A Conversation with Andrew Renzi (READY FOR WAR)

I met with director Andrew Renzi (The Benefactor), on Saturday, September 7, 2019, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss Ready for War, his new documentary (which I also reviewed). In the film, Renzi follows a number of “deported veterans,” men who did not yet have American citizenship when they served in our nation’s military, were promised said citizenship for that service, but were then denied citizenship and deported for infractions (mostly for drugs and alcohol) related to PTSD and injuries incurred while in service. Beyond the ethical and humanitarian quagmire of this treatment, some of them end up being forced to join drug cartels once in Mexico (a country they barely know, if at all), given their training and experience with combat. In other words, it’s a lose-lose for everyone, including those doing the deporting, since these guys become weapons, however unwilling, used against the United States. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I met with director Andrew Renzi (The Benefactor), on Saturday, September 7, 2019, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss Ready for War, his new documentary (which I also reviewed). In the film, Renzi follows a number of “deported veterans,” men who did not yet have American citizenship when they served in our nation’s military, were promised said citizenship for that service, but were then denied citizenship and deported for infractions (mostly for drugs and alcohol) related to PTSD and injuries incurred while in service. Beyond the ethical and humanitarian quagmire of this treatment, some of them end up being forced to join drug cartels once in Mexico (a country they barely know, if at all), given their training and experience with combat. In other words, it’s a lose-lose for everyone, including those doing the deporting, since these guys become weapons, however unwilling, used against the United States. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: Andrew, how did you come across this story?

Andrew Renzi: So I had been looking for another story to tell and a lot of times I find myself interested in stories that have to do with second chances and portions of our society that get cast aside from mistakes that they’ve made when they really should have the opportunity for rehabilitation. And I heard about this phenomenon of deported veterans. I saw these two words go together and it was like, “Huh? You can deport a veteran? That doesn’t make sense to me.”

So I looked into it, I met Hector Barajas, who was living in Tijuana and I understood the issue on a bigger level and I realized it’s not an outlier issue. That was very important for me to understand, that it’s happening on a larger scale that should be talked about. And so once I talked to him and I understood what it was that he was doing to try and help these veterans out there who were getting deported, I then went to Juarez and I met with a journalist in Juarez who had access to some people who were working in the cartel. After quite a lot of digging – it took a while to get access – I also understood there was a layer of this onion that gets peeled back and you realize not only are we deporting veterans, but they’re getting recruited by the cartels because we’ve trained them as soldiers.

HtN: Your story, though very different in the specifics, reminds me a little bit of a documentary I saw two years ago at Tribeca called Island Soldier, about similar issues facing Micronesians who are promised citizenship for serving in the military. And guess what? There are issues with that, too! I’m wondering, as somebody who met all these men who are now deported, what is your insight into their enduring faith in the United States, nonetheless? Because that intrigues me.

AR: It’s a great question and it’s something that I always asked and always wondered, myself. It’s like, “How do you still have this faith in the country?” And I will say that a lot of the people that I’ve met with that ended up working for the cartel don’t have that faith, or at least they say, “I’ve decided that there is no hope for me to go back and I’m going to just give in to this thing that I know how to do because I was trained.”

But with regards to people that have this enduring faith, there’s this sort of beautiful sense of identity that no one can take away from them. It’s like they grew up in the United States, not as Mexicans, but as Mexican-Americans who have a strong sense of American identity. A lot of these guys grew up in neighborhoods where they felt some discrimination, but then when you go to the military, across the board, they all say, “That goes away. You’re in a bunker with anybody and you are brothers and sisters in this thing that you’ve decided that you need to be a part of and that you’re going to be there for each other no matter what.” And you end up with this incredible sense of identity on a nationwide level.

You feel that you are a part of something and that you are contributing to that and that just doesn’t go away. Even if the bureaucracy of that place that you swore to protect turns its back on you and wrongs you, there is still this sense of identity that they hold very dear to themselves. And I found that just to be so inspiring, to hear you have a guy like Hector, for 14 years, he’s been deported and he’s still saying, “I want to go back. I love my country. I would do it again if I had to.” It was confusing but inspiring at the same time.

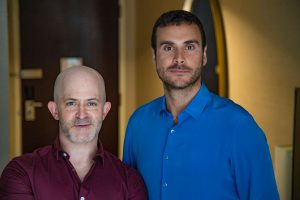

Lead critic Chris Reed and director Andrew Renzi

HtN: Right. It’s so interesting that it’s their military service that bonds them to the United States and makes them feel American, and yet that’s not enough.

AR: Yeah.

HtN: Were there times in the filming when you felt in danger? Because when you’re following “El Vet,” speaking of those who are now working for the cartel, it seems like you could be placing yourself in danger. I don’t know how much you trusted the situation or if there were things that didn’t end up in the movie, and certainly we see horrible footage of things happening that I believe El Vet has filmed, but were there times when you felt unsafe?

AR: Absolutely. There was a two-year long process of making this movie. We filmed with quite a few more people that didn’t end up in the movie. We were in situations that we weren’t able to film, and there was a process of trying to decide, “Am I pushing this too far? Is something going to happen to me?” I will say that I had a bag over my head for three hours driving into the countryside without any understanding that I was going anywhere, and for that drive I was like, “I just went too far. My cameraman and I are going to die.”

So, yes, the answer to your question is yes. I would say that I never felt as though I crossed some sort of cavalier cowboy line to go do something that felt like I shouldn’t have been doing. I definitely felt like I was searching for a story that was important to me and the decisions that we made made sense to tell that story. But there were elements of danger that I’ve never felt before in my life and I kind of hope I don’t feel again, even though there is a thrill to it.

HtN: Yeah. I don’t know if I would do that for a story, but then again, journalists often do that…

AR: Yeah, for sure.

HtN: …when they’re speaking of war, when they’re on the front lines. Not to keep on mentioning other documentaries, but I’m sure you’re familiar with Matthew Heineman’s Cartel Land.

AR: Of course.

HtN: Watching that, he’s insane, and then there’s another film, This Is Congo, set in the middle of a war.

AR: Yeah, that, too.

HtN: So, you’re a little more reasonable. (laughs) Do you have any sense, with this experience, about the intractability of the drug problem in Mexico, with the cartels? Because I’m fascinated by the fact that this country, just to the south of us, that has a functioning government, and there are parts of Mexico that are perfectly fine, has these border regions, or at least the ones where El Vet is, that seem horrible in terms of cartel activity. Did you gain any insight into that?

AR: Oh yeah. At the end of the day, it’s our insatiable appetite for drugs that is fueling this. There’s an appetite in the United States for a product that basically can only come from Mexico because it’s not coming domestically inside of our country, because the manufacturing is next to impossible. And so it won’t ever go away until that changes to some regard.

A really unfortunate byproduct is that there’s now a horrible drug problem in Mexico on the border, specifically really just on the border. Prior, there really hadn’t been that big of one because it’s a very Catholic country. There are very strong principles with regards to that stuff. But now the borders are just ravaged by drugs and that just increases the activity for cartels. And especially now, with El Chapo in jail, there’s sort of this splintering of all the factions. It’s a messy, messy world right now down there. It’s not organized, it’s not straightforward, it’s everybody fighting amongst each other and fighting for small, little bits of territory. So, it’s very violent. It’s the most violent year that Mexico’s ever had.

And so I think that the insight that I gained is that you have to look at it from the top down, that there’s this problem that’s up here. It’s really not this thing of all these bad people are coming into this country, they’re bringing bad things. It’s like, “No, we want it.” You know? And so I don’t know what the solution is.

A still from READY FOR WAR

HtN: So the United States is, in a sense, doubly responsible now, because not only is it our appetite, but also we’re now deporting people with the skills to work in the cartels if they’re faced with a life or death choice.

AR: Exactly. It’s no different than giving guns to the Taliban, to a degree. It’s kind of like funding a war that we’re fighting at the same time.

HtN: Yeah. So, you have people like that California politician, Nathan Fletcher, working to help deported veterans, and Senator Tammy Duckworth, both of whom are in your film. The outrage is palpable because they feel like these are their brothers. How involved is Tammy Duckworth in these issues?

AR: Incredibly. She’s a trailblazer. She’s introducing policy on her own and she’s going to be the one, I think, that changes it.

HtN: Great! Now, you’ve made both nonfiction and fiction work. Can you describe, as you see them, the different challenges for one particular kind of filmmaking over another? I know it’s apples and oranges, but…

AR: It’s a great question because it’s not, and that’s kind of the thing that I want to approach documentaries with, is that there’s always been sort of the documentary paradigm that’s existed for a very long time. “How do you make a documentary?” And then this is the way that we make it. Even when some of my favorite fiction directors make a doc, they kind of make it within that framework of what a doc is supposed to be. And I think now, with documentaries having this sort of real moment where people really want to pay attention, there’s no reason why the aesthetic principles, the craftsmanship, should be any different. And so I think that people can consume documentaries now in the same way that they would fiction film. And I try to approach it that way.

And I love the idea of taking the aesthetic principles that I have and pushing my aesthetic as far as I can and trying to tell a story in real time, just like a fiction movie would, but it being real. That’s a challenge that I love, and I think that we will see a shift in the way that we consume documentaries to be closer to the way that we used to consume fiction films because you can tell stories now. It’s readily available. You can do it. The equipment’s there. You just need to basically make the effort and I think that a lot of people are going to make that effort to spend two years telling a story that looks like a fiction film.

HtN: Well, that’s a great place to end. Thank you so much, Andrew.

AR: Thanks!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?

Rolo

I wanna thank the both of you it’s 5 a.m. on a Friday morning I am very choked up and shedding a tear.Just watched Ready for Documentary I was I still am very upset El Vet was murdered in Mexico it’s so fucking unjust I could actually feel his heart breaking again towards the end when he asked about the other vets getting to come home. And I’ve heard a trend down on the front eras when a Veteran is deported the Mexican government sells that info so there owls have eyes on them the moment they’re crossing Texas. Groups like CDN and the Gulf are using them to replenish their numbers. It just flat out sucks!

Christopher Reed

Hi, Rolo!

Thanks for reading and watching the film. It is very moving and upsetting, indeed. I can’t believe we do this, both to them and to us, as well (given what their deportation ultimately means). It’s an important film.

Best,

Chris