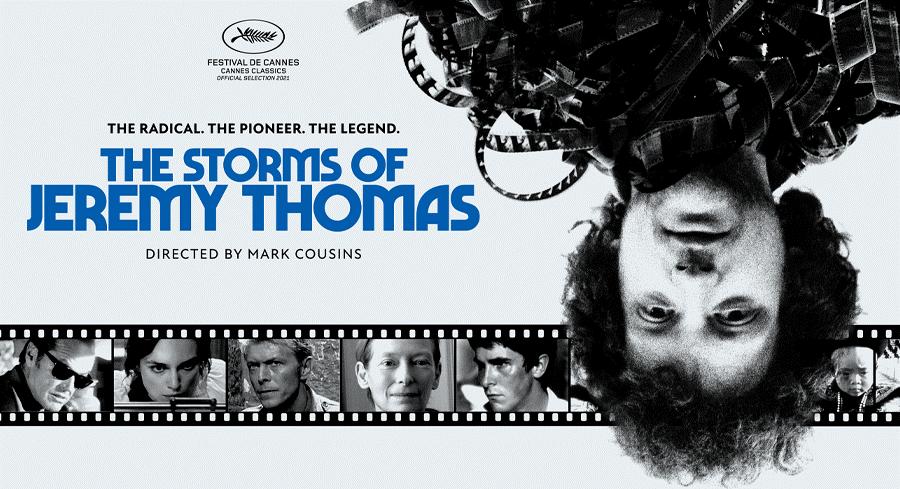

A Conversation with Jeremy Thomas (The Storms of Jeremy Thomas)

The career and life of veteran producer Jeremy Thomas is profiled in Mark Cousins’ new documentary The Storms of Jeremy Thomas, now playing in theaters from Cohen Media Group. Thomas has produced dozens of films for almost five decades, working frequently with filmmakers such as David Cronenberg, Bernardo Bertolucci, Nagisa Oshima, and Nicolas Roeg. He produced Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor which won the 1987 Academy Award for Best Picture. I had the pleasure of chatting with Mr. Thomas about his vast career, growing up in the film industry, his relationships with filmmakers (as well as cars), and exciting future projects.

Hammer To Nail: So Mr. Thomas, first off I want to say congratulations on your retrospective this weekend at Quad Cinema!

Jeremy Thomas: Yeah, it was very nicely done. I can’t wait to see them on the big screen…again.

HtN: How’s it been reliving your long career with that and this documentary?

JT: Well I’ve been entombed with filmmaking my entire career– my life since I was 17. I grew up in the movie business because my dad was a filmmaker. It’s been a very interesting journey making films, especially if you make them principally on-location in other countries. It was a different time when I started making films. It was much easier than it is today. I’m pleased to see my work down at the Quad.

HtN: How did you and Mark Cousins get together and decide to tell your story in The Storms of Jeremy Thomas?

JT: I’ve known Mark for a while now, and I’ve seen his other documentaries on cinema. He asked me to join him on his road trip. His producer David P. Kelly approached me and asked if they could capture my trip to Cannes. We’d talk about movies, and I thought it was a nice idea. People have asked me about making documentaries before, but it’s very academic in terms of how to make films. When this idea happened, I thought it was nice that I didn’t have to do anything. I just drove the car. I really didn’t have much to do for the film, except for a week he drove me, photographed, and recorded stuff. From there, they would juxtapose the images with old films of mine.

HtN: This documentary sort of plays like a road movie, in a sense. How was it for you two to hit the road together? Even when you were off-camera, what was that like?

JT: I do love a road trip movie. It’s one of my favorite things to watch, but I do love driving very much. I do like a beautifully made automobile. It’s a form of transport that’s closer to the earth than a train or airplane. I’d rather ride in Europe where I don’t have an agenda in the normal sense, and you can just move around like that carrying stuff between London, Paris, and Rome. Then I’ll leave the car, fly home, and then later I’ll go back and pick it up. I’ve been using that mode of transport all my life. Sometimes it takes longer to fly to Paris than it is to drive there.

HtN: How did you feel when Mark addressed you as a “prince” in the documentary?

JT: I think the reason Mark called me that is because I’m a second-generation filmmaker. My dad [Ralph Thomas] was a film director who was a very strong figure in the British film industry. My Uncle Gerald was also a successful director. Mark describes them as emperors, and they were brothers who were a big part of the film industry, which can be like an empire. So I think that’s what he was referring to. I’ve been in this business for about 50 years.

HtN: Congratulations!

JT: That’s a long time. I started out as an assistant editor, then an editor, producer, and director. But producing, principally, has been my career. For good or bad, my taste has been used as a barometer for what I did. Now it’d be an unusual idea to do it, but I’m still doing it and it’s wonderful.

HtN: You directed one movie back in 1998, All the Little Animals. Would you ever consider directing again?

Filmmaker Jeremy Thomas

JT: Yeah I would. I think it’s a wonderful job. It’s the best job, probably. I directed that film because I wanted to tell that story since I was young. I took a year off from my main work and made this film with Christian Bale and John Hurt. It was a story that came from my passion for animals and nature. It was very enjoyable. It went to Cannes and I was very satisfied, even though it was a very naive kind of film. I’m very happy to have done it. I’m not currently looking at anything to direct, but I would like to try again because it’s a wonderful exercise. Everybody wants to direct, you know?

HtN: I’m curious, what attracts you to a film you’re interested in producing? Are there certain criteria you normally use when finding the right projects for you?

JT: The criteria are in my mind, really. I think it’s a matter of liking or not liking the subject, and the combination of those involved in making the film. I like to think about what the film can be, what I can promote to get it seen by people, and if I can get it into the main selection of a film festival. I’d want the film to move me and make me want to see it. It also has to do with the people involved. I want to build relationships with the filmmakers. As you can see in my filmography, I’ve worked multiple times with a bunch of people. After you’ve worked with somebody and you have a good time, you will have a better time with their next film. I’ve worked multiple times with Nicolas Roeg, Nagisa Oshima, Bernardo Bertolucci, David Cronenberg, etc. I’ve worked on maybe 3-5 films with each one. Those people have been very faithful to me, and I want to be faithful to them.

HtN: You sort of have this reputation as a producer of provocative, boundary-pushing cinema such as Crash and The Dreamers. Do you ever know or feel when a film is bound to hit a nerve ahead of its release or premiere?

JT: Well, I knew that Crash was going to be a very strong film. [David] Cronenberg’s a master filmmaker, one of the greats. When we first showed it at Cannes [in 1996], it was a reaction that I had never seen. There were over a hundred journalists going crazy over it. It was actually very satisfying because we had this film premiere in the main competition and there were all these seasoned professionals provoked. I didn’t know the reaction was going to be that bad over an adaptation of a J.G. Ballard book. It was banned in the U.K. and I don’t think that anyone who’s been in a car crash has seen Crash (laughs). I think it’s more of a precautionary tale.

HtN: As an admirer of cars, did your heart break for all those unfortunate cars that got wrecked in Crash?

JT: Yeah it was sad, but they were a little wrecked up before we wrecked them more (laughs). I have kind of a love/hate relationship with cars.

HtN: The first time you worked with Cronenberg was on Naked Lunch in 1991. I need to nerd out a bit here: What went through your mind the first time you walked on set and saw all those mutated bugs lying around?

JT: Well I met David in 1982 and he told me he wanted to adapt Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs. I think he’s the only person in the world who could do something like that. I thought it was very brilliant, seeing how he adapted the text. The whole set looked amazing. I would very much love to work with David again.

HtN: Have you thought about working with his son, Brandon?

JT: Yes. I love Brandon. He’s very interesting. Keeping the family business alive!

HtN: I’m curious about the relationship you had with Bertolucci. You worked on five films together. Each one is sensual in its own way, but also different in terms of scale and scope. Did you two have a shorthand in terms of how you collaborated, no matter how big or small a project was?

JT: Yeah we did. We became best friends and our lives were intertwined. The Last Emperor was such a big experience and it resulted in us becoming close to one another. That film was a massive enterprise as well as The Sheltering Sky which we shot in Africa. Little Buddha was a massive exercise, which was shot in Nepal. These films were all big experiences and challenges. They were a high point in my career and it took massive resources to get them made. Making the films was difficult, but finding the resources was easy. [Bernardo] taught me a lot of things about cinema and life. He was a great collaborator.

HtN: The Storms of Jeremy Thomas draws an interesting line between sex and politics with some of your films. Are those two themes you usually like to have implemented simultaneously in your work?

JT: Well everyone’s either involved in politics or has their lives dominated by it, especially by the political class. Geopolitics is important to me as well. Sex is an important part of our lives and I’m prepared to make films that deal with that subject. I want to have it shown in the right way. I’ve dealt with it in lots of ways in different films. I didn’t direct those scenes, but I’ve been involved with people who’ve been very happy to deal with that in an elegant way.

HtN: Any projects you’re currently working on?

JT: (Smiles) I never stop working. I’m working on a few movies. I produced Viggo Mortensen’s The Dead Don’t Hurt which recently premiered in Toronto and that’s coming out soon in my home. Then I’m preparing a film about Billy Wilder that’s based on the book Billy Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe. We hope to start shooting next April. The great master filmmaker Stephen Frears is directing it and it’s being written by Christopher Hampton who wrote Dangerous Liaisons. The book it’s based on is about a girl’s voyage through life, meeting Billy Wilder, and getting to work on his films.

HtN: If people were to have a marathon of all your produced works, is there one particular thing you’d want them to take away from it?

JT: Well at the end of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, there’s this scene where the sergeant of the war camp, played by [Takeshi] Kitano, is in the English prison war camp waiting to be executed for the crimes he committed. He says “I don’t understand, my crimes are no different from any others.” Tom Conti’s character says “You are a victim of men who think they’re right. Just as when we were prisoners, we were victims of men who thought they were right. But ultimately, in the end, nobody’s right.” It was so powerful and I was happy to make that anti-war movie. I’m still moved by the end scene. So I hope that people have a profound feeling or are entertained by them. It’s very unusual for somebody to link the films together in regards to the producer, especially when you’re still alive. I still don’t know how I did it all, but I still love being on the road and making films.

HtN: I hope you keep at it for sure.

JT: I want to keep making beautiful and provocative films. Some other films I like to watch, but they’re not for me to make. Making films is a difficult process and you have to stay committed to it. It’s like a long conveyor belt, you can’t get off it until it ends. You cannot stop until it’s finished.

– M.J. O’Toole (@mj_otoole93)