A Conversation with Camille Thoman (NEVER HERE)

“I want to entertain and titillate, but also ask questions of the viewer“– Camille Thoman on Never Here

“I want to entertain and titillate, but also ask questions of the viewer“– Camille Thoman on Never Here

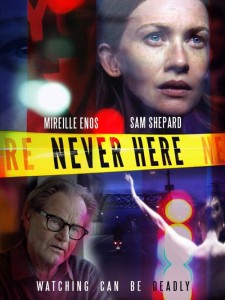

Premiering at this year’s LA Film Festival, Never Here marks the narrative debut of writer-director (and performance artist and editor and doc-maker) Camille Thoman. It also marks the last screen performance of the late Sam Shepard, who is unsurprisingly riveting alongside Mireille Enos (The Killing) in the starring role of Miranda Fall, an installation artist whose art dealer and secret lover Paul Stark (Shepard) witnesses a violent assault from her apartment window. Which leads to Miranda giving Stark’s account to the police – while lying about being the primary witness – in order to simultaneously nab the perpetrator while keeping her lover’s identity concealed. Thus begins a detective story, that turns into a psychological thriller, that soon becomes a mood-induced meditation on voyeurism, identity, morality – and ultimately reality itself.

I spoke with Never Here’s unconventional director prior to the film’s Oct. 20th theatrical release.

Hammer to Nail: Your narrative debut stars The Killing’s Mireille Enos and the late great Sam Shepard in his final screen role (alongside terrific character actors like Goran Visnjic and Vincent Piazza). Zachary Quinto is also listed as exec producer. So how exactly did you land all this “name” talent? Do you have any advice for first- time directors looking to do so?

Camille Thoman: Baby steps. One thing leads to another. I was very lucky to convince Mireille Enos to star in my short film Falling Objects in 2006. She and I became friends, and then I wrote the part of Miranda for her, though for years it looked like she would not be able to play it. I lucked out with that one! Mireille is my favorite actress in the world. Zach Quinto signed on as a producer after he took a meeting with EP Greg Ainsworth and me. We couldn’t believe our good fortune. It was astonishing to me, and still is!

It helped that Zach and his producing partner Neal Dodson liked my short film, and my documentary, and were also friends with Mireille. So again, everything builds on everything else. Sam Shepard came to the film quite late, and again, we couldn’t believe our good fortune and the huge gift that presented itself to us. I would say to first time filmmakers that when you really believe in your vision, it magnetizes people to the project. And when you work really, really hard, and have a lot of doors slam in your face, some doors open. And then you walk through. Hard work, confidence, patience and good team play are key.

HtN: I actually first met you back when The Longest Game – your heartwarming portrait of four elderly, paddle tennis-playing Vermonters – screened at the Gasparilla International Film Festival, where I was on the doc jury that year. To say that Never Here is unlike that film is certainly an understatement. Which makes me wonder what it was like for you to transition from nonfiction to narrative work. What were the similarities, and also the different challenges?

Sarah Linden (Mireille Enos) – The Killing _ Season 3, Episode 3 – Photo Credit: Carole Segal/AMC

CT: I love hearing you say that! I see them as similar in many ways. They are tonally different explorations of the same theme: metamorphosis. The construct of our belief that things are fixed. I tend to explore a version of the world as in a constant state of flux. What appears to be fixed – foremost identity – is not as static as we would like to believe. In Never Here this is probed through the lens of a thriller. Loss of identity can be terrifying. In The Longest Game the redemptive nature of change and regeneration is explored,

Whether I am working in narrative or doc I always have a sense going into the project of what the film will be. With both the doc The Longest Game and with Never Here I used this sense as a guiding light. It’s as if the film, in whatever genre, talks to me as I am making it, telling me what is right and not right. On the other hand, in both mediums, there is the inalterable necessity of finding things in the moment. With a documentary finding things in the moment is a more patent part of the process because you don’t know what anyone is going to say or do. But also with Never Here we were discovering and unearthing in the moment all the time. I was working with a kickass DP (Seb Wintero). He encouraged us both to abandon any plan we had if something better occurred to us – which happened constantly. But I could see much of the film in my head before we shot, and I was careful to respect the integrity of those images, and do my best to bring them into physical reality.

HtN: Since you’re a New Yorker turned Angeleno I’m also curious to hear what you think are the pros and cons of both coasts career-wise. Do you feel it’s easier to make indie films in LA these days?

CT: Hmm, interesting question. I love NYC. It’s my hometown, where I was born and raised. It’s in my blood. But I left it because I felt too much pressure to make money – and look good in NYC! I didn’t have the creative space I was looking for. In LA, I walk my dog in my pajamas in the morning. No one cares. People give each other a lot of space. Creatively for me, that’s fuel. So at the moment, yeah, it’s easier for me to live in LA and be a filmmaker. But I travel to NYC every six weeks or so because I never want to live without her!

HtN: Could you elaborate a bit on the film’s unique sound design, including James Lavino’s score? (Which one reviewer referred to as Lynchian.)

CT: Yes, our fabulous sound design came from two sources— firstly, the remarkable talent that is James Lavino. James came on very early to the project and scored the film as I was editing. This was an amazing luxury. He and I tried out many, many different sounds, and he wrote gorgeous pieces that didn’t end up being used because the scene was cut (the painful downside to working in this way). However, as a result, we found a sound that really served the film beautifully, note by note.

The second part of the sound equation was finding a singer/songwriter called Elijah Ray. He watched the film, with the pieces that James had written, and created an ambient choral sound which catapults the soundscape into unworldly territory. He recorded himself singing, whispering, making generally amazing sound with his mouth. I used these sounds throughout the film, and James would then incorporate Elijah’s music into stuff he was writing as well. It was patchwork, and at the same time organic. I’m very happy with how it turned out. I have these two remarkable musicians to thank for that. Elijah does concerts all over the place, and I highly recommend going to them. They are gorgeous dance fests!

HtN: Finally, can you let us in on the film’s influences? I saw Hitchcock and Polanski, obviously, but since you’re also a performance artist I’m thinking there may have been some non-cinematic artistic influences that I didn’t pick up on as well.

CT: I’ll take Hitchcock and Polanski! I’m a huge Polanski fan (which doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be in jail, by the way). Though Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now with Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie was probably my primary cinematic inspiration.

I would say my biggest influence was the work of novelist Paul Auster. Primarily The New York Trilogy, but other works as well. When I first read the trilogy at the age of 20 or so I felt like the novelist had reached from the pages of the novel and squeezed my heart. He was able to create detective fiction – intrigue and enthralling suspense – and then connect out from the pages of the book in 3D. and reference me sitting there reading it. It was a shocking moment, to be funneled into a “detective fiction” setup, and then realize that the author is talking about much more than just his plot. I thought, this is something I want to do in cinema. I want to entertain and titillate, but also ask questions of the viewer, and not just allow them to be subsumed in the narrative.

– Lauren Wissot