A Conversation with Lina Vdovîi & Radu Ciorniciuc (TATA)

The new documentary Tata marks Moldovan-born journalist Lina Vdovîi’s feature-directorial debut. She is not alone in the process, working closely with her Romanian husband, Radu Ciorniciuc, with whom she co-wrote his own directorial debut, Acasă, My Home. Together, they explore how past trauma informs the present. After years with almost no contact with the man who made her early years unbearable, Vdovîi now faces a dilemma: to help her father or not. He long ago left Moldova to work in Italy, but at the moment is himself suffering abuse at the hands of his employer. While Vdovîi strives to get him some relief, she revisits the myriad ways in which toxic masculinity informs her family’s history as well as her country’s traditions.

Tata had its world premiere at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival—aka TIFF—where I reviewed it. I had the opportunity to sit down with both Vdovîi and Ciorniciuc while there. Here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity. Their English is very good, although where I have had to slightly change wording to better fit American idioms, I have done so.

Hammer to Nail: Could you please explain what linguistic and ethnic differences, if any, exist between Moldova and Romania?

Lina Vdovîi: So, Moldova is located right between Ukraine and Romania. It used to be part of Romania until 1812 when Russians first invaded. And then we were under their occupation until 1991. Moldova is a former Soviet republic with a hardcore communist background. We speak the Romanian language but with what’s called the Moldovan dialect, with a different accent and some words that are older that Romanians don’t use anymore. Any Romanian who goes to Moldova, and vice versa, can be understood. It’s the same language.

HtN: That makes sense. A forced separation like that would lead, over time, to some minor differences.

Radu Ciorniciuc: Only linguistically. Internally, we feel we are the same, as Moldovans and Romanians. We consider ourselves as part of the same country, more or less.

HtN: (to Lina) You live in Romania now, though, right?

LV: Yes. I left to attend college in Romania when I was 18. I studied journalism in eastern Romania and then moved to Bucharest, the capital, and I’ve been living there ever since. So, 18 years already!

HtN: And you, Radu, are originally Romanian?

RC: Yes. From the eastern part of the country. I’ve been living in Bucharest for all my adult life.

HtN: Was Acasă, My Home your first collaboration?

RC: We used to collaborate on other stuff before Acasă. We started out wanting to make a feature-length reportage for the international media.

LV: It wasn’t supposed to be a film in the beginning, but then we realized there was more to it, that the story was much more complex, and then we ended up following the family [in Acasă] for four years. And then we finished the film and it came out.

RC: Which is pretty similar to what we started doing with Tata: we started with one thing in mind and then it developed into something much more complex and profound. It took us way more time than we anticipated in the beginning.

HtN: So when did you first meet, then?

LV: We’ve known each other since 2012, first as journalists, working in the same community and sometimes working on the same projects together, and then with Acasă, we became colleagues in filmmaking and then a couple a few years later.

HtN: In what year did your father, Lina, first reach out to you for help, and at what point after that did you decide to start filming the story as a documentary?

LV: It all started in August of 2018, so 6 years ago, when I received this video message from him showing bruises on his arms, and we actually started filming right away, because we were already working on Acasă and knew that filmmaking was this new direction that we were trying, and so we jumped in the car with our cameras. We had a sense of what was going on, since we in the family knew that he was always fighting with his employer, but we didn’t have all the details. I was the first person in whom he confided and to whom he told the full story.

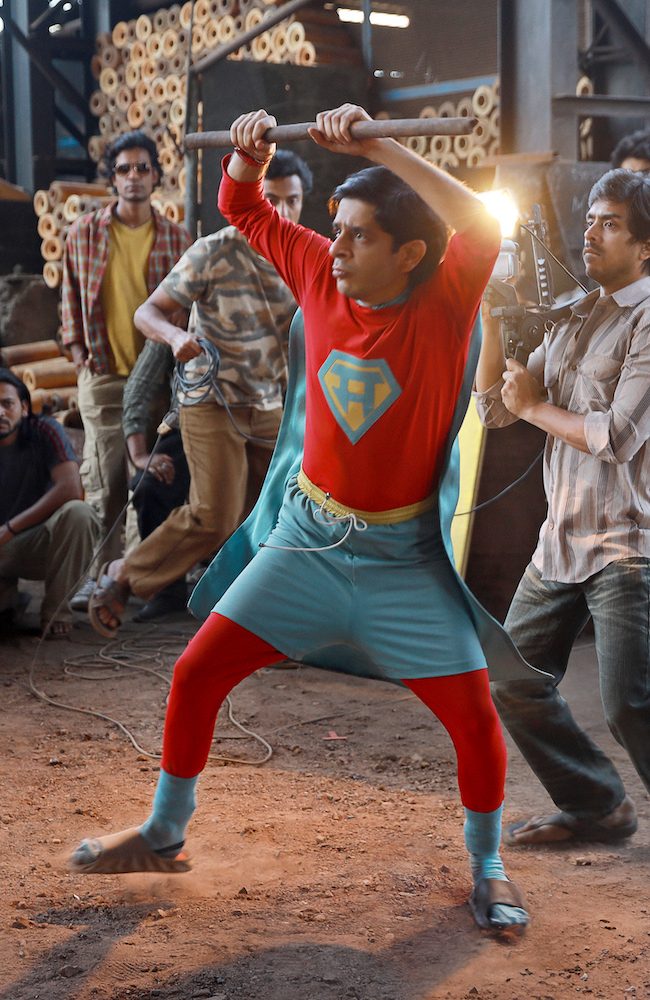

Our Chris Reed, Lina Vdovîi & Radu Ciorniciuc

So we went there straight away, with professional cameras and hidden cameras, knowing that there was something that needed to be investigated that could potentially turn into a film, but we didn’t know what kind of film. In the beginning, we talked about making a film about an immigrant worker, who happens to be my father. The main topic was going to be exploitation of immigrant workers, but then it turned into something more personal and intimate, and as we go deeper into the history of my own family, the film takes a different approach.

RC: We were used to covering stories on modern-day slavery. In our twenties, we traveled quite a lot in Europe, to farms and factories and so on. We knew a lot about this topic. So when we went to investigate what was happening with Lina’s father, we had an aim and a structure for the film. But we then realized after meeting with her father that this kind of investigation would take more work than we anticipated. I’m grateful I could be there to support her and the project.

When Lina started writing about it and we were talking about the topic of violence—because that’s essentially what we were investigating—Lina made the decision to go deeper into this violence theme as one of the reasons that her father accepted to live under those horrible conditions. Her theory was that the aggression and abuse that he was subjected to by his boss was somehow a language that he understood. It was known to him. That was the moment where Lina decided to take a look at her family history, since the violence has much deeper roots.

HtN: If violence is the language that you, yourself, are used to using, then you are perhaps more accepting of it being directed at you. That’s interesting. So, beyond the emotional challenges that we see throughout the film for you, Lina, what kinds of additional logistical challenges—other than outfitting your father with a hidden camera—did you encounter in the making of the movie?

LV: I’m not sure if this is logistical, but it was pretty hard in the beginning to find a good lawyer who would take my father’s case. We tried working with other people, as well, before we found the lawyer you see in the film, but it didn’t feel like they actually understood what my father was going through, even though we had compelling evidence. Apart from the video, my father had gathered other evidence, like his working hours, letters from the employer, photos and all that stuff. Some of the lawyers we initially found were not really devoted to the case. I had to make some calls to the filmmaking community that we knew, and in the end we managed to get this association of attorneys that specialize in helping migrant workers in Italy. In five minutes, they knew exactly how to tackle this. It was very clear from that point on. But it took us about a year and a half, or something like that.

RC: Something that didn’t help was the judicial system, itself. It takes a lot of time for someone in Lina’s father’s position—for a worker—to sue his employer. It takes a long time for it to work its way through this complicated system. It’s the major problem of being an immigrant worker in Europe.

LV: And also, another thing that I just remembered was the cameras that my father broke. (laughs) I don’t know how many cameras he broke.

RC: Just the hidden ones!

LV: Yes, the hidden ones. We had to constantly send him new cameras and explain to him how to use them.

RC: Working with them is quite physical. There are the wires …

LV: He had to always be careful not to let any of the wires be seen by his employer. So that was definitely something of a challenge, all those cameras that we sent him. And also, he’s an old man. He’s 67 now. It was hard for him to learn to use all that technology. Not only did he have to learn how to use the cameras, but there was also the laptop to which he had to copy that material and then make sure it was on the hard drive that he would then send to us.

A still from TATA

RC: And then we had to constantly train him to make sure that the footage he was gathering was gathered in a journalistically ethical way, so that he doesn’t provoke, he doesn’t alter the reality … all those things that we learned in journalism school. We had to make sure that he didn’t expose himself nor expose the process, itself, so that we can have a strong case against the abuser.

HtN: As you mentioned, the film tackles many issues other than those of being an immigrant worker, including the history of violence in your family, Lina, and that of the larger culture in which you grew up. Your mother talks a lot about how she changed while your father was abroad. But when he comes back, it looks like some of the old patterns of behavior reassert themselves. What are they both like, separately and together, now? Is he still back in Moldova?

LV: No, he’s back in Italy, working for a different employer, because he’s trying to get as much into his pension as he can before he finally retires. His plan is to eventually go back to Moldova. I would say that every time he comes home, it’s the same, unfortunately. We don’t know what’s going to happen once he finally returns for good. For now, we still have these short visits. You know, they’ve now lived separately for 25 years. Every couple has its own language of communication between them, and they probably lost it decades ago. We don’t know what’s going to happen, afterwards. Maybe that’s a different story in a different film. (laughs)

HtN: That could be the sequel. But as someone who sees you discuss in the film the past history of violence, I feel this real anxiety for your mother when your father returns home at one point and appears to be just as controlling as ever. So I hope she’s OK!

LV: We are there and we are going to make sure that she is OK. She’s not going to go through anything alone. For now, she’s good, and she’s actually with our daughter, as we speak, and my father is in Italy. So as long as they are separated, it’s fine. But yes, it’s on our minds all the time, to make sure that she’s safe.

HtN: That moment in the movie where you and your father have something approaching a moment of reconciliation and apology is quite moving. He appears to take it to heart, although we can see some of the old behavior resurface. How much do you think he internalized the things in that conversation?

LV: A lot. I truly believe that he understood and, for the first time, got this perspective from somebody who’s not him, from a person whom he hurt. And I see by the way he speaks today that he’s learned many new things. But I also know that it’s really hard for someone to change unless they go through something that shakes them really strongly. And my father comes from a system and a society with a long history of abusive behavior, not only at the level of the family, but from the top of the society.

The Soviet Union was a country—or an empire, as they called themselves—that dealt with a lot of general violence and aggression. That was one of its traits. All the men who grew up and were educated in that system are the same. All the men my father’s age are the same. So I know that what we did together in the film and the investigation broadened his understanding of violence in general and how toxic he was and how this aggression is not a good thing, but I also that it’s hard for someone who is 67 to entirely change his behavior, mentality, values, ideas. He’s always believed that a man must dominate and be powerful and arrogant and misogynistic and all those toxic traits that men from that part of the world have. And not only from there, I would say …

HtN: Indeed, I don’t think it’s only men from your part of the world who behave this way. If we look at the types of values that are being promoted by a certain faction in the United States, there’s toxic masculinity everywhere.

RC: The major difference is that this toxicity is not confronted in our part of the world. We know that it’s everywhere, but it’s not manifested in the same way. One of the greatest achievements—apart from making the film, itself—of what we did is that the movie speaks out against something that is so internalized and normalized. It’s almost invisible there, because it’s not confronted enough.

HtN: Well, thank you both so much for talking to me. I really enjoyed the film and I enjoyed the conversation.

RC: Thank you!

LV: Thank you so much!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)