A Conversation with Joshua Z. Weinstein & Menashe Lustig (MENASHE)

I spoke by phone with filmmaker Joshua Z. Weinstein, on Monday, May 22, 2017, about the making of his narrative feature debut, Menashe (which I reviewed, as well, at the Washington Jewish Film Festival). A thoughtful meditation on love, grief and group identity, the film was shot within Brooklyn’s Hasidic community in Borough Park, starring Hasidic non-actors in most parts, all speaking Yiddish (the film comes with English subtitles). One of those actors is Menashe Lustig, who plays the title role, whose own life story serves as inspiration for parts of the plot. Within the movie, Menashe is a widower struggling to raise his son in a community that holds little respect for single-parenting. Mr. Lustig joined in the conversation, as well. Here is a condensed digest of our chat, edited for brevity and clarity.

I spoke by phone with filmmaker Joshua Z. Weinstein, on Monday, May 22, 2017, about the making of his narrative feature debut, Menashe (which I reviewed, as well, at the Washington Jewish Film Festival). A thoughtful meditation on love, grief and group identity, the film was shot within Brooklyn’s Hasidic community in Borough Park, starring Hasidic non-actors in most parts, all speaking Yiddish (the film comes with English subtitles). One of those actors is Menashe Lustig, who plays the title role, whose own life story serves as inspiration for parts of the plot. Within the movie, Menashe is a widower struggling to raise his son in a community that holds little respect for single-parenting. Mr. Lustig joined in the conversation, as well. Here is a condensed digest of our chat, edited for brevity and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, first of all, I want to start with your experience leading up to the making of this film. You are primarily a documentarian, as I understand it, and you even shot part of a film, Don’t Stop Believin’: Everyman’s Journey, by a Baltimore-based director I know, Ramona Diaz. Could you talk about your experience before making Menashe?

Joshua Weinstein: So, for the last dozen years, I was primarily a documentary cinematographer. I shot everywhere, from India, the Philippines…for two different projects with Ramona…shot with Morgan Spurlock, Amanda Micheli and like 10 different Oscar-nominated documentary directors. And what I love about documentaries is that you don’t have to be bogged down by big crews and lots of money to make a movie.

So that’s what originally got me excited about documentaries, but as an artist, myself, I also found it lacking, because it’s hard to have control, and control is where art comes from. Having a vision and then creating what that is. For me, I’ve always been really inspired by De Sica, Satyajit Ray and the Dardenne brothers, and Kelly Reichardt, and just all the ways that people have used the best parts of documentary and then captured incredible films from that. So, as an artist, that’s where I want to push myself and what I want to do, because as much as I love documentary, I always felt that I could never fully achieve what my visions were. No matter how brilliant you are at documentary, there is a certain amount of luck involved.

HtN: Right, but parts of your film feel as if they were shot documentary-style, so perhaps there was some luck involved there, as well?

JW: No. Nothing was shot like a documentary. There is no documentary at all.

HtN: What I mean, though, is that it seems as if some of the shots on the street are maybe done on a telephoto lens. I don’t know if you were hiding the camera or not, or if everything was staged. It just struck me that some of the shots looked as if they might have been done in that way.

JW: Well, you know, we couldn’t afford 200 extras, so we definitely shot in the street with big plaque boards that said, “By walking through this street, you are agreeing to be in the movie,” which people do in New York City all the time. But as far as a lot of the camera techniques go, I just really wanted to do really long takes. And there’s something about working on a 400mm lens, or having a shot that lasts over a minute, where you just feel the authenticity. It makes you feel that reality is happening before you.

HtN: Sure. So, leading up now to the inspiration for this particular story, I was happy to see in the movie’s credits the name of a man I met last year at the SXSW Film Festival, Musa Syeed, whom I interviewed about his great film A Stray, and I thought he was an interesting partner to have on this project, because he is a Muslim-American filmmaker. So, I was curious both how you came up with the idea for this movie, and how you ended up partnering with Musa.

JW: So, I’ve know Musa, from the documentary world, since I started out, and Yoni Brook – who was a producer, and co-shot the film with me – shot all of Musa’s films, and they directed two documentaries together, as well. So I’ve just known Musa and Yoni for a long time. What I loved about Musa was: a) how he made films that wrestled with religion – obviously, his are about Islam – that were about characters who were dealing with religion and trying to find their place in that society; and b) he, like me, comes from documentary and understands the poetry of everyday life. For me, I want to make films that are about these moments, and the plot is just the glue that holds everything together. I don’t make films for the plot; I make films so I can see thousands of people together in front of a big bonfire.

HtN: So what then made you choose to set the film in the very insular Hasidic community of Borough Park?

JW: So, I worked all over the world, as I said – in India, in the Philippines – and it’s so easy to point the lens at another country and think, “Oh, here’s something exotic, here’s something different,” but what I love about New York City is that there are immense differences just a few blocks away, and the whole unknowability of ultra-Orthodox people just made me excited, because no one had ever made an authentic film about this community.

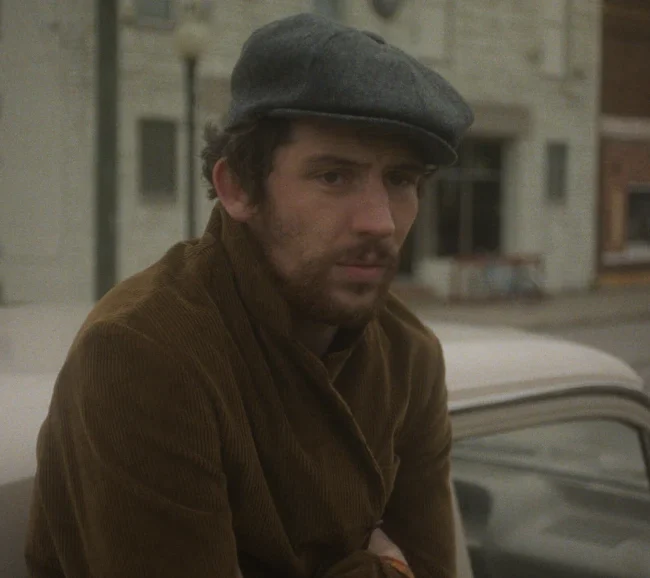

HtN: So, you have this great actor at the center of your movie, Menashe Lustig. How did you find him and what did you take from his life as the basis of your story?

JW: So, this film is literally a lucky moment in time. There are so many reasons that this film could have fallen apart and never been possible to make. While we were doing casting, we were only able to get about 30 people to come out for the casting, who spoke Yiddish and were ultra-Orthodox. When I met Menashe, I was right away captivated by this Charlie-Chaplinesque persona of his, but there was also this sadness and brokenness in his eyes. I just love characters that are not 100% beautiful. I want someone whose heart feels a little damaged. His eyes told everything, and I just knew that Menashe could carry the entire film.

HtN: So, Menashe, how do you feel about being categorized as not 100% beautiful?

Menashe Lustig: (laughs) I tell you what, I really appreciate that I made the project in a serious way. People in my circle know me as a comedian. I was born with this talent to be funny, but my real talent is as an actor of all kinds of emotional ranges. I close my eyes, and I can imagine being anywhere, doing anything. So people know me as someone who does funny stuff, because people like funny stuff, but know Josh made a project that was very serious, and I liked that, because I like acting. Not every action is a joke. Not everything is a joke. Life is serious. But even if I say life is not a joke, life needs jokes. (laughs)

HtN: So, how much of the story of your character in the film is taken from your actual life, and how much is the fantasy of the scriptwriter?

ML: It’s based on my life. A lot of things happened in my life that were very similar, and when I watched the film in the theater, it all came back to me. I’m a very emotional guy, so the anxiety that I felt then came back to me. Which means that when I was acting, I also felt all of these emotions. Yes, it’s very similar to real life.

JW: So, it’s 100% the emotional truth that Menashe lived. That was the goal, to try to share those feelings on the big screen. And the actual truth about Menashe’s life is that he really is widowed, and he really does not live with his son. Those are the only factual parts. Everything else was me, Musa and [other screenwriter] Alex Lipschultz imagining how we could make that into a dramatic film that would last 82 minutes. But, you know, because we were working with non-actors – Menashe is brilliant, and could be in any movie he wanted to be – we really tried to just find out who they were and change the part to be them.

For example, originally we wrote a father-in-law character to be the main villain in the movie, but then we couldn’t find a father-in-law – well, we cast a great father-in-law, but he quit a few days before filming – so we made him a brother-in-law. The actor who played the Rabbi was a taxi driver in real life, who went to Rabbinical School, who always wanted to be a Rabbi, so we were able to play off how he thought a Rabbi should act. And the boss in the grocery store was really a boss at a printing press. (laughs) So, you know, they were all figuring out who they were, and we were just changing our film to work with them, because at the end of the day, we made every sacrifice possible to make sure the actors were great. We knew if the performances were amazing, then people would forgive any other issues with the movie.

HtN: I think you’ve cast very well, and watching the film, I wasn’t aware that these were non-actors. The performances were rich, Did you ever consider casting outside the Hasidic community for any of these parts, or was it really important to you to stay truthful in that way?

JW: This film took over a year to shoot and produce – maybe a year and a half – because we spent so much time making sure every detail was authentic, from the locations, to the costumes, to the biblical passages, to the right Yiddish words being used, so things that would take 10% of the time, took us, instead, days and weeks and months to get right. If we had had money, maybe we could have found some Yiddish actors and put fake beards on them, but I think we were rewarded by our labors.

HtN: I understand. Do you speak Yiddish, yourself?

JW: No. We blocked all the scenes in English, first, and then once we started recording we switched to Yiddish. That also allowed the non-actors to be in the moment again and talk in their mother tongue, which was just more comfortable and natural for them. And then we had a translator in another room, who would live translate into the producer’s ear, and then I learned enough Yiddish that I could basically understand what was happening, and when things were way off-book, we obviously corrected them, though we did allow the actors to improvise, slightly, like in a Cassavetes film.

HtN: So the purpose of that live translation was just to monitor that they didn’t too far off-book, but you weren’t too concerned, otherwise, with line improvisation?

JW: There were enough lines where we said, “You have to say exactly this, in that moment,” but overall, we wanted people to feel comfortable. When they were comfortable, and authentic, it made the film better.

HtN: Final question: Menashe is not always a sympathetic character. You talked about him not being 100% beautiful, and having a protagonist who doesn’t always do the right thing is more interesting, but there are times in his interactions with his son, where one wishes that he would maybe be nicer to him in the same way one might wish that other people would be nicer to Mensahe. Were you ever tempted to make him nicer? How did you develop that character?

JW: This is a film about somebody dealing with grief, and grief affects you in so many different ways. And also, this is a community that so many people do not understand, and it’s human nature to do the wrong thing. People get angry with their children. If Menashe was just a doting, loving father, that wouldn’t be human. (laughs) That doesn’t feel like anyone I’ve ever met, or known. The complexities of grief affect us all differently, so I was just interested in how this grief and how this guilt had affected Menashe.

ML: When you have anxiety, your mind is not entirely here. You do strange things. You mess up. You can’t blame yourself, either. That’s the situation, and the price of the challenge.

HtN: Gentlemen, thank you very much. I wish you success with the film.

ML/JW: Thanks!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)