A Conversation with Ira Deutchman (SEARCHING FOR MR. RUGOFF)

Longtime film producer, distributor and marketer (and Columbia University professor) Ira Deutchman steps behind the camera for his first feature-length documentary as director to tell the tale of Don Rugoff, who once ruled the art-house movie circuit in his heyday. The resulting film, Searching for Mr. Rugoff (which I also reviewed), is filled with fascinating material on the ins and outs of independent distribution in the 1960s and ‘70s, from archival footage and stills to interviews with important directors like Robert Downey Sr. (now deceased), Costa-Gavras and Lina Wertmüller. Deutchman also steps in front of the camera as a character, since he once worked for Rugoff and brings that experience into the narrative. Whether one is a cinephile or not, the documentary holds something of interest for everyone. I just recently had a chance to speak with Deutchman by Zoom. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: When did you first start working on Searching for Mr. Rugoff, and about how long did it take you from start to finish?

Ira Deutchman: I think that the total process is probably close to seven years. It’s a little misleading because in the early years I wasn’t necessarily serious about making a movie. I was ruminating about trying to tell stories that had to do with people from that generation – the generation that came before me in the film business – and what brought that on was just running into a lot of folks at film festivals and realizing that a lot of the people in that generation were getting old and they had these really great stories to tell, and I wanted to capture it.

There was an evolution that happened over a couple of years where there were other things that were in my mind as possible ways of dealing with this. Maybe it was an oral history, maybe it was a book, but then a couple of things happened that sort of set me on this as being the subject matter, when I suddenly realized, “You know what, I know at least part of this guy’s story. I feel like nobody else does, and that maybe this is what I should focus on.” Once I started taking it seriously, I would say that I was shooting for around three years and it took about a year and a half to edit and get it ready for the marketplace. Then, of course, we had this year-and-a-half delay between its first film-festival showing and the final release of the movie because of this little thing called COVID.

HtN: What’s that?

ID: (laughs) Exactly.

HtN: What made you want to step behind the camera as a director for the first time? Obviously, you have a long and storied career as a producer, distributor and marketer, but, at least according to IMDb, this is your first time as a director.

ID: To be clear, this is my first time directing since college, but yes, I never had an aspiration to direct and I still really don’t. This was just one of those stories where I felt like that there was nobody else who could tell it. As it developed, I had very clear ideas about what I wanted to get across, and why this guy’s story was important. It’s just one of those things. I don’t think I could have gotten somebody to pay the kind of attention to it that I did over that period of time. I certainly couldn’t afford to hire somebody to do it, so by default I kind of became the director.

Interestingly, the more important decision that was really hard for me was, once I launched into it, whether I was going to appear in the movie or not, which I really didn’t want to do. I was thinking about every way of telling the story that could avoid my actually being in the film, and realized over time that there was no way to avoid it, because I was one of the youngest people who worked for the guy who still remembered things. In order to connect the dots of all these various people, and various worlds that I’ve dealt with in the film, there was no doubt that I was going to end up having to be the connecting tissue. That was tough. I really didn’t want to be in the movie.

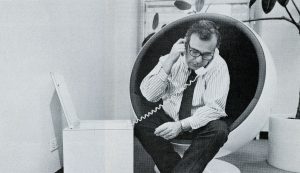

a still from “Searching for Mr. Rugoff”

HtN: What would you say was the most challenging part for you in the making of the film?

ID: It was probably having way too much material. I feel like there was so much to be said and there were many, many things that I cut out of the film that were either, as it turns out, distracting from the narrative, or causing the film to be too long, or maybe just too “in the weeds” for regular people who were seeing the movie as opposed to people who were in the film business. I really hated losing that stuff, and it took me a long time to come around to certain things being expendable. I would say that that was the toughest part of it.

I had a moment early on where I was dealing with the issue of not really having the resources to do the film. I did a budget that seemed like a realistic budget for making a movie like this. When I looked at the final number, it was like, “I’m never going to be able to raise that kind of money.” Not for this film. So I made the decision to kind of go it alone, and do it really hand-to-mouth, as it were. I’m really glad I ended up doing it that way.

HtN: And you certainly travel a lot in the film, so there had to be a budget for that, which is expensive.

ID: Yeah. That was probably the biggest budget item other than the actual editing of the film.

HtN: Were there any people that you approached who, for whatever reason, did not want to be in the film?

ID: Yeah, there were some people who just felt like they had nothing to say that would have really helped the story. There were a few people who, I think, are still angry at Rugoff all these years later. (laughs) That was a very, very tiny group of people. Then there were a lot of older people who were just afraid to be on camera. They were worried about being incoherent or not remembering enough, or whatever.

It’s one of the reasons I made a decision very early on that I was not going to fuss too much with camera, and lighting, and composition and stuff like that, because I knew that some of these older people would get freaked out if I was doing too much of that, or if my crew was too big. So I kept it as simple and easy as possible, so that we could be in and out. When we did an interview, I would actually be on-camera interviewing them within 15 minutes of arriving; that’s how fast we were able to set up and get rolling. That was my way of getting around this fear that some of these older people had about going on camera.

HtN: That’s really interesting. Certainly, I’ve seen documentaries where, although I love the subject, I really wish the director had spent more time setting up an interesting shot. I did not find the compositions in your film distracting in the sense where I wished they were better. So, it works.

ID: I’m glad to hear that.

HtN: Having just watched the film via online screener, I noticed that you will need to update that dedication at the end because, sadly, Robert Downey Sr. has also passed. Do you plan to do that?

ID: Yeah, I’d like to do that. I just haven’t had a chance to. It’s a more complicated process than it sounds like. I could do it in two minutes and export a new version of the movie, but then I would have to actually convert it into a dozen different formats for all the different uses that it has. So that’s the only reason why I haven’t done it. But you’re right, it’s not just Robert Downey; Evangeline Peterson [Rugoff’s first wife] also died.

HtN: Oh, no!

ID: I actually want to dedicate the whole film to her, but I haven’t had a chance to do that, either. The list is getting longer. It actually vindicates my impulse, which was to try to get these people on camera as quickly as possible.

HtN: I noticed the many different camera people, by location in the credits, that you used in the making of this. I assume you just recruited local people to shoot wherever you were. What was that process like?

Producer/Director Ira Deutchman interviewing Lina Wertmuller for the documentary film “Searching for Mr. Rugoff”

ID: It was easy because every single one of them was a Columbia alum. They all know how to operate a camera, which is great. Peter Gilbert who, as you may know, was the cinematographer who shot Hoop Dreams and is a dear friend of mine ever since I worked on that film, acted in the capacity of what I would call supervising director of photography, or supervising cinematographer. I forget what title I gave him, but he guided me in terms of the camera equipment that I ended up buying, which is what I did; I didn’t rent the equipment, I bought it so I could have it with me everywhere I went. He taught me how to use it, how to get the best resolution out of it, and gave me tips about getting B-roll and all sorts of stuff like that.

Once he had done that, whenever I knew I was traveling someplace and we’d have interviews to do I would just put the word out to my email list of Columbia film alums, saying, “I’m going to be in Paris, blah-blah-blah, I could use somebody to sit behind the camera,” and always somebody popped up to volunteer. So that’s the reason why there are so many people whose names are under the camera category. I also honestly thought it was kind of amusing to list the camera operators that way, by location, because it’s a way of also communicating to the audience how many places I went.

HtN: Yeah, it’s like a nice reminder there at the end. So, I know that in the film you talk about how there’s nobody like Don Rugoff today, but is there anyone who in your mind approaches Rugoff’s mentality in the way they market films, or the way they present films? Not necessarily with those same kind of cool diorama displays, but something else like that?

ID: I think that when you look at some of the stuff that’s been done by A24, by Neon, a little bit by Magnolia, what you’re seeing is one side of what made Rugoff’s efforts so special, which is just being aggressive, just going for it, as opposed to a lot of smaller distributors these days that admit defeat before they even start. They basically spend so little money and so little effort because they have no confidence that the film is going to work. That’s not the way to get films into the marketplace. I think some of these newer companies – “newer,” they’re not that new – approach the level of confidence and aggression that I think was like what Rugoff used to do.

The part of it that I don’t see that much of is the cleverness, the uniqueness of an idea where it’s like, “What can we do to stand out? To be different from anything else that’s in the marketplace?” Rugoff really had a knack for that. It’s not just about how you look at the movie and try to find out what you can do to make it stand out. It goes even backwards into the acquisitions process, which is when Rugoff would look at a movie and he would always be thinking, “What’s the hook? What is it that we have here that’s different, distinctive, interesting, that can get an audience to pay attention?” I think that was his brilliance, and he was shameless about it. There was no idea too crazy to consider.

HtN: Yeah, and that definitely comes across in the film. So, a few times in the movie, you and others discuss the way Don Rugoff could be a difficult and demanding boss. Director Sarah Kernochan, at one point, even compares Rugoff to Harvey Weinstein, though not in the sense that he was a predator or an abuser. Still, it often seems, particularly before our present-day era, that one could expect certain kinds of less-than-ideal behavior in our industry than we would now, post-#MeToo. In what ways did Rugoff follow this model and in what ways did he not?

ID: Good question. One of the things that was on my mind when I was making the film was the apparent connection between very ambitious and creative people with a certain amount of arrogance and bullying behavior. Thus, the Steve Jobs quote at the beginning, which is a nod to the fact that this kind of behavior is not limited to the film business. But that was all before the Harvey stuff came out.

After the #MeToo moment, I was scrupulous in making sure that Rugoff’s behavior never crossed the line of being sexual harassment or violent in any way, and I was assured by everyone that it was never the case. As you know from seeing the film (spoiler alert), Rugoff had issues that, while not being an excuse for being so hard on his employees and everyone around him, are certainly part of the bigger picture. He was also very protective of his employees, seemingly aware of the abuses of others. In any case, that Weinstein comparison is in the film purposely to acknowledge the elephant in the room while making it clear that they are not equivalent.

HtN: Thank you so much. I really enjoyed the film.

ID: Thanks!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)