A Conversation with Steve James (A COMPASSIONATE SPY)

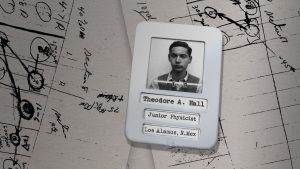

Steve James, Born in Hampton Virginia, graduate of the James Madison University, is one of the greatest documentary filmmakers of all time. His 1994 film Hoop Dreams is considered not just one of the greatest documentaries of all time, but one of the greatest films of all time. He has directed countless eye opening documentaries, another classic being The Interrupters. Steve is not just a respected member of the film community, he is looked up to by countless social studies professionals, his works studied by dozens of top tier universities. His latest film, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival, and releases in perfect timing with Oppenheimer, is the story of Ted Hall, a 19 year old man who made a very important decision while working on the Manhattan project. I spoke with Steve about his latest, which is called A Compassionate Spy, in the following conversation edited for length and clarity.

Hammer To Nail: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Bombshell: The Secret Story of America’s Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy, has been published since 1997, that is 3 years after Hoop Dreams. So if this information has been available for so long, why did you feel now was the time to tell Ted Hall’s story?

Steve James: Well, I didn’t know Ted’s story until right before I started making this film. And it was one of the producers on the film, Dave Lindorff, who’s an investigative journalist, who brought the idea to us. He had befriended Joan when he wrote an article about Ted. And Dave was someone we interviewed for Abacus and got to know. So he’s the one that brought it to my attention, and the more I learned about it, the more intrigued I became. That led to a three or four day trip to Cambridge, England to spend time with Joan and talk to her. That sealed the deal. I fell in love with the idea of telling Joan’s story as much as Ted’s.

I just thought she was an amazing person and told the story of an amazing marriage and amazing time. Then finding out that there was actual footage, And as it turned out, quite a substantial amount of footage of Ted talking about this before he died in the nineties. I was like, okay, I think this is an important story. Putin hadn’t invaded Ukraine. Christopher Nolan hadn’t decided to do Oppenheimer yet. I didn’t do this because I thought the world could find itself grappling with nuclear bombs any time soon. I did it because I just thought it was an extraordinary story, whether you ultimately agree with him or not about what he did. He acted with tremendous conviction and courage. And he was so young. He was so young! I did not know if anyone was interested in this story. I was. So I made it.

HTN: It is a very crazy story. How long ago was the article brought to you?

SJ: I think Dave’s article appeared in this, lefty periodical called Counterpunch, back in 2018. We started filming in 2018. Things got interrupted with the COVID. We continued on and then finished. We went back to Cambridge to spend more time with Joan in 2021.

HTN: Got it, so If I am not mistaken, this is the first time you are using actors to recreate moments in history. Why did you think that was right for this story and what was it like working with actors?

SJ: After spending that time initially with Joan and hearing some of the stories that were so particular and dramatic I thought, “how could we possibly visually represent any of this?” there’s no archival record to show any of this. There’s no way to fake it with archival footage, which a lot of times historical movies will do. She’s a great storyteller, but if we want to see anything, what is it going to be? So I felt pretty early on that, that recreation was really a way to go and partly for what I just said, but also partly because they were so young when all this happened that I felt like I wanted to really give viewers a window into their youthful sort of exuberance and passion. Because I thought it’s also a way for this story to hopefully speak to younger people today. you’re sitting there looking at a 91 year old woman talking about something that happened in ancient history.

Joan Hall in A COMPASSIONATE SPY

For a lot of people that won’t be entertaining enough. I wanted to really take you back to that time. I thought it was important. And I knew there would be people who would watch and go, “Oh, I don’t like reenactments,” or whatever. It was fun to do them and we decided to just go for it instead of doing the sort of standard, obscure their faces and just shoot interesting angles and never really see much. We just decided to go for it. But the actors I thought were excellent. They looked so much like young Ted and Joan that I was like, “you know what? Let’s just go for it. And if we’re going to do it, we’re going to do it.” Then Christopher Nolan came along and imitated what I did and took a lot of credit for it. What am I going to do haha.

HTN: They came out great. Besides the fact that he shared these nuclear secrets at such a young age, what was it about Ted Hall, his eccentricities, his nonchalant attitude that interested you so much?

SJ: There were a lot of things. Here’s a guy that graduated high school when he was 15 and he goes to Harvard. Harvard! He’s majoring in physics, And at the age of 16 and 17, he’s writing letters home to his brother, Ed, where he’s delivering an incredibly insightful critique of the educational system at Harvard. He’s all of 16 or 17. Someone so young, And yet he is so brilliant. He’s sitting here going, “here’s what’s wrong with Harvard.” Which is just kind of extraordinary. Then his steely spine, when the FBI came calling. He knew if they really had the goods on him in a way that they could arrest him, he’d be arrested and they hadn’t arrested him. And so his willingness to sit there and then stop cooperating and walk out was, I thought, extraordinary.

You know, Klaus Fuchs, who we’ve mentioned in the film and who also passed secrets of similar nature, we don’t put this in the film, but British intelligence called him and did the same treatment to him. He broke fast and ended up serving 14 years in prison for it. Ted never broke, which is kind of extraordinary. The other part of the story, that I had no idea about going in, was the whole thing with his brother. being this brilliant engineer in the Air Force who was designing rockets that eventually would carry nuclear warheads. When and if someone does the Hollywood version of this story, people would say,” oh, come on, you’re making up stuff, this can’t possibly be true.”. And it is true.

HTN: Which is why I actually think the reenactments worked so well for this, because it feels like a spy espionage, Hollywood movie. Speaking of the reenactments at around the hour, ten minute mark, we have this very powerful moment with the Rosenberg execution and Ted and Joan driving to the party. talk about your reaction to hearing that moment and how you wanted to execute that in the film.

SJ: I was just blown away by that story. There’s three interviews with Ted that we were able to access and the mother lode one. They’re all great really. One is very short. He sits on a couch. one including Joan, which is great because they recorded that one for posterity. they didn’t have any intention of sharing that with anybody. And the other one, which is a kind of the motherlode, was done by CNN, BBC for this series where they interviewed him for almost 3 hours and they used all of about a minute and a half of him in the series. But Joan had somehow struck a deal with the producer that they were going to get a copy of the whole interview for them. It took some doing to get that unearthed from CNN, but it was amazing to discover Ted talking about that very night where they went into the party and the Rosenbergs were being executed.

Ted and Joan Hall in A COMPASSIONATE SPY

It was like everything Joan had said was confirmed by Ted and supported by Ted.I was really excited about having them both tell us what happened and then finding a way to visualize that because it seemed like such an extraordinary moment. I’m really happy with how that turned out. They were devastated by it. the fact that you learned that Ted wanted to turn himself in with the hopes of saving the Rosenbergs. And Joan says in the film she convinced him not to do it because she said, “you won’t save them, you’ll just destroy us.” She was dead right on that. I mean, they would have both been executed in all likelihood, because even though she didn’t have anything to do with the spying, she enabled him just like Ethel Rosenberg knew about Julius’ spying and really had nothing to do with it. They executed her anyway.

HTN: It’s a very powerful moment, definitely one of the most memorable from the film. Simple question, but I’m wondering if Ted Hall were here today, what would you ask him?

SJ: He ultimately came to question whether he should have done what he did when it really became clear that Stalinist Russia was a terrible totalitarian state. He talks in the film about how he wondered at times whether he should have done it and that he ultimately landed on the fact that he really wasn’t doing it for the Soviet government, he was doing it for the Soviet people. He answers the question in the film, but I would have dove more deeply into that. Nobody asked him about his feelings about the subsequent huge arms race that happened between the Soviet Union and the United States. Did he feel responsible in some way? Now, the thing that has to be remembered, and I think it’s easy to watch the film and not quite get this, but it’s not like the Soviet Union wasn’t going to get the bomb. The Soviet Union was working on it. They had very smart scientists. Ted’s actions and Klaus Fuchs actions and maybe Julius Rosenberg’s actions led to them getting it more quickly but, it wasn’t about them not getting it. So we would have had an arms race regardless. I think that might have been what Ted would talk about. He didn’t cause the arms race. It just maybe started a little earlier. If the US had followed through on their war plans with a possible preemptive strike on the Soviet Union post World War Two, then I guess the Soviet Union wouldn’t have gotten the bomb. But at what cost?

HTN: Besides your obvious fascination with Ted Hall, another thing I noticed was how this tells Cold War history in a way that points to a new mainstream and more accurate perspective that amounts to more than just “Russia Is Bad.” Was that partly an objective here?

SJ: It became one as I got into it. I was aware of some of that history and aware of the great debate around the dropping of the bomb and Hiroshima and Nagasaki that has gone on to this day. I was aware of that. What I was not aware of was the degree to which the United States government, including Roosevelt himself, went to paint the Soviet Union as a treasured ally during the war to get the American people to really be supportive of the Soviet Union as our ally. And Roosevelt wasn’t stupid, but he realized that there was no winning this war without the Soviet Union, really. And that’s something most Americans have no clue about. They think we entered the war and we won it. We did D-Day. We dropped the bomb on Japan. All done. completely unaware of the degree to which the Soviet Union on the eastern front prevented Hitler and the profound loss of over 20 million people. So all of that just felt like it was important to become part of the story, because it’s all part of what informed Ted’s thinking and Ted’s choices that he made. And I knew it was history that most Americans, at the very least, are fairly clueless to.

HTN: So Joan Hall may just be the biggest ride or die ever staying with her husband after he reveals those nuclear secrets. I’m just wondering, what was it like spending time with her and how palpable was that love like even today?

SJ: Well, it was a big part of why I wanted to tell the story, to be honest. For a long time, the name of this film was going to be Ted and Joan. I still like that title, but I kind of got talked out of it because people said, “Well, they might be thinking, the films about Ted Kennedy and Joan Kennedy.”I was like, “That’s not going to be an issue. But okay.” I like the title we ended up with, but that tells you something. I was as much taken with Joan’s story and with their story together as I was with Ted’s story, which is saying something because he had an extraordinary story. I just felt like so much of this history, when it gets told, gets told in sort of the broad sweep of the politics and this had the potential to do that, tell that story, but in a way that was a love story. That was greatly appealing to me.

HTN: I think the tone of the film is definitely one of the most important aspects. It remains menacing yet sweet the entire time. How did this tone come to life in the editing room, and was that something that you were thinking about as you made the movie?

SJ: Well, I’m going to say yes, because that sounded like a compliment. It was important to never lose sight of the personal. It’s one of the reasons why I wanted Sarah and Ruth, their daughters to be a part of the film, too. I didn’t just want to talk to Ted. I wanted to see them all together. I wanted to know the extent to which this shaped or didn’t shape their lives growing up and when they found out what it meant to them. It’s also why I sought out Savi’s kids, Sarah and Boreal. I also wanted to try to understand what it means to grow up with parents who have done something like this. I think that, because I was smitten with their love story, I wanted to never lose sight of that. The human aspect of it, but at the same time do justice to the broader spy story and the sort of broader political and sociological story.

HTN: Yeah, well, it worked out. I just have a couple more questions here. I’m sorry I have to do this, but have you seen Oppenheimer and what are your thoughts? Also, was A Compassionate Spy release at all in relation to Oppenheimer‘s or was that just a coincidence?

SJ: Last question first. Not a coincidence. Magnolia, this is not their first time putting a movie out. They said, “hey, we want to put this out after Oppenheimer is out there, but not too far after, because there’ll probably be a lot of interest.” They were nice enough. They didn’t want to put it out before Oppenheimer because we didn’t want to steal any box office away from Oppenheimer. I mean, you know that would have been a really unfortunate thing for us to completely steal all of Christopher Nolan’s audience away (wink wink). I like the guy. I love his work. We hope that all these people who see Oppenheimer will be so curious to know more that our film will be there to tell them more, So that was definitely purposeful.

I really liked Oppenheimer. I mean, I like Christopher Nolan’s work. I liked how much it digs into the weeds of it all. I was surprised that there were certain things they did not get into that we got into. But I’m happy they did not because it gives our film a chance to address certain things that they don’t address, even though it’s a huge three hour movie that gets into a lot. And I love the fact that it became so clear watching Oppenheimer that Ted and Oppenheimer shared a kind of similar political sensibility. They were both leftists and they both wanted to be a part of this for science, but also to beat Nazi Germany, they were both Jewish. The very thing that derailed Oppenheimer in the postwar world and that they tried to take him down on is the very thing that actually Ted Hall did and that Oppenheimer didn’t do. Ted, in many respects, even at the age of 19, I think on some level, felt more palpably the dangers of where this could all lead. I think Oppenheimer was more swept up in the creation, and understandably so. He was heading up this extraordinary effort. I mean, can you imagine? So I think Ted had room and the opportunity to really look at what they were doing and ruminate on, “what exactly are we doing here?” And it provoked him to act. I think with Oppenheimer, a lot of those misgivings came later, then in the midst of it. That’s one of the things that comes through in the film, which is part of the tragedy of his story.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)