A Conversation with David Greaves, Liani Greaves, Anne de Mare & Lynn True (ONCE UPON A TIME IN HARLEM)

Once Upon a Time in Harlem is the best film I saw at Sundance this year. It is also, in a sense, a miracle. In 1972, the legendary documentary filmmaker William Greaves—director of the avant-garde masterpiece Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), a film championed by Steven Soderbergh and Steve Buscemi that was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry—assembled the living luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance for a cocktail party at Duke Ellington’s Harlem townhouse. With three 16mm cameras (one operated by his son David), Greaves captured nearly 30 hours of footage as these artists and intellectuals reminisced, argued, laughed, and drank. Greaves considered the party the most important event he ever filmed. He spent the rest of his life trying to complete it. He died in 2014 without finishing.

Now, more than 50 years later and on the centennial of William Greaves’s birth, David Greaves has completed his father’s vision. The result is a staggering work of archival magic—100 minutes that feel like being transported into this room. The guests do not always agree—there are arguments about Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois, about whether the younger generation cares about the Renaissance at all—and that is part of the glory. This is not a dry lesson or a nostalgia piece. It is a party, and you are invited.

William Greaves was born in Harlem in 1926, attended the elite Stuyvesant High School, and studied at the Actors Studio alongside Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, and Anthony Quinn before becoming a filmmaker. He produced over 200 documentary films—including the Emmy-winning Black Journal (1968-1970), Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice (1989), and Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey (2001)—and was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. His wife and lifelong collaborator, Louise Archambault Greaves, dedicated her life to his legacy. She passed away while this film was in production.

The film is directed by David Greaves and produced by his daughter Liani Greaves alongside Anne de Mare, a founding member of Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater and a longtime theater artist who led the preservation and digitization of over 60,000 feet of 16mm footage. The film is edited by Lynn True, who co-directed Albert Maysles’s final film In Transit (2015) and now finds herself completing another master’s unfinished vision. Bill Brand, the renowned experimental filmmaker and archivist, supervised the scanning. At Sundance, I spoke with the Greaves family and the team about channeling William Greaves’s spirit. These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

DAVID GREAVES AND LIANI GREAVES (Director and Producer)

Hammer to Nail: At the 30-minute mark, Richard B. Moore says that the Renaissance was not a development that just took place between 1920 and 1925. He says it goes back much beyond that—there would have been no Renaissance if it was not for people like A. Philip Randolph, the socialist of the 19th Assembly District, and above all, Hubert Harrison. Do you agree with this assessment? And why was it essential to include this in the film?

David Greaves: To show the depth of it. People think of the Harlem Renaissance as Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and these major names, but a lot of it was unsung heroes—people you do not know about, but without whom the Renaissance would not have existed. As Richard B. Moore speaks about, Hubert Harrison was speaking from a street corner ladder. We hear about people speaking from the street corner ladder, but that was the internet of the time. You carry the ladder to the street corner and you address a lot of people. That was the technology he had available to him, and he used it. It was not digital—it was a wooden ladder—and it worked for him. As Moore says, it educated the Harlem population.

HTN: At the hour-and-18-minute mark, Nathan Huggins talks about this marvelous review he read in the Times of Mumbo Jumbo. He says Ishmael Reed and a lot of Black writers have not engaged themselves in doing something that might very well have been impossible for someone to do in the 1920s, which is to address themselves in their art as Black people without concerns about a white critical establishment. He admits that in his own novel, he does not deal with musicians as much as he should. He continues by saying that it is very hard to speak about the Black experience in the English language—the literature and the tradition they are writing in is not really theirs. Nugent strongly agrees. What was critical about having this passage in the film?

DG: Nathan Huggins in his discussion was talking about the difficulty of expressing yourself in the language. You have to remember that this came out of slavery, where you lost your religion, you lost your language, you lost your clothes, you lost the food you ate. Everything was taken away from you. And as he says, music came from someplace else that could not be taken from. That is why the music was the thing that really survived—it brought the Black experience, the Black language, as he says, to the people, to be celebrated. It brought that out. It was the first marker of culture.

People were able to work and collaborate in the language and to examine themselves in the language. Even though George Schuyler did not agree or appreciate it—Arna Bontemps, a writer and poet, says in the film, quoting Langston Hughes, that “we young artists came to be ourselves and speak in our own voice.”

Liani Greaves: They did not all agree with that statement. That is what is really wonderful about the film—they do not all agree. And sometimes that is the way it is, but we can have civilized conversations.

HTN: You would not see a respectful conversation of disagreements like that today, that is for sure. At the hour-and-25-minute mark, William asks Leigh Whipper what the younger generation thinks about the Renaissance. He says, “You want an honest answer? They don’t give a damn. They’re too self-centered.” Richard B. Moore plays devil’s advocate and says maybe we were not sufficient in passing this information down. This leads into him reciting that speech he wrote for the League of Nations. Why was it important to include this moment?

DG: Because he is saying, “gee, is this still important?” And I think the rest of the film does answer that question. It is important—the Renaissance never died. And the speech—I keep referring to Leigh Whipper’s speech, “Highly Slasky”—you have heard that obviously. In cutting it down, I thought: what would Zelensky say? Because the various elements in the speech spoke directly to what is happening today. That is what I was thinking about when I included that.

ANNE DE MARE (Producer)

Hammer to Nail: Before film, you were a playwright—a five-year resident artist with Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater, one of the most experimental theater companies in America. Your video work has been at Lincoln Center and Park Avenue Armory. How does that theatrical background shape how you approach documentary structure?

Anne de Mare: I think it is all storytelling, but I think that the theatrical background, especially experimental film, gives you a sense of freedom. That was really fun on this particular project because Bill Greaves has such energy in his work—such innovation and just freedom to take different kinds of chances. So I think the best answer I could give you is in terms of courage.

HTN: You are a founding member of the Independent Theatre Company, the Nevermore Theatre Project, and Theatres Against War. You have built collectives your whole career. The Greaves family has kept William Greaves Productions running since 1963. What did you recognize in how they work together?

ADM: I basically fell in love with Louise Greaves—that is how I got involved. The Greaves family is an extraordinary legacy. But I think that oftentimes people do not realize how closely families work together. Louise was Bill’s partner in every possible sense of the word, and she dedicated her life to his legacy and to his work. There was something about that that I really respected, beside the fact that she was an absolutely fabulous human being.

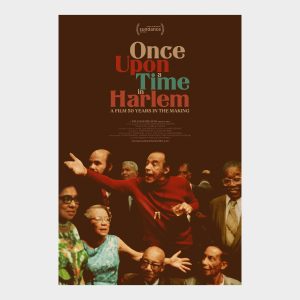

A still from ONCE UPON A TIME IN HARLEM

I had not met David and Liani—I met them when Louise was ill. Meeting them and having the process with them that we have had has been wonderful. Working on this project has been the greatest honor of my life. It has been this model that I think I have been searching for my whole life, where there is no ego in the room, there is no agenda in the room—it is all about the work all the time. That is what brought me into theater, which I love about theater, how democratic it was. That is what this experience has been.

HTN: You worked to preserve and digitize over 60,000 feet of 16mm footage from 1972. What was that archival process like? And talk about working with Bill Brand.

ADM: Bill Brand is phenomenal. There are many layers to it. It was being able to locate and pull all the materials, which were in various different places. Most of the footage itself was in Bill and Louise’s storage unit. The audio was held at the Schomburg. But getting those two things together—putting this together, the sequence of the party, which was shot with four cameras and two different audio sources—was the greatest jigsaw puzzle I have ever worked on.

It took probably six to eight months for us to just get the master sequence of the party, because the way it is shot—as you can tell—things are not slated clearly. It was a beautiful process, frustrating but really fun. I would literally call Bill Brand or text him when one of the moments we could not figure out got figured out, because we both just jumped up and down for joy. It was wonderful to work with Bill. To be able to have someone with that kind of experience to trust with this important material was wonderful. And the scans, as you saw, look amazing.

LYNN TRUE (Editor)

Hammer to Nail: You co-directed In Transit with Albert Maysles—it was his final film, and you edited it. Now you are editing another legendary filmmaker’s final project. What is it like being trusted to complete a master’s unfinished vision?

Lynn True: I feel so lucky. I do not really know how that all happened—both In Transit and this project. Actually, I have known Anne de Mare for over 20 years. I edited her first film way back in the day, and she really just called me up one day out of the blue and said, “I think I have something special that you are the right person for.” So it was just an honor and a joy. I feel very lucky.

HTN: These luminaries are reminiscing, critiquing, arguing, laughing, and drinking. What surprised you most about the dynamic in that room?

LT: That all of the arguing, debate, conversation and reflecting was so substantive—and brutal but polite at the same time. There was this quality of respect and understanding that unfortunately is very rare today. They actually wanted to have these conversations and push each other to think about these issues and topics and subjects that happened so far before this party, in a real and substantive way. I am at a loss for words, but it was really refreshing and wonderful to see actual respectful adult debate. They were fighting, but at the same time, it was for a reason. It was not just to critique and cancel each other.

HTN: You were guided by David Greaves and William Greaves’s own notes and work prints. How prescriptive were those materials, and how much room did you have to bring your own editorial vision?

LT: Ultimately it really was trying to channel the spirit of William Greaves. This is material that he shot, and I was made very aware from the get-go how important this project was to him. David knows him so well and was obviously the perfect person to see it through now. But they gave me a lot of space to just sit with the material and really get a feel for it. It is not my generation—it is not something that I was very familiar with. I worked chronologically on the first pass, from the party’s beginning to end. Then we all worked together from there in rearranging it, refocusing it.

It is a deceptively simple concept—one location, a three-hour party. But the final film is not a straight chronological rendition of that time and space. It really was about the rhythm of allowing these important references and moments to sing without overthinking them. This is not a movie about the history of the Harlem Renaissance. It is not supposed to be a retelling of why this happened and who these people exactly were. It was more of a feeling—remembering them, seeing them, and all the people who gathered to remember them, seeing each other again in those terms

HTN: You studied architecture and urban studies at Brown. This footage was shot in Duke Ellington’s townhouse, a specific Harlem interior in 1972. How does the architecture of that space shape what you see in the footage?

LT: I think it is so important—just the colors, how you navigate. There are basically two main rooms in the party and a hallway that connects them. To me, navigating those spaces and understanding how those relationships were unfolding in the corners or at the punch bowl—all of that really contributes to a viewer’s sense of authenticity and feeling like they are in the space as well. We are not just cutting to the cutest shots back and forth. We are really trying to allow you to feel like you are wandering around that party yourself.

The architecture and the layout and the landscape of that space—for me, that is always important in a film, but this one in particular because it was not a very big space. That is something I spent a lot of time hoping to air out and allow to wash over you, so you would understand it even subconsciously.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)