A Conversation With William Kirkley (ORANGE SUNSHINE)

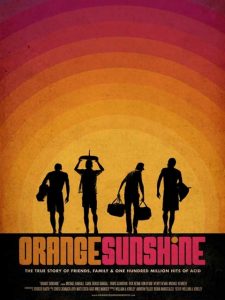

I met with director William Kirkley at the Maryland Film Festival on Thursday, May 5, 2016, to discuss his documentary feature Orange Sunshine, about the history of The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which has been making the rounds of the film festivals (including SXSW, previously), and for which I also wrote a review. Here is a condensed digest of that conversation.

Hammer to Nail: You were 10 years in the making of this film, according to the press notes. What attracted you to the project? That’s a lot of time! Was it worth it?

WK: (laughs) My father-in-law knew of the group. He lived in Laguna at that time, in the ‘60s, and shared these stories with me, while I was making my first documentary in New York. My wife and I, we were living in New York – I was making Excavating Taylor Mead – and he would write me letters and tell me these stories. And I’m from Orange County, I’m from where the story takes place. I’d heard about this group, and that’s where the initial interest came from.

I’m obsessed with California history, and especially that of Orange County and Southern California: I can just get lost in old photographs and look at them all day. So this really appealed to me. Laguna Beach has this magical quality to it. I don’t ever use that term for anything else, but it really has this magical quality, and I wondered if this group had an influence on that thing that I love so much about Laguna Beach.

HtN: You mention – again, in the press notes – the lack of archival footage. So your film has a fair amount of reenactments, and I appreciate how seamlessly you blend them with the rest. How much of your film, percentage-wise, would you say is reenactments?

HtN: You mention – again, in the press notes – the lack of archival footage. So your film has a fair amount of reenactments, and I appreciate how seamlessly you blend them with the rest. How much of your film, percentage-wise, would you say is reenactments?

WK: 80 percent.

HtN: Wow!

WK: It’s a historical documentary, and I’m up against it from the beginning, with talking heads, so I had always planned on doing recreations. With the interviews, what I did was, I shot them with two cameras, but I always shot one a little bit tighter and just kind of roaming, hand-held, and that way it would kind of blend a little more seamlessly into the hand-held “home movie” look I was doing …

HtN: So you would use that for the transition point before you would go into the hand-held re-enactment?

WK: Yeah, yeah… to kind of keep things flowing, right? To kind of make those transitions easier. So from the very beginning that had always been my plan. I was hoping I’d be able to get good archives… but they only had about 50 photographs, and there was no film of them at all, whatsoever. Being drug smugglers, they naturally wouldn’t allow themselves to be photographed

So I’ve been doing film now for almost 20 years, and when I started, film was the only option when you wanted to shoot something like music videos, or short films, so I shot a lot of Super 8. And I love film. I love just the texture and quality of film. It’s something that you just can’t replicate.

HtN: So the reenactments were done…

WK: I shot on Super 8. Most of them.

HtN: And then when you were doing the interviews, what cameras did you use?

WK: I shot a [Canon] 5D Mark III and a Canon C100.

HtN: Those are good, inexpensive, but very high-quality cameras…

WK: It does the job.

HtN: So Super 8, and then high-def… although the C100, does that shoot 4K?

WK: We shot in 2K.

HtN: Got it.

WK: And then there are a few cinematic moments that are kind of recreations, but don’t fall in that Super 8 world… they don’t look like the home movies. This movie always felt like a narrative movie to me – I always saw their story as a narrative – and there are just these scenes that played out in my head that I just had to put on the screen when I heard these stories, even if they didn’t fall under that rule of using Super 8 for the home movies. That would be like Johnny [Griggs] running, in the beginning, in the street, or Carol [Griggs], on the floor, after she’s been dosed, and we shot that on the Alexa Mini.

HtN: So given the ongoing conversation about hybridity in documentary filmmaking, have you had anyone take exception at the fact that so much of the film is reenactments?

WK: No. Nobody has talked to me about that. There are some film festivals that we didn’t get into, and I wonder if it’s because of the hybrid nature of the film, or if it’s the subject matter.

HtN: On the other hand, your brand of hybridity is quite different than, let’s say, that of another film I reviewed, from this year’s Sundance Film Festival, All These Sleepless Nights, which follows two young men in Poland in the year after they graduate from school, and where every scene is directed. That’s a hybrid documentary. Your film is just using staged elements to tell an historical story. I don’t really consider yours a hybrid; I was just curious. On a different note, you also mentioned that you had trouble gathering all of the talking-head interviews that you needed. Were there people who were hard to get a hold of or who didn’t want to cooperate with you?

WK: Yes! Everybody in the film, almost. (laughs) So this took 10 years. After 7 years, I had conducted 25 interviews, and every time I conduct an interview, it’s at least 8 hours long, and oftentimes 2 or 3 days… so 16, 20, 24 hours of material. And with the group, I started at the bottom, kind of like with the street-level dealers, and worked my way up. The people at the top – Mike [Randall] and Carol – were very private people, and they had never shared their story before. They had seen their story get sensationalized, and that’s what they were worried about… people focusing on the wrong elements and telling their story incorrectly, and so they wanted nothing to do with me or the film.

But they were very nice. And I would meet them every few months, every 6 months …I’d drive up to San Francisco. I’d have dinner with them, I’d bring my family and we’d all get together. And they’d be, like, you’re really sweet, but we’re not going to do the film. And I knew… it was their story, and I was determined to get them.

But after 7 years, I had a completely different film cut, and pretty much finished, with a whole different set of characters, but it wasn’t Mike and Carol and Travis [Ashbrook] and Ron [Bevan] and Wendy [Bevan] – the people who are in the film now – and who were really at that core, the people who founded the group. Especially Mike and Carol. I knew their love story, and I knew that that’s how I wanted to position the film. I had more of like a fun drug smuggling tale.

And after 7 years, they finally said yes. At which point, I knew I didn’t want to take their story and try to fit it in to what I already had, so I took everything that I had and I put it on the shelf and I started over. With the exception of [Former Laguna Beach Chief of Police] Neil Purcell. His timing, cadence and what he brought to that interview I had done in 2007, I knew I couldn’t replicate.

HtN: Interesting that you mention Neil Purcell, because I really like how you included law enforcement in the film. Sometimes, when one is telling a story, and there are alternate points of view, depending on where one’s sympathies lie, you leave them out. I really think it makes your film richer to include Purcell. Did you debate not doing that, to have it just be the Brotherhood?

WK: I did not. For one, with the Brotherhood, I wanted to give them a certain level of agency over their story, even though they didn’t tell me how their story should be, or had any influence over how I told the story, nor did they ask me to take anything out when I showed them the first rough cut. Most of the stories we’ve heard about drugs in the ‘60s have heavily leaned towards law enforcement, and we know that story. It’s been told so many times before. We know what that perspective is. So I wanted to have that balance. I do feel a responsibility. I’m a parent. I can’t glorify drug use too much. But I think the film is a healthy way of starting a conversation about that.

HtN: I love the work of your DP [cinematographer], Rudi Barth, who was also your production designer. How did you find him?

WK: Rudi and I have worked together on commercials for a long time; I did art direction and he did production design. And he DP-ed the interviews, and then when it came to the recreations, he took on the job of production designer, and I did DP and camera. It’s synchronicity: we work wonderfully together.

HtN: Well, you’re a great team. Congratulations on the film!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)