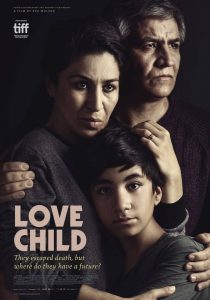

A Conversation with Eva Mulvad (LOVE CHILD)

I met with Danish director Eva Mulvad (The Good Life), on Monday, September 9, 2019, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss her new documentary Love Child (which I also reviewed). Over the course of six years, Mulvad and her crew follows an Iranian couple, Leila and Sahand, forced to flee their native country to avoid execution for adultery after having a child out of wedlock (while married to other people, in other words). Intimate and profound, the film offers a raw look at exile and the deep love that makes life worth living. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, I really like your film.

Eva Mulvad: Thank you.

HtN: How did you find your subjects?

EM: Well, one of the strengths of the film is that it’s shot over very many years, six, seven years, actually. And I came on board in 2013. That was one year after the action in the film starts off. It’s a couple who has escaped from Iran and they come out to Turkey, to Istanbul, in 2012 and, at this point, they have a little kid with them. He is turning five years old at that time. And they’re both married to other people, and this little kid has been raised in a family with a mother and her ex-husband thinking that that man was his father. But it turns out that they have had a secret love affair while being married to other people and that they cannot get divorced and now they want to flee for love, to make the family that they already have, even if they have never been able to live together. They had met in parks and restaurants and the little son calls his biological father “uncle” because he doesn’t know. So it’s a quite dramatic starting point, but I wasn’t on board when that happened.

EM: Well, one of the strengths of the film is that it’s shot over very many years, six, seven years, actually. And I came on board in 2013. That was one year after the action in the film starts off. It’s a couple who has escaped from Iran and they come out to Turkey, to Istanbul, in 2012 and, at this point, they have a little kid with them. He is turning five years old at that time. And they’re both married to other people, and this little kid has been raised in a family with a mother and her ex-husband thinking that that man was his father. But it turns out that they have had a secret love affair while being married to other people and that they cannot get divorced and now they want to flee for love, to make the family that they already have, even if they have never been able to live together. They had met in parks and restaurants and the little son calls his biological father “uncle” because he doesn’t know. So it’s a quite dramatic starting point, but I wasn’t on board when that happened.

The father has a little side story in the film with a political background. He was an English teacher in Iran who was being forced to work for the secret service in Iran, reporting on people, some of whom were activists from the Azeri minority, which he belongs to, but also because he speaks English. He also reported on foreigners. So sometimes he would just be hanging out in the bazaar just talking to people and one of the guys that he chatted up there was a Danish man who was there to make a film. And eight years later, when the couple decided that now they would escape, he called that guy and said, “I’m going to escape my country. I’m scared. I think it’s more secure for me if you would follow my story.” And that’s where the film starts.

So that guy is the co-director of the film and we’ve been shooting and having several teams working so that we could cover everything that’s happened. Some years we didn’t shoot much. Other years, when something starts to roll, we needed to go and be there. So it’s been a large team. But the starting point was actually that man contacting my colleague in Denmark.

HtN: What’s your colleague’s name?

EM: It’s Morten Ranmar.

HtN: And so your involvement, from start to finish with the film, was six years.

EM: Yes.

HtN: Even though the story predates that. So, how often during those six years would you or your team shoot?

EM: Well, it was very much up to what happened to the family. So, sometimes we had to be super alert because the plot of the film is that they are there applying for asylum in Turkey, and unluckily for them, it’s at the same time as a lot of refugees from Syria come out and then many other refugees as well, so it’s super difficult to get an answer from the UNHCR [The UN Refugee Agency], and we are waiting.

The plot of the film is actually them waiting for that destiny to be determined by the system that we are part of. So some years, especially 2014, I was there like maybe five, six times during the year and other years it was one or two times. It was very, very organic. I think one of the strengths for me in this film is that what happens is not happening for my camera, it’s happening because it’s happening in reality and I think you can feel that strength, that organic feeling of the film that the events are not created for the sake of the film, but that the film builds on events happening in reality and that gives excitement.

HtN: Absolutely. One of the things that’s really remarkable about your film is the intimacy of your access, the fact that you are embedded with a family going through some pretty difficult situations. The camera’s there, but it’s not obtrusive, and they don’t address the filmmakers at any time. How hard was it to get to that level of intimacy, regardless of who was shooting?

EM: I mean, people are different. Subjects in documentary films are as varied as we are. And with this particular family, one of the qualities that I could see very early on was that they had no difficulty showing their emotions. They were very transparent, and they were very trusting, and it was very easy for us to be accepted in their families. So, I have shot many documentaries, and this is one of the cases where it has been the easiest access to emotions, intimacy. And I think that’s very beautiful, and that’s very strong for an audience to be invited into some really clever people in a difficult situation trying to handle pretty severe problems, and doing it in a very human way. I’m very grateful that they accepted us that way and it was not a hard relationship to build with them.

Filmmaker Eva Mulvad and HtN’s Chris Reed

HtN: How about with the other, more peripheral, characters, like in the home where they live, in Turkey, with the neighbors and then in their workplace, particularly the school, where you have other children? How hard was that, if at all, to negotiate?

EM: It wasn’t that difficult. I mean we came in and out for many years, so we were kind of part of their life, so the neighbors got to know us and at the school they didn’t have any problem. We also created a little video for the school that they could use on their website. So, you know, as with everything in life, it’s a give and take and if you give, you can take.

HtN: Were there any moments in the six years that you were involved in the project where there were things that happened that perhaps you later wanted to include in the film but didn’t for whatever reason, or things that you were unable to capture that you would have liked to capture?

EM: Yes. I think we didn’t know exactly what film we were shooting, at first. We didn’t know which storylines would grow and be strong. So, for example, there were many, many aspects of the first establishment of oneself in a foreign culture that I would have liked to be able to grasp better, because, in the shooting of the early parts of the story, we kind of jumped out of it too fast, and were missing some of that.

HtN: Speaking of cultural acclimation, what was your experience in this region, either as a visitor or as a documentarian. How much were you also learning the cultural ropes when you first started making this film? Had you traveled a lot to Turkey before?

EM: Just with this film. It became many years with this film, and I saw the changes there, with Erdogan…

HtN: Their very own right-wing populist…

EM: He has definitely set a whole new standard for democracy, which is maybe quite a low one, I would say. Their life right now is getting more and more difficult because of his politics. And when in the beginning I came there, it was a prosperous place. There were a lot of buildings going, like a lot of work, and now they took a lot of refugees in and the politics is more and more strict and foreign companies are getting out of there. So, everyday life is getting hard there. And of course, for the refugees, the low end of society, it’s not easy.

HtN: But the family now has something more than just refugee status in Turkey, don’t they? How are they doing now? You end the film on a very hopeful note: no, they have not left, they’re not in America, but they’re building a life for themselves in Turkey, they seem happy and their son seems happy. What is their official status within Turkey now?

EM: They are all recognized as refugees under the UN, which means that they cannot be sent back to Iran, which is … that’s the most important. But the problem is that they are not “eligible for resettlement,” which is like a phrase that you use in the UN system. A resettlement means that somebody else, a country other than Turkey, takes them in and allows them to build a life and maybe, in the end, grants them citizenship, and that’s not the case for them. And because they have been so good at integrating in Turkey and actually have jobs, many other people will come first in line, more vulnerable people, so they can face this kind of … it’s kind of a stateless situation.

They don’t have the basic rights that I have. They cannot take anything to court if they wanted to. If they don’t have a job, if the job does not pay them, they have nothing. So they’re very vulnerable. But I don’t know if they would be happier coming to America, for example. You have to start all over again. Not being able to get themselves into the status of the job situation they have now. It’s the same status they had when they left Iran. I guess it’s never easy to get it all. And in Turkey they live quite happily. They are very well integrated in the community and they have a job, but they don’t have basic rights.

HtN: Would they ever be eligible to become Turkish citizens, since they are employed and integrated?

EM: It’s super difficult but they are trying. They have working permission in Turkey now, but there are so many refugees … I mean I’m very critical towards the political side of what is happening in Turkey, but I must say I was also super impressed by the people, normal people, so friendly and so open and so warm to this family. I know there have been a lot of problems, as well, but this family was super well received and with a very open warmness from the Turkish people.

HtN: So, final question: how long did it take you to come up with the title of the film, Love Child?

EM: It took quite a long time. I think we had five other titles before it, and I had dismissed it many times as being too saucy, too kind of American. (laughs) But in the end, we had to acknowledge that that might be the best title for this story.

HtN: Is it a title that you’re keeping in English in other languages, or is it being translated?

EM: We don’t have the same thing, exactly, in my language, we don’t have the exact meaning that you have. We can call it “kærlighedsbarn,” which means love child. But you have in English, a “love child” is a child made outside of a marriage, right?

HtN: Right.

EM: And in our language, it is a child made out of love.

HtN: Right. So it has that extra connotation. Well, I really enjoyed the film. Congratulations on making it and I wish you all good things with it.

EM: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?