A Conversation with Samuel D. Pollard (ACORN AND THE FIRESTORM & SAMMY DAVIS JR.: I’VE GOTTA BE ME

(Readers, please note: you can hear a portion of this interview on Chris Reed’s excellent podcast on documentwry filmmaking, The Fog of Truth.)

(Readers, please note: you can hear a portion of this interview on Chris Reed’s excellent podcast on documentwry filmmaking, The Fog of Truth.)

I met with director (and NYU professor) Samuel D. Pollard on Saturday, March 24, at the 2018 Annapolis Film Festival, where he screened not one, but two films: Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me (which I saw and reviewed in Annapolis) and ACORN and the Firestorm (co-directed with Reuben Atlas, and which I saw and reviewed at AFI DOCS 2017), both documentaries of enormous cinematic merit. The former is a mesmerizing portrait of its eponymous subject, one of the 20th century’s great performers, as well as a champion of civil rights. The latter profiles the rise and fall of ACORN, the now defunct non-profit community organization devoted to helping the poor and disenfranchised, which became a target of right-wing activists after proving extremely successful at voter-registration efforts. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, Sam, let’s start with ACORN and the Firestorm. How did you team up with Reuben to co-direct that film? What came first, the subject or the team?

Sam Pollard: The team came first. Reuben and I had met a few years before. I was the producer on the first film he made, entitled Brothers Hypnotic, and his mentor, and I helped him get that film off the ground.

HtN: Was he an NYU film student?

SP: No, he was a young man who had gone to law school and become a lawyer. His mother was a documentary filmmaker, but his father was a lawyer. An activist lawyer.

HtN: In fact, his father is in the film, right?

SP: Yes, his father, John Atlas, is in the film. And after we finished Brothers Hypnotic and it got released, he came to me and said his father had written a book about this organization called ACORN. He gave me a copy and he said, “I think it should be a film.” His father had a rolodex with all the numbers of the many members, and so I said, “Yeah, sounds like it would be a really good film.” And after I read the book, I was even more engaged in the idea of doing a film.

So, we started this five-and-a-half-year journey to get the film off the ground. We interviewed the original founder of ACORN, a gentleman named Wade Rathke, who was in New Orleans, so the first shoot we did was in New Orleans in, let me say, 2012. Something like that. And then we started to raise money … slowly raise money: $50,000 here, $75,000 there, $25,000 here. And then, ITVS, based in San Francisco, to whom we had applied 2 or 3 times and been rejected, finally decided this last time to say yes, and gave us the largest amount of money, which was about $370,000, which enabled us to shoot more and start editing, and we were finally able to finish the film in 2016.

HtN: Well, I really enjoyed the film. I, however, have never co-directed a movie. What are the challenges and/or benefits of co-directing a film vs. doing it solo?

SP: You know, the biggest challenge in co-directing, and I’ve done a lot of it now, is…(laughs)…being able to submerge your ego and not feel like, “It’s gotta be mine, completely.” And that’s hard. I’ll be honest with you. Even at this stage of my life, it’s hard. And so, you always have to walk this sort of delicate line where you have to express yourself, but you also have to be open to your co-director’s point of view. And sometimes, you disagree, and then you have to work out…(laughs)…that disagreement. Sometimes you can work it out in a very gentle way, sometimes…(laughs)…you have to work it out in a more aggressive and hostile way, but try not to take the hostility to such a point where you want to kill each other. You may want to almost kill each other, but you don’t. (laughs)

HtN: Right!

SP: And sometimes, when you co-direct, depending on the project, you have to be able to say, “Well, this person should maybe be the lead director,” because he may have more invested in the project, emotionally, than you do. So, there were times in the film, when we would look at cuts where there would be certain sequences where I could see that Reuben was more invested than I was, so I would pull back a little. And there were times where I was invested in a certain point of view that I didn’t feel was coming across, and I pushed. So, it’s a delicate dance. (laughs)

HtN: That’s fascinating.

SP: Yeah. ‘Cos I’ll be honest with you, the first time I did it was back in 1987/88, with Eyes on the Prize, Season 2, for Henry Hampton, and he created what we called these “salt and pepper” teams: there would be one white producer and one black producer. (laughs) And I think he did that because he knew that would … (laughs) … bring some tension. And it sure did. And it was my first time directing a big project, and my first time co-directing and co-producing with someone and, quite honestly, I didn’t handle it was well as I handled it now. (laughs)

A shot from “ACORN and the Firestorm”

HtN: But out of tension can come great creativity, too.

SP: And we were able to create a couple of good shows. (laughs)

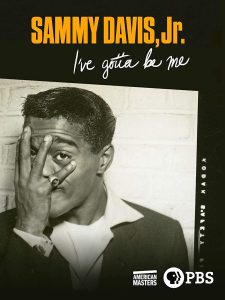

HtN: Great! So, let’s move on to Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me. You made the documentary for the PBS American Masters series. Was that commissioned? Did you come up with the idea and then pitch it to them? How did that work?

SP: It was commissioned. The executive producer, Michael Kantor, had wanted to make this film about Sammy Davis, Jr. about 5 or 6 years ago. He engaged a gentleman named Laurence Maslon, who’s a colleague of mine at NYU, teaching in the performing-arts, or acting, part of the school. He did a lot of research, they brought in a lot of scholars and historians and biographers who had written about Sammy, and Larry wrote a script, a real, full script. And they submitted to the National Endowment of the Humanities, and they got a grant. I think they got about $700,000.

HtN: Wow!

SP: Then, they knew they needed more money, so they went out and raised an additional $500- to $600,000. And originally…I wasn’t the original director. There was another person attached to direct, and he was brought on and started doing some interviews. This person, I happen to know personally, and he initially wanted me to just edit for him, and I said I would do it. But a third of the way through the process, he had some personal issues, and he had to drop out. And I was working on another project, but then Michael Kantor called me and said, “This director can’t do it anymore, would you be willing to take over as director?” Now, out of respect for that original director, I felt like I needed to talk to him first, to see if he would be cool with it, because I didn’t want to just say, “Yes, I’ll do it!” And I worked it out with him, and I took over as director.

HtN: So, I’m curious, are there any format requirements, or restrictions, that PBS imposes that affect the way you might otherwise work? Is it just up to you to create the film?

SP: Yeah, it’s up to me. The only caveat that they have is that you have to make it either a 2-hour film or a 90-minute film, because that’s their time frame. It’s not like HBO, where you can make a film that is 2 hours and 6 minutes, or you can make a film that is 97 minutes.

HtN: But your film is less than 2 hours and longer than 90 minutes … does it fit into the 2-hour program?

SP: (laughs) No…(laughs)…my film is almost 100 minutes.

HtN: Right!

SP: So, initially, I had a cut that was almost 2 hours, which fit the PBS standard. But I felt it was too long. So I chopped it down, got it to 100. Then Michael said, “Well, if you want it to be within the PBS, it’s gotta be a 90-minute film.” So then we chopped it down, but didn’t like the shortened version, so we went back to the 100 minutes. So … (laughs)…the compromise we came up with is that when it goes on television, I added a sort of 10-minute epilogue…

HtN: Ahhh…

SP: …(laughs)…to fill out to 2 hours.

HtN: Well, that’s great! That’s funny.

SP: That’s what I did!

HtN: So, were there any access issues? Was there anyone who didn’t want to be part of it? I noticed that [Sammy’s ex-wife] May Britt is not in the film. Also, we only hear Harry Belafonte’s voice, rather than see him talk. Were there reasons for that?

Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me

SP: Yes, there were. Reason 1, for May Britt. We reached out to Sammy’s and May’s daughter, Tracy Davis, to do an interview, and I said I’d love to interview her about her dad, and also asked if she could persuade her mother, May, to come do an interview. And she said she would. So, we tried to set up an interview in Los Angeles, but it didn’t work out. So then we said, “OK, we won’t be able to get your mother, but could we still do you” And she lived in Nashville. And again, she said yes, and she helped us find a location in Nashville. So, I hired a crew in Memphis, to drive to Nashville, and I flew into Nashville one day, and we had the crew, makeup and everything for her. We set up, the call time was 12:30: 12:30, no Tracy; 12:45, no Tracy; 1:00, no Tracy. So I text, I phone: no response. I send a PA to her house: no response. To this day, I have never heard from her. She never showed up. She cost me probably $2000 that day, in crew.

HtN: Did you see Agnès Varda’s Faces Places last year?

SP: Sure.

HtN: It’s like Jean-Luc Godard, at the end of that.

SP: Never showed up. Leaves a note.

HtN: (laughs) Exactly!

SP: And then, for Harry, well, I know him, personally. And so I reached out to Harry, through his intermediaries. Reached out two or three times, and he finally said no. Harry said no! And I was like, “What?” He knew Sammy really well! He was his best man at his first marriage. They even tried to start a production company together. But he said he didn’t want to talk about Sammy. So…I had edited, for Alex Gibney, two years before, a four-hour documentary about Frank Sinatra, and when we were in the process of editing that film, Gibney reached out to Harry then. That time, though, Harry called me to give the OK on Alex Gibney. (laughs) So I said, “Yeah, Gibney’s a great filmmaker.” So, he did an audio interview for Gibney, and in that audio interview, he talked about Sammy. (laughs) So, I went to Gibney’s people and asked if I could get that audio interview. (laughs) And that’s where I got it from.

HtN: That’s great! So, in your film, I love the section where we see and hear Sammy’s impressions. I had no idea he was such a gifted impressionist.

SP: Gifted.

HtN: He’s amazing! His Humphrey Bogart, his Jimmy Stewart, his James Cagney…

SP: Gifted, gifted, gifted…

HtN: Now, I noticed that you put the titles up on screen of who he’s doing, when he’s doing them. Did you just have fears that today’s audiences wouldn’t know who they were?

SP: Yeah, because generationally, most 20-year-olds don’t know who James Cagney is anymore. They don’t know who Jimmy Stewart is anymore. I mean, they might know who Humphrey Bogart is … But most people don’t know. Initially, we thought that maybe we didn’t need to, but then I realized, well, a young person in their twenties, they’re not going to know. You know, I teach at NYU, and yesterday, I showed, in my class, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. I asked the class, “How many people have seen Breathless?” I have 38 students. 4 raised their hands. (laughs)

HtN: So, you’re right, it’s a generational thing.

SP: (laughs) It’s a generational thing!

HtN: OK, final question. Is there something that you didn’t know about Sammy Davis, Jr., that you learned in the process of making this film that was particularly surprising or noteworthy?

SP: Yes. The pain and rejection of being disinvited form JFK’s inaugural ball. I never knew about that. I never knew that they told him he couldn’t come because he had a white wife. And so, when we were going through those audio tapes – because a lot of the audio is from Sammy’s doing audio when he was writing his autobiography – to hear him talk about that, and the pain of that, was devastating. And think about this, too: his main man, whose running the inaugural ball, Mr. Sinatra…

HtN: Doesn’t fight for him!

SP: …doesn’t fight for Sammy! And that’s his guy!

HtN: And that’s so interesting, because he seemed like a good friend, otherwise, to Sammy.

SP: Yeah!

HtN: But in that moment…you know, something funny happens to people when they get close to power.

SP: That’s right!

HtN: Well, thank you so much. Congratulations on both films!

SP: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)