A Conversation with Elizabeth Lennard (TOKYO MELODY)

Music-related documentaries of the biographical variety are generally a mixed-bag. Show a songwriter in the midst of their craft and add a few talking-head sequences with others expounding on their evident greatness and you have yourself a nonfiction film with a built-in audience, in theory. Admittedly, while most are “standard issue” or worse, an exceptional work of insight slips through on occasion. Such is the case with Tokyo Melody, the debut feature-length from filmmaker / photographer Elizabeth Lennard (getting an apt one-off revival at JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film in New York at the end of July). The French / Japanese television co-production chronicles the recording of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s solo-album Ongaku Zukan [Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia] with fascinating interludes featuring Yellow Magic Orchestra, diversions at home with Akiko Yano and on the streets (and subways) of Tokyo interspersed with snapshots of life both incidental and consequential.

Transcending the conventional trappings of artistic profiles, Tokyo Melody is a fascinating journey into the sights and sounds of mid-1980s Japan through the eyes of two multi-talented individuals: the subject and the filmmaker. Anyone with even a casual interest in Sakamoto would benefit greatly from this exceptional portrait of an artist in a period of personal and professional transformation.

Elizabeth Lennard: I heard that you had just returned from Europe?

Hammer to Nail: Strangely enough, I was in Paris about a week-and-a-day ago. I wish that we could’ve spoken in-person.

EL: That would’ve been great. I’m sorry that didn’t happen.

HTN: You’ve just returned as well.

EL: I had an opening at the Arles photo festival [Recontres d’Arles] and I just came back from there. You’re working today [on 4-July]?

HTN: I work every day. I believe that you’ve spent some time in the Bay Area?

EL: I grew up partially in Berkeley. I was bicoastal. I grew up in New York and Berkeley. But I went to Berkeley High [School].

HTN: I have wanted to write about Tokyo Melody for quite some time. Until recently, I’d only ever read about the film. I knew of its existence but I hadn’t had the opportunity to see it. You’d made earlier biographical films but in what capacity were you positioned to make a film about Ryuichi Sakamoto?

EL: I really was quite young. I had made two short films in France. One was a documentary on pianists called the Labèque Sisters [Duo with Katia and Marielle Labèque (1984)]; the other, Meeting with Gisele Freund (1981)]. I was at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983 when they were showing Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. I was blown away by the film, discovering Sakamoto, the actor / musician / composer. When I came out of the screening, I actually ran into two French producers I knew who worked at the experimental part of French television, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel [INA]. It wasn’t a channel. Their job—they still exist—is more the French TV archives. I have no idea if there is an equivalent in the U.S.

HTN: Unfortunately, none that I am aware.

EL: One of the producers, Muriel Rosé, knew me because of my very first short film [Mardi Gras (1979), based on a poem by Blaise Cendrars]. They said to me, “If you have any way of getting in-touch with Sakamoto, we might have the budget to produce a documentary on him.” That didn’t go to a deaf ear but I had no way of getting in-touch with him. This is pre-internet, pre-everything. At that time, as a photographer, I was living part of the time in New York. When I returned to New York, I went to a restaurant called the Odeon. Have you ever heard of the Odeon?

HTN: I have been there, coincidentally enough.

EL: Before living in New York again, I lived in Los Angeles. While I was going to UCLA film school, I began to do album covers for A&M Records. They would give me records sometimes because they had many records they’d issued. Although it was a Japanese record, they released YMO in the United States. In fact, I had YMO’s records in my apartment in Paris. I hadn’t really made the connection but at the next table [at the Odeon], there was a big table full of people. There was a man who I knew who had worked at A&M and later became the Vice President of Virgin: Jeff Ayeroff. I asked, “Do you have any way of connecting me to Sakamoto?” He said, “You’re in the right place!” Because at the table there was somebody named Kiki Miyake who had been their tour manager when YMO did a U.S. tour in the late-1970s. Kiki actually now lives in Los Angeles. Kiki Miyake was able to connect me to Sakamoto and he was going to Berlin to record. He had done the music for Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence but he was doing an album with David Sylvian and recording it in Berlin. I think he was recording a version of “Forbidden Colors” as a single. It hadn’t been released as a record yet. In Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, you hear the melody of “Forbidden Colors” in the film.

HTN: You’re quite right. He recorded a version with David Sylvian. I believe it was released after the movie had come out (although it appears on the soundtrack LP). You seem to be quite right about the timing. That appears to be the chronology.

EL: Somehow Kiki was able to set up a meeting for me in Berlin, at the recording studio next to the Berlin Wall, to meet Sakamoto while he was recording with David Sylvian. I arrived in Berlin and I showed him a book of my photographs [Painted New York]—painted photographs of New York—and he apparently liked them. That is how it happened. That is how he agreed. He was already a star in Japan but not in the U.S.. Even though YMO had done a U.S. tour, I don’t think that he was very well known in the U.S. at the time.

HTN: The awareness of Yellow Magic Orchestra and his solo albums were still fairly limited in the U.S. at that time. In Japan, of course, it was quite the opposite. There are a pair of scenes where he stands outdoors in the frame and, in the background, there is large video screen behind him. On the screen appears an excerpt from a YMO concert and evidently a commercial in which he appears. How did those sequences come about? The framing and the way that you set-up those pieces are rather fascinating.

EL: This is low budget cinema. A documentary from the experimental part of French television. We had a small budget but nothing like a budget of a major film, At the time, anything like special effects was not something we were thinking of doing. Instead, we rented the screen. With our little budget, we were able to rent that screen for 45 minutes and we prepared a loop of a few of these videos. One, you’re absolutely right, is an advertisement for a famous Japanese insurance company where Sakamoto is drinking sake or something. The other is a video for YMO. We had a few different tapes and my line producer went upstairs there [to start the loop]. Sakamoto was already a big star in Japan and they were afraid of crowds. He was already only in his limousine and not walking around or anything like that. He never could walk around. Instead, we did that shot very early in the morning. Seven in the morning where there were not very many people. The thing that struck me was that he stood there—where you see him in the frame—but after a few minutes, there were a few groupies who came and sat down on the sidewalk and started to cry with emotion.

HTN: Really? Even at that hour.

EL: Of course they recognized him. That was how we did that shot. Even the shot, for example, in the subway was staged. First of all, he would never take the subway at the time. We said, “We’re going to take you in the subway from one station to the next.” It was all improvised but there happened to be an ad in the background of the subway car. That was kind of lucky.

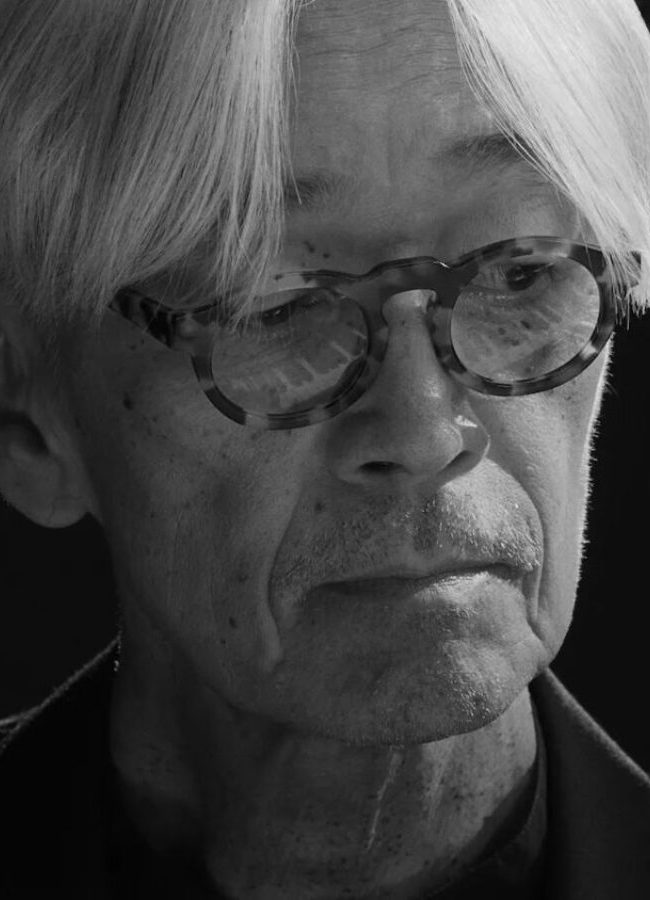

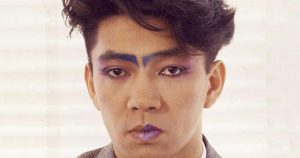

A still from TOKYO MELODY

HTN: There is another scene late in the documentary where you have Akiko Yano and Ryuichi Sakamoto playing together a song that YMO recorded (which Sakamoto wrote), “Tong Poo” [“East Wind”]. Were they fairly open to performing on the piano for you? Obviously, she had toured with the band as a keyboardist for several years and she had released several albums by that point and many in the years since.

EL: I only found out recently that is the only time anyone ever filmed them playing together at home.

HTN: That is what I’d imagined. It is truly amazing footage.

EL: I don’t know how much you know about Japanese culture but I was told that, in Japan, the woman is in charge of the home. I had asked Ryuichi to film in their home and he said that he would ask her. He asked Akiko and she said yes. We were there to film him and she agreed to play with him. Completely unplanned.

HTN: It seems as if there are many moments in the making of the film that were immensely fortuitous. There exists other material much later in his life of him recording in the studio but very little from earlier in his career. You allow for an astonishing grasp of his creative process in the making of Ongaku Zukan [Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia] . You get a firm idea of what his compositional practice was like which you do not see in many other films.

EL: Obviously, we were very lucky and there was a good atmosphere. The whole thing went very well. What can I say? You know, it is not always the case. For me, Ryuichi was a true artist. He is really a composer, as you know. When I met him, he was sort of transforming back to being a composer, in a sense. YMO was big. They were like the Beatles of Japan. It was completely inventive.

HTN: How did you select your team? I believe that the editing in the film is fairly spectacular. Spending time in a recording studio is not exactly the most exciting period to witness. Capturing that and making it interesting is a challenge for any filmmaker.

EL: I was very lucky because I was able to work with Makiko Suzuki, a Japanese editor based in France. This is French national television and usually you have to use someone already available. Sometimes you get better people than other people but I was very fortunate. My producer there, Muriel Rosé, really looked after me. They chose a very good soundperson, Jean-Claude Brisson. We actually filmed the film in 16mm stereo which was a very short-lived format. Sadly, Makiko Suzuki passed away very young from cancer. She really was very helpful, obviously, and she knew who Sakamoto was and she was really excited by the film. [For the sound-edit] we had the film-print on one thing and magnetic sound on the other.

HTN: The stereo-print evidently had a mag-track (since the output of an optical track would be mono, otherwise)?

EL: Exactly. These are problems that people do not have at all anymore. The camera got out-of-sync. In other words, when you sync-up a film, you get the little tiny numbers on the film and the magnetic tape, which helped you. It wasn’t just the clapboard. It wasn’t just that but there was a way for you to keep the film in-sync. Somehow all of that disappeared when we were filming during the festival with sum0 wrestlers and the orchestra. It is this festival that they have every year. The sumo wrestlers were carrying the shrine but they decided that my cameraman should attempt to carry it and then they would film. They took the camera from him and then they put him under the shrine. There was nothing he could do. They were these big guys and he went along with it! Somehow, that made the camera go completely out-of-sync. When you see the procession and there are different musicians playing asynchronous music, I just remember my poor editor having to re-sync that music. It took her hours! It was a nightmare.

HTN: Re-syncing the out-of-sync asynchronous audio.

EL: It was challenging for her. I guess you noticed the Fairlight?

HTN: The synthesizer. Absolutely!

EL: At that time, the Fairlight was the latest machine.

HTN: The moment when he is displaying the enormous floppy discs to access all of the sounds for that system is rather charming. It is a true time capsule of what was, at that moment, cutting-edge.

EL: People who loved the Fairlight have taken that sequence and put it on YouTube. At that time, it was completely new. I think it cost $50,000. [In 1980, the price was approaching $30K; price-adjusted, roughly $80K now.] It was very expensive! I know that now you can do the same thing in your phone or whatever.

HTN: Not quite. But nearly! What would you note is the intersection between your photographic work and your film work? The process is somewhat different, naturally, but there are similarities.

EL: I have always been someone who liked to photograph cities.

HTN: Specifically architecture?

EL: Yes, but make it very personal. I had a show at the Pompidou Center in 1979 of PAINTED NEW YORK. These are hand-painted black-and-white photographs of New York. It was my way of looking at New York. Looking at Tokyo, there were days when Ryuichi wasn’t with us but we did ask him, “Where should I go?” One place he suggested, which you might remember, is something that they called the “suicide apartments” in Tokyo. People would go there to jump off the roof [of the Takashimadaira complex]. You remember the sequence where it looks tinted blue at the apartment building? The film is a portrait of Sakamoto but it is also a portrait of the sounds of Tokyo. You can hear the ticket-takers in the subway and the Pachinko machines. There is a lot of that.

A still from TOKYO MELODY

HTN: You also incorporate aspects of Japanese street culture, such as some of the 1950s impersonators which can be seen in Chris Marker’s SANS SOLEIL [SUNLESS] as well.

EL: They would dance and it was wild. We just went there and filmed there. I hadn’t realized that Chris Marker filmed at the park but it is interesting that you point that out. When I finished TOKYO MELODY, there were some festivals that showed it with SANS SOLEIL and even with Wim Wenders film [TOKYO GA].

HTN: That certainly makes sense. For the JAPAN CUTS screening, I believe you will be in-attendance?

EL: I will be able to attend. This is like a pre-release because we are trying to sort-out contractual details to be able to release it in movie theaters in Japan and, hopefully, in the U.S. It was never released theatrically at the time. It was only shown on television here and then in film festivals. That is partially why they’ll be showing the 16mm print in New York rather than a DCP.

HTN: I am certain that they’re delighted to be screening the imported 16mm print. I suspect that the audience will be grateful for the opportunity to see it in whichever way possible!

[The JAPAN CUTS screening will be introduced by Akiko Yano and will be followed by a Q&A with Elizabeth Lennard.]

TOKYO MELODY (1985)

dir. Elizabeth Lennard [62min.] Institut National de l’Audiovisuel [INA] / Yoroshita Music

– Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)

Cover photo credit courtesy of Elizabeth Lennard