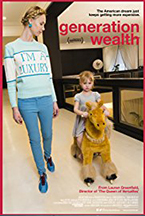

A Conversation with Lauren Greenfield (GENERATION WEALTH)

I met with director Lauren Greenfield, of the new documentary feature Generation Wealth (which I also reviewed), on Sunday, March 11, at the 2018 SXSW Film Festival. The film discusses the wages of capitalist sin over the past quarter-century, chronicling the trends in excessive consumption and compulsion that have formed the cornerstone of Greenfield’s work during that time. In the movie, Greenfield revisits her past photography and documentary projects – including the 2012 The Queen of Versailles – using the material to present a damning condemnation of Western civilization in all its rapidly fading glory. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for clarity.

I met with director Lauren Greenfield, of the new documentary feature Generation Wealth (which I also reviewed), on Sunday, March 11, at the 2018 SXSW Film Festival. The film discusses the wages of capitalist sin over the past quarter-century, chronicling the trends in excessive consumption and compulsion that have formed the cornerstone of Greenfield’s work during that time. In the movie, Greenfield revisits her past photography and documentary projects – including the 2012 The Queen of Versailles – using the material to present a damning condemnation of Western civilization in all its rapidly fading glory. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, this film, Generation Wealth, is more than just a movie. You released an accompanying monograph in 2017, and then you had an exhibit. I read that you edited the film for about 30 months. It is quite the summation of your life and work. At what point, in all your many projects, did you decide to embark on this particular movie?

Lauren Greenfield: Well, I hate to call it a summation, because I do feel like I’m kind of in the middle of my work. (laughs)

HtN: I apologize for the word!

LG: But, that being said, it’s unusual to look back so intensely at this period of my life, because I’m not done working, or anything. I’m in the middle. But I did it because I felt like now was the time that this theme had to be expressed. I realized, in 2008, when the crash was happening, that I had been looking at excess in a lot of different areas, particularly in the late-stage capitalism excess of money and how that became a part of the housing crisis and eventually of the financial crisis, and when the crash happened, it turned everything into a morality tale.

That made me want to go back and rethink what I had seen, because it had become a story with consequences. I started, at that point, looking back and seeing if maybe all of these different stories that I had done – on different subjects and different themes – were somehow related, and told us a story about who we were at this time and how we have changed. And so, I started at the time of the crash, but really when I finished The Queen of Versailles – my last film, about a family building the biggest house in America…

HtN: Which I loved, by the way.

LG: Oh, thank you! So, I decided it was time. This was not about the 1%, this was not about this rich family, it was really about all of us. My work had been looking at how it was about all of us, and so I felt like I needed to go back and reprocess that with the new perspective of this story, and with the perspective over time, because what became clear, as I started to go back, was that these 25 years of work weren’t just the years I happened to work and the personal path I was on, creatively, but it was actually this kind of photographic evidence of how we had changed as a culture.

A lot of the things that were touchstones for me kind of started in that time – the late ’80s and early ’90s – when I began to work. So, I started to think about how and why we had changed. And basically, from the last 5 years, I was full-time doing this, and it started as a book, and I didn’t want to make a movie. I really resisted making a movie for a long time, because I think I kind of knew it might be a personal movie, and I didn’t want to make that, or it might be an essay movie, and I didn’t want to make that, either. But I just realized that I had to make the movie, at a certain point.

HtN: And it is a personal film, and it does have qualities of the essay film…

LG: Yeah! (laughs)

HtN: …and that’s fine!

LG: Well, what I ended up doing, in a way, was a kind of hybrid, where I made up my own. It’s not a traditional essay film, in that it’s character-driven and personal. And it became a personal film as the essay drew me in, in a kind of organic way. And I just felt, especially with the rise of Trump – which was at the end of this journey – that I needed to take a rigorous look at the culture that had brought us here.

HtN: Sure. May I ask a question that I wasn’t going to ask, but since we’re talking about The Queen of Versailles, if it’s it not taboo to talk about a previous film…

LG: Well, it relates to this.

HtN’s Chris Reed and filmmaker Lauren Greenfield

HtN: It does! And those subjects are in this film, as well, since you use footage from that…But I read, after Queen of Versailles came out, that there was some contention between you and your subjects, who felt that this was not how they thought they were going to be portrayed…

LG: It’s a little more complicated than that. It’s a really interesting story. So, the two protagonists – Jackie Siegel and David Siegel – felt very differently about it. Basically, Jackie Siegel, when it premiered at Sundance, in 2012, came to the premiere, blew kisses to the audience, did the red carpet, and then went on to promote the film…

HtN: I can imagine! I have an image in my head of her doing that.

LG: (laughs)…and she went on to promote the film with me all over the world, through the TV release, which was more than a year later. At the same time, her husband, David Siegel, sued Sundance, and myself, over a line written in the Sundance brochure that said it was “a riches to rags story,” which he didn’t realize at the time, since he hadn’t seen the movie, was actually a quote from him in the movie. And I think even David Siegel had mixed feelings about the film in the sense that he bought out a theater in Florida for his friends, and brought them all there on a party bus and introduced the film, and said it was a really good film, but none of it was true. (laughs)

And then Jackie still loves the film, and the experience, and wishes we could do another one, and has come to all the Generation Wealth shows. So, I think, for David, it was all about business. He said he really liked the film, but just hated the ending, where he loses Vegas. That’s not where he wanted to end the story. He wanted to end the story where he is now, which is: business is back, and they’re supporting Trump. But that wasn’t the story that I was telling.

HtN: Right – in this new film, you have that image of them behind Trump at a rally, which makes it very clear that they are probably enjoying this new world.

LG: Yeah! A little bit of postscript there. I think one of the realizations, for me, in making Generation Wealth, is that the financial crash seemed like it taught us all these important lessons about how we had been living, and it seemed like people were changing. Even David Siegel says, “I shouldn’t have built so big; live within your means. I should have been happy with fewer resorts, and then this wouldn’t have happened.”

And yet the postscript of that story is that, as soon as he could, he borrowed the money to get the house back, and now says he’s going to finish the house, even though we’re 7 years later, and it’s not finished, and he’s well into his 80s, now. So, in a way, it’s a sort of disappointing – or disillusioning – postscript to the crash, but one that also made me think about addiction, and how ingrained these ideas are in our culture, and whether there is the possibility for change and agency.

HtN: It’s interesting to me how you draw a parallel between the addiction to money, plastic surgery, porn, and all other forms of addiction, and to your own workaholism. That’s a fascinating aspect of the film. I take mild exception, though, to this idea that somebody who is creatively obsessed, as you are, is equal to these others. Perhaps it’s my own bias – and I put that in my review of the film – because yes, you are obsessed, but somehow…(laughs)…I see that as a more noble obsession, in a way, because it’s to a purpose beyond yourself.

LG: Well, I’m not trying to say that they’re equal. I definitely feel that there are some addictions, which are life-threatening – like having an eating disorder, for example – or a mental illness, and I don’t want to trivialize any of those experiences by suggesting that they’re equal. But, one of the things I tried to do by including my journey, is to show a little bit about the person – and filter – seeing this. And I think I can relate.

I mean, one of the things I have done in my work is that I’ve always gone after subjects that I could relate to personally. For example, when I was in high school and college, I was a chronic dieter, but I’ve never had an eating disorder. I’ve studied the causes of that, and I think I don’t have certain triggers for that. But I have enough of the normative part that I can relate to the pathology.

A scene from GENERATION WEALTH

HtN: I guess I mostly objected to the idea of comparing yourself to one of your subjects, disgraced former hedge-fund manager Florian Homm, who in many ways is obsessed with all the wrong things. That’s what I meant.

LG: Right. On the other hand, I also wanted to address the fact that there are consequences. And even in my own choices, even though there are benefits, too, there are also consequences for my family. My husband would say that it is like alcoholism, or like the guy in the bar…The fact that it’s positive or negative, or having that kind of value judgment on it, doesn’t really replace the fact that it’s still something that is out of your control, and has consequences.

HtN: It’s compulsion, no matter how you choose to spin it.

LG: And it also has a kind of hereditary or socialized aspect to it. I was also looking at how these things are passed down through generations.

HtN: Speaking of which, I love your interview with your mother. It was really moving. I enjoyed the conversation you had with her. And then, of course, you include your children, although your husband seems to be a little camera-shy, compared to everyone else. I don’t know if he just didn’t want to be in the film, or if you chose not to put him in. But what reservations, if any, did you have about including your kids and your parents?

LG: I mean, it was not intended as a personal film, and I think my editors were interested in doing that, and kept trying things out, because I think that they knew, and rightly so, that narratively, it kind of needed a center. It needed me as the connective thread, because over the past 25 years, the subjects I have gone after are so disparate and different and stretch into so many different areas. For me, it was really important to tie it together, so that there is a connection between the objectification of women, the commodification of human beings, the economic crisis, the materialism of hip-hop…all of these things are connected, as is the post-Communist world and how it has taken on the values of capitalism. So, for me it was very clear, but I realized that I first had to explain the connections. So I was in there, from the beginning, as a kind of narrator.

So, my editors kept trying the personal stuff, and I really resisted it, because I come from a background of reportage, of vérité. Also, I’m doing a film about narcissism, and I didn’t want to then put myself in the center of it. But it kind of naturally happened. I started with interviewing my parents and my kids as, in a way, representatives of their generations: to talk to my parents about the American dream and the 1970s, and how we’ve changed; to talk to my kids about social media and what it’s like being in this environment.

But, inevitably, in my work, things become very intimate, and that’s how I kind of always am with my subjects, pressing and pressing. And so, when I pressed with my parents and my kids on things I did want to know, the answers I got were sometimes upsetting and disturbing, but led me in a different direction. And then at that point, I felt that I had taken such an intimate lens on other people, and asked them to be so vulnerable with me, that I had to be willing to do that with myself, and it really came together, for me, with what [interview subject] Chris Hedges says at the end, when he says that culture is undermined by the values of corporate capitalism, and that it’s really culture – authentic culture – that gives us the possibility of criticizing ourselves. And that’s really why I’ve been doing this work for all of this time.

HtN: Right. I like Chris Hedges’ interview a lot. And I really do appreciate that you keep those difficult questions and answers in the film. I think it’s really powerful for that reason. So, I have a question about how you found some of your subjects. I don’t need to guess how you found this sad former porn star/stripper Kacey/Courtney – whose name keeps changing – since she was in the news. For me, she is one of the two saddest stories in the film, her and the woman who gets plastic surgery, whose name I forget…

LG: Cathy.

HtN: Heartbreaking stories! So, I’m curious how you found Cathy and someone like Suzanne, who has, in some ways, one of the happier trajectories, finding better values at the end. How did you find your subjects?

LG: Cathy, Suzanne and Kacey…

HtN: Is Kacey what she’s going by now?

LG: No. She’s going by Courtney now. I found all of them from photo assignments, through my work as a photo-journalist. In a way, that’s how I’ve found all my subjects, including Jackie Siegel from The Queen of Versailles. So, with Cathy, I researched it, myself, in the sense that, whenever I’ve worked on a project, I’ve self-assigned a lot of stories. So, I was working on a project about aging, and how aging is changing, and was looking for women going to Brazil for plastic surgeries: plastic-surgery tourism. I was really interested in how this was something that had been a luxury, but was now for the middle class and working class. 75% of women who get plastic surgery make $50,000/year or less.

So, I was looking for women who wanted it but couldn’t afford it in the U.S., and were going elsewhere, and I think I found her through a concierge company. I proposed it to a women’s magazine, and they didn’t end up publishing it, I think, because there were several women I meant to follow, and one of the others didn’t come through, and was slightly more glamorous than Cathy. But Cathy was really intriguing to me and I stayed with her, because she was a working-class woman – she was a bus driver, a single mom – and this was so important to her. And I was really interested in this idea of the makeover as this kind of new American dream.

So, I found her, originally, for a story that never got published, which is actually the story of a lot of stories. When I made Thin, about eating disorders, I first went to the location for a story for Time Magazine that was never published. But I try to keep my own mission, so it doesn’t matter if it fails for a magazine, or their agenda changes. I often go back to the things that I’m interested in. With Cathy, I went back to her again, in 2011, when I was making a film called Beauty CULTure, and that’s when she told me the story about her daughter cutting herself. And it was only in the process of reaching out to her for Generation Wealth that I found out that her daughter had passed away. That was so shocking, because what was burned into my brain were these last words she’d told me about her daughter cutting herself with the word “dead.”

So, that was kind of my process in this film: touching base with a lot of people I had talked to over the years, who had been important in my work, and checking in with them. So, the people I stayed with are the people whose stories really expressed the bigger “Generation Wealth” narrative.

HtN: Well, it’s a really fascinating mix of people. I really enjoyed the film. Congratulations.

LG: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)