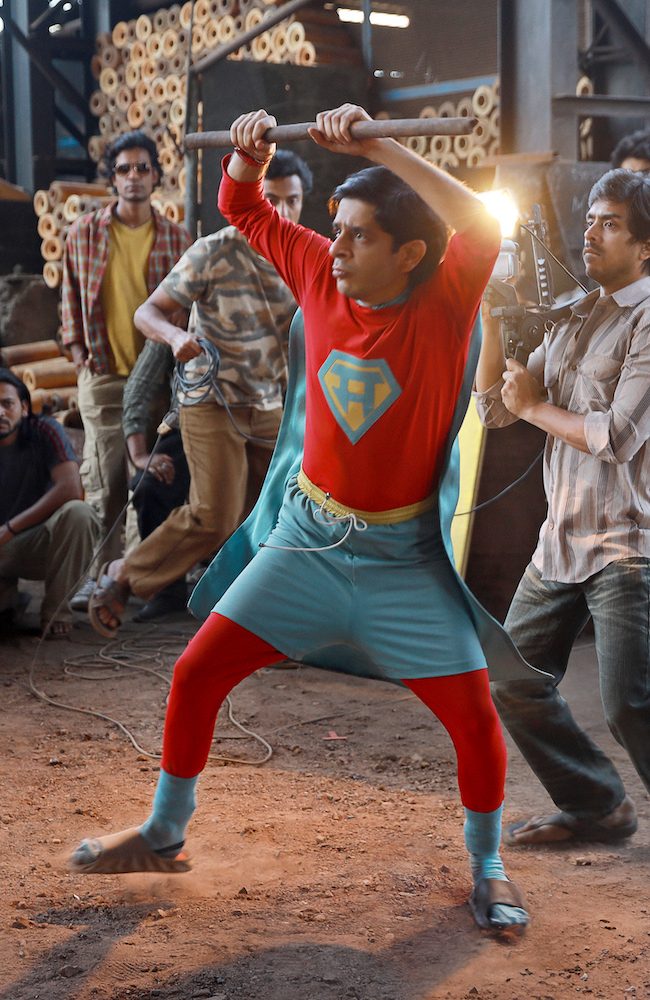

A still from WE ARE STILL HERE

MG: There are certainly Maori stories inside which are clearly identifiable. There’s our Samoan story inside there, set in Turkey.

DM: Of the Australian stories, one was filmed in Melbourne, two of the other ones were set in Alice Springs. Mine is all shot on green screen. So we shot that in Brisbane and then essentially created the east coast of Australia.

HtN: Obviously, you’re focusing on the 250th anniversary of Cook’s arrival in your own unique ways, but the stories really range. We’ve got that post-apocalyptic, dystopian future, for example. You were clearly given a lot of free rein, but what kinds of guidelines were you given, each of you, for your pieces?

DM: Because we were brought together as a team quite early on, once they shortlisted who was going to be in it, we got to actually collaborate. We already had our stories. I feel like my film probably changed quite a lot because we needed something to bind all the stories together, which became my piece. It felt like that would help connect all the stories. But I think we all came in with quite a strong idea about what we were making. In terms of guidelines, I think, no, it was really a group decision to actually intercut the movies. They were going to probably just sit as films, but we wanted to do something more interesting, or more challenging, anyway.

MG: Which was more challenging. And way more interesting. But you are right, because when we got together, we started off as individual movies laid side by side. And the scope of it was tethering the stories back to that 250th anniversary of Cook. But then that changed. I think the overarching theme of where we originally started changed when we decided to cut stuff up.

DM: Yes. It became about resistance and survival and actually connection back to country and family and community.

MG: I think we also spoke about whether we wanted to celebrate Cook and 250 years of his colonizing. And then I think the answer was no. So let’s take that away and focus more on stuff that we want to talk about, that we want to say in our films.

HtN: There was a supervising director beyond the eight different films. Is that the person who oversaw the intercutting and pulling everything together?

DM: Yes. So that’s Beck Cole. Because I guess the thing was, you can’t make this by committee. Someone has to decide what goes and what stays, and she was that person. What actually happened was we all got a chance after the shoot to sit with the editor and we did a kind of director’s assembly, that is pretty much just an assembly of the short film as we saw it, the best takes. And then Beck went with Roland Gallois, the editor and we looked at the rough cuts, gave some feedback, but then had to let go of things as directors of our own shorts and trust in the process that they were going to pick the best to make it fit together.

MG: And that was always going to be super tough.

DM: It was.

HtN: What was left on the cutting room floor for each of you that was the most painful thing to let go?

DM: We probably worked on our film longer than anyone else because it’s animated. So we did lose quite a few minutes actually. I think “Lured” is only seven minutes in the film. I think we probably lost maybe three minutes. And I understood those decisions because it was like, “Okay, there was the daughter in the city.” But you’re seeing that in the other films, what that represents to Aboriginal people, to Maori people, to Samoan people. So that was lost. And that it was difficult, everything we lost, but I also understood the process and the need for that process.

MG: We were the same as Danielle in the sense that there was some stuff that we felt was like, “Oh man, this shit was fucking awesome. We should have it inside there.” But at the same time, you just have to let go. And we always understood we’re not going to get everything that we want to see inside there. But if you’re asking me what’s the one thing that I really wanted to push inside there, it is a shot of when Bernard, my main character, is looking for stuff and he finds a cigarette to throw over to his Turkish mate. There’s a shot and it’s a little picture of a pig.

The photo of the pig just gives us a little bit of background around Bernard. A lot of the soldiers who went to Gallipoli, many of them didn’t actually make it in there. But they came from the islands and they spent some time training in New Zealand before they were shipped out. And Bernard takes a photo of his pet pig to the trench in Gallipoli.

HtN: One thing that could happen later is you could have a Blu-ray release where you have the film as it is and then the special features are all of these self-contained shorts as you originally cut them. We could watch them and see what you wanted, and then perhaps have an interesting understanding of the final product. I’m a film professor, so that would be great for my classes.

DM: That was actually what we had intended to do, but budgets never stretch.

HtN: I live in a country right now, the United States of America, where there are quite a lot of people who are unfortunately taking umbrage with this notion of examining the past in order to understand the present and the future. We have folks on the extreme right who think it’s somehow horrible to talk about slavery and the Jim Crow American South. Your synopsis in the press notes begins in this way: “In order to move forward, we must first look back.” So how would you explain the validity of that notion to somebody who just doesn’t get it?

DM: I think with truth telling, you need to understand the past in order to actually recover from it. We talk about reconciliation in Australia all the time and you have to acknowledge the things that have happened. In Australia, there’s a lot of questioning of the way Indigenous Australians see what happened in our past, the things that we see as our history. And that’s really difficult if people just want you to move on, before they’ve actually acknowledged that it’s happened.

MG: Totally. Yeah.

DM: So I think what we’re trying to say is we’ve got to acknowledge and grow as people in order to move forward as a country.

MG: As a people, as a community, as a race, you’ve been able to look and examine your faults. If you want to become better, you have to realize that if there’s something wrong, something needs to change. And a lot of times you can only do that if those situations are presented before you to examne. So looking back does certainly, for most of us, inform us of which direction to take to become better people, become a better community, to become a better human.

Filmmaker Mario Gaoa

HtN: Beyond having to cut things that were dear to you, like the pig, what actual production challenges, if any, did you face in the making of this? You’re doing animation, Danielle, which has a different set of challenges than what Mario faced. But Mario, you were shooting in a simulacrum of trench warfare. I’m sure that wasn’t easy to set up. So what challenges did each of you face in the making of your individual pieces?

DM: Well, the challenge everyone’s had in the last three years was COVID. So that slowed us right down obviously, though that’s quite boring to talk about at this point. Mario, do you want to answer first?

MG: Sure. For us, we actually had a pretty good run. We had a couple of rain days that got a little bit sketchy because parts of our trench weren’t officially OSH [Occupational Safety and Health] approved. Is the producer here? (laughs) So there was the usual sort of day-to-day challenges. But I think the biggest one for us was we decided to challenge ourselves and really do stuff that we wouldn’t normally do. And it was very time-expensive. So I think just for us, it was the time. We wanted more time. I think we had three days or four days, maybe. Maybe three.

DM: Three.

MG: Three days.

DM: And we were going to have four and then it got cut down to three days because one of the other films needed longer because of the travel involved where she’d set her film in Central Australia. So that was pretty challenging because that was only a week out. So then it was adjusting to that. The reality is we all had around three, three and a half days to do it.

HtN: Well, Mario and Danielle, I want to thank you very much for chatting with me.

MG/DM: Thanks!

Filmmaker Danielle MacLean

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)