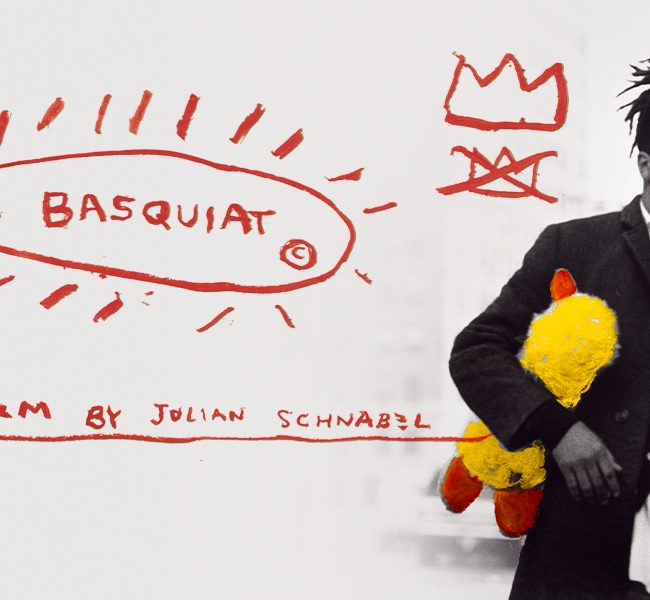

A CONVERSATION WITH ARIE & CHUKO ESIRI (EYIMOFE/THIS IS MY DESIRE)

Eyimofe (This Is My Desire), the debut feature by the Nigerian twin brothers Arie and Chuko Esiri, premiered at the 2020 Berlin International Film Festival in February 2020, mere weeks before the world shut down. Just over two years later — following a mostly virtual festival run, and U.S. theatrical bookings in 2021 — the film is joining the Criterion Collection, with a DVD and Blu-ray release scheduled for April 26. That’s a remarkable accomplishment for two first-time directors a few years out of graduate school, but Eyimofe is a remarkable film.

The movie is divided into two sections, each telling the story of a protagonist who seeks to leave Nigeria for better opportunities in Europe. In “Spain,” a middle-aged engineer named Mofe (Jude Akuwudike) is scraping together money for a passport and visa when family tragedy intervenes. In “Italy,” a young hairdresser and bartender named Rosa (Temi Ami-Williams) hopes to emigrate with her pregnant younger sister, if she can navigate through a maze of would-be suitors and sinister fixers. Both Mofe and Rosa find their way blocked: by bad luck, by bureaucratic inefficiency and government corruption, by the greed and duplicity of friends, relatives, and strangers. If the shape of the stories points toward a kind of pessimistic determinism, the film is lightened by glimpses of warmth and generosity, and both strands of the narrative are powered by the bonds of familial love.

Eyimofe is an intimate epic: it burrows deep within its characters’ inner lives, while attaining the sprawl and reach of a 19th-century social novel. (Chuko Esiri, who wrote the screenplay, has cited Dickens’ Bleak House and Joyce’s Dubliners as influences.) As Mofe and Rosa circulate on their separate journeys, we meet doctors and nurses, casket salesmen, expat businessmen, black-market hustlers, and more. The film’s wide frames and long takes make Lagos, the largest city in Africa, feel like a major character in its own right — a place humming with color, community, and vitality as well as danger and desperation. A worthy successor to the tradition of humane, socially engaged cinema, Eyimofe is a movie that deserves to be seen and talked about for years to come.

I spoke with the Esiri brothers on Zoom recently. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: You were born in Nigeria, you went to school in England, and then you both ended up in MFA programs in New York at the same time, Chuko at NYU, and Arie at Columbia. Can you talk about when and where the desire to become filmmakers first developed? Did one of you get there first?

Chuko Esiri: We found our way here simultaneously, but through very different routes. Arie was on track towards becoming a cinematographer, he felt that’s what he wanted to do. And I was coming up through being a producer, which is what I thought I wanted to do. I think the desire was cemented when we were both in college, but again, we were seeing it happen simultaneously, because I was at university in the north of England, he was at university in the south of England. But watching films and storytelling and performing, even if it’s only for ourselves, has always been a feature of our lives. I think some of it has to do with growing up in a house with frustrated artists for parents. Our mother is a lawyer, but she wanted to write, and our father’s an entrepreneur, but he wanted to paint. Some of that bleeds into you. When you’re young, you watch these adults tell you to go get a job and be responsible. And I guess a piece of you recognizes that they’re not completely happy in said jobs. So I think some of it lies there. But we came here at the same time on different paths.

Arie Esiri: I like to think I got there first, personally, but you know… (laughs)

HtN: Can you talk about the genesis of the story, and at what point you realized that this would become your first feature film?

CE: The node of the idea came when I moved back to Nigeria a couple of years after college. I was there doing my National Youth Service. Arie had done his the year prior, and I came afterwards. [Before then,] we were only engaging with the country in a superficial way. Even though we went back every holiday and our parents’ lives and businesses and networks were all here, and our friends, and all of that — you come back from school, you’re here for no longer than eight weeks, which is the long summer holiday, you’re not there to try to make a living. It’s all fun times. That’s what holidays are. The emotional responsibility doesn’t exist really when you’re a teenager, you’re not paying attention to the larger things around you. The state of the place doesn’t weigh as much upon you because you’re not paying for gas and you’re not making a meager salary and you’re not stuck with having to apply for your passport and your visas or all these things that your parents are taking care of.

So you’re not engaging with the place in a substantive manner. And this was the first time that was happening — one was dealing with all of it and it was very, very uncomfortable. And my immediate desire was to go back to what was familiar and comfortable and efficient and less arduous. That was where the kernel of the story came. [The treatment] was part of my application for NYU. And it evolved over time, as the migrant crisis became a thing. Mainly it evolved as my time in Nigeria extended and I began to — I don’t know if I fell in love with my captor, the Stockholm Syndrome, or if it’s just adaptation, but I grew to really love the place, and it became a wellspring of massive inspiration, and purpose, and drive. So as that was happening, the story changed and evolved, but at its heart, this idea of wanting to leave and wanting to be somewhere better can be traced back to that experience.

The Criterion cover for EYIMOFE (THIS IS MY DESIRE)

With regards to it being our first feature, I think it was more a form of function. It was more pragmatic than any planning. The script was my thesis for my MFA as a screenwriting major, and once you start working on something you just see it through. We got very fortunate with our funding as well. And everything cascaded quite quickly after that.

HtN: Speaking of the migration issue, I’ve heard you describe the film as a story of reverse migration, where it’s not so much about the journey abroad, but about the circumstances that would make one want to leave home in the first place.

CE: Our feeling was, in that period during writing and before shooting — I mean, the migrant crisis is still a massive problem, it’s just been superseded by a different crisis. But what we were seeing a lot of was, it was always stories from the other end. Or it was stories about the perilous journey. Everything was drawn towards the extreme side of this issue. And when you watch the news, it’s people in life vests in the Mediterranean, or cramped in detention camps. And these individuals have no humanity. You have no sense of what they’re coming from, or what they’re going to, or what they desire.

And I think for us, it was important to actually put lives behind these people, so that you recognize that it’s just individuals seeking the same thing every single person wants, which is the opportunity to flourish, or the opportunity to provide for their loved ones and to allow them to flourish. And part of it is also to recognize some of the courage and the sacrifice that’s made. I think people neglect that it means leaving your network behind, it means leaving the familiar behind, even as broken as it is. Our characters have support systems of sorts, in their families and friends and in their communities. You’re leaving all of that behind, and that’s not a decision that one comes to lightly. For every ten people that want to leave, more than half of them are afraid of actually taking that step because of what it means. So that was really it for us. A film has many ambitions, but that was the thing we tried to keep at the center of our minds: that we’re telling a story about people, and family, and the things that they want.

HtN: Chuko, you mentioned earlier that you worked in the industry with the intention of becoming a producer originally. And Arie, you were working in the camera department. I’m curious to know what effect those different backgrounds had on the way that your relationship as co-directors developed? And how did that relationship work out day to day, on the set, in the editing room, and so on?

AE: What I usually say is that if you stumbled on set on any given day, you’d find me with the camera department, with the cinematographer, and you’d find Chuko with the actors. And I’d be with our on-set editor as well. The visual architecture of the film, that responsibility fell mainly on my shoulders, I’d say. There’s also a certain proximity that Chuko had to the story, just as the writer. I was involved in all 13 or so drafts that he wrote, I gave a lot of notes. I guess one of the things where my hand is seen most visibly in the film is aging up Mofe. Mofe was originally a man in his thirties. And I came up with this idea that aging him up would open up the story in different ways, and make the casting more interesting. I had already seen Jude Akuwudike, who plays Mofe, in several plays in the UK. He’s an actor I’d always wanted to work with, so that gave us the opportunity to have him involved in the project. But I think it also just changed the shape of [the story] drastically.

In pre-production, I would spend a lot of time shot listing, thinking about different ways to block various scenes with the locations that we had already found. Chuko would run rehearsals with the actors and develop backstories, and take Jude, for example, to some of the places that Mofe visits in the film, some of the real-life locations and our local restaurants, watch soccer games with him in the marketplace. And then we’d convene at the end of the day and share notes. I would show him what I was working on with the shot list, he would show me some tape from rehearsals. So when we went onto set, we had a common language. We knew what we were going for with the performances, and we knew roughly the rules of the film.

And then in the edit, we had the great fortune of having Andrew Stephen Lee, a wonderful editor, and a wonderful director in his own right, as a mediator. Probably that was the hardest part of the process, editing — I think the film changes so much in that space of time, and because there were three of us, we could take things to a vote.

CE: We very much operated like a Supreme Court where Stephen was always the swing vote. (laughs)

HtN: The visual architecture of the film is very distinctive. You film the actors in a lot of medium-wide and wide shots, with a lot of long takes. And that allows the viewer to really see and feel the city of Lagos as a vivid presence in every scene, almost every frame. How did that visual style develop?

AE: I guess it starts with our reference films. We were looking a lot at New Taiwanese cinema, Edward Yang in particular. It’s a movie which has a lot more close-ups than ours, but I’d say Taipei Story was pretty influential in making this. We had also considered The Apu Trilogy, we watched all those together. Mandabi was an important film for me in developing this as well — that also has way more close-ups than we do.

CE: The Big City as well was a reference film of ours, Satyajit Ray.

AE: Right. Yeah. And including Lagos as part of this story was always going to be important for us. Chuko had written a lot of locations into the script. And I was always hesitant about tackling Lagos in that way — you know, moving from place to place, on any given day, even on a Sunday, is very challenging as an individual, talk less of a crew of 70 people and equipment and trucks. So I did try to cut down the number of locations on a number of occasions, but I just found it took away so much from the script. And we just sort of caved to the idea of trying to make it work. I don’t think I’ve said this in an interview before, but part of it is also just thinking, how do we manage the size of the script, the ambition of it location-wise, to feel like we are capturing Lagos, but also to carve out these intimate moments between the characters in some of these very congested spaces? These are all the things that we were considering as we were developing the language of the film.

A still from EYIMOFE (THIS IS MY DESIRE)

And our AD, Monica Palmieri, was really wonderful. She did a great job managing the amount of traffic but still allowing life to go on as our cameras rolled. I think a lot of it had to do with the relationships we built in these locations. Chuko had spent over a year visiting Mushin, which is the district that both Mofe and Rosa live in. He was not a stranger to anyone there. That allowed us a certain amount of access to shoot the way we wanted to. Some of those complicated night scenes — there’s a scene where Grace meets Mofe at his workstation, and to light that kind of space at night is something that’s very difficult to do in Lagos, but we were able to do it because of the relationships we had. So a lot of different factors played into how we were able to shoot the film in Lagos, but preparation is a really big part of it. It starts from watching the movies, and then it goes on to building the relationships with the people in the places that you want to shoot. And having them trust you to stay up to 2am at night with huge lights shining into some of their windows.

I think there’s also this thing that you’ll hear from other social realist filmmakers, whether it’s [Ken] Loach, or some of the New Taiwanese folks, like Hou Hsiao-hsien: you don’t experience life in cuts. That was the idea of doing the long takes — allowing people to live in a scene for a bit. There had to be a very good reason to cut to a different angle to see something else. A big part of it as well was, we know that people don’t see Lagos often on camera. That’s something we wanted to achieve — to allow the exoticism of the place to wear off. To allow you to sit in those long takes, particularly at the beginning, and familiarize yourself with the location and become a part of the fabric of the film as an audience member.

HtN: In some ways, you could argue it’s a pessimistic film. It’s a story about dashed hopes and dreams, a story that really plunges into social dysfunction and political dysfunction. At the same time, Teju Cole argues, I think persuasively, in The New Yorker that it’s fundamentally a film about goodness and kindness. And the epilogue, without giving anything away to readers who haven’t seen it, hints at forgiveness and reconciliation. Can you talk about finding that emotional balance, between optimism versus pessimism, light versus darkness?

CE: I think that balance of pessimism and optimism is a typically Nigerian thing. There’s a very famous saying here, that no condition is permanent. In general, we always believe in a better tomorrow. And it filters into us as people and as filmmakers. There’s a huge amount of dysfunction and so much that is wrong. But the people — I always say, love Nigerians, hate Nigeria. The people are truly, truly, to me anyway, exceptional. And bold. And strong. And we just want an opportunity to meet our potential. I mean, the stories you’ll hear — you’ll hear about somebody that has $100 in their account, and [someone else] needs fees for school or whatever, and they’ll give them 80. And they’ll have 20 left, “but I’ll manage.” At its heart, it’s a very communal place with a communal spirit. It’s just with the history and the imposition of a different culture, that has sort of been eroded, but it’s difficult to get rid of the hardwiring. And yeah, it’s hard here, I mean, things are a complete mess. But I can’t envision myself anywhere else. And I still believe in the place, in the people, and in that better tomorrow.

HtN: Fantastic. Well, congratulations on the success of the film, and congratulations on becoming part of the Criterion Collection — every filmmaker’s dream, right?

AE: Absolutely. That’s how we watched a lot of the films we talked about as references — people would bring back Criterion DVDs of The Apu Trilogy and The Big City and things like that to Nigeria. It’s a real honor to be in the company of some of our heroes.

— Nelson Kim