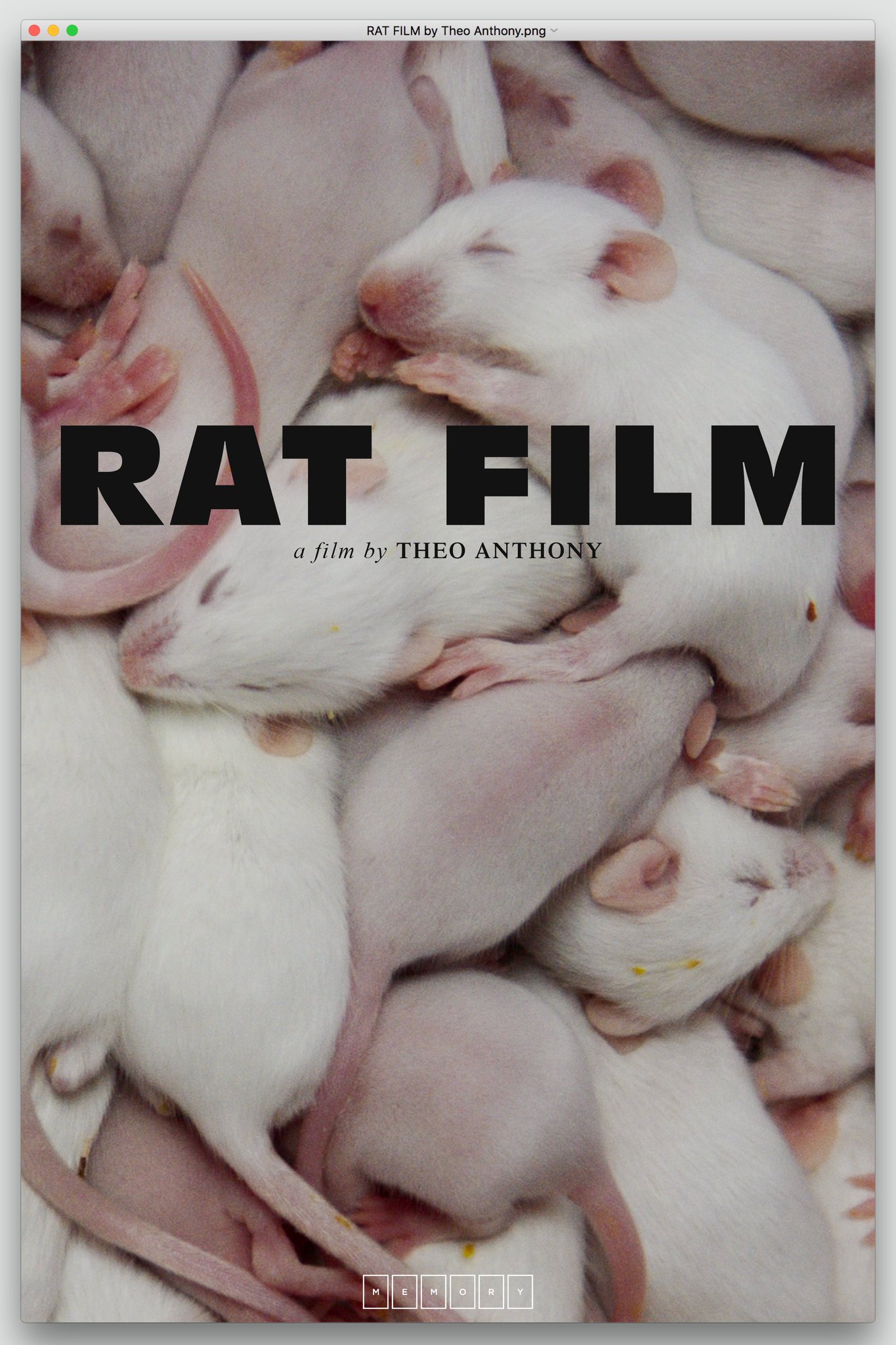

A Conversation With Theo Anthony (RAT FILM)

I met with director Theo Anthony on Saturday, March 11, 2017, at SXSW, to discuss his new film, the experimental feature documentary Rat Film, which I also reviewed. The movie explores the fascinating history of rat populations in Baltimore (where this film reviewer also lives), and how their numbers and locations are directly related to the decisions made by urban planners in the first part of the 20th century. The story may be set in Baltimore, but it raises issues germane to all urban environments. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation.

Hammer to Nail: In your director’s statement, you write,” I am interested in making films that explore how subjective reality is commodified to fit outsider’s narratives of consumption and production.” How do you feel you are doing that in Rat Film?

Theo Anthony: I wrote that in reference to my work as a journalist, in particular, being an outsider – a very naïve outsider – going into a situation and taking someone else’s story and injecting it into a market that cares very little about the well-being of that person. I think, with Rat Film, I am dealing with those same issues, but it’s a film about…it’s a film about maps, and it’s a film about people who make maps and pass them off as objective reality. That objectivity is actually a very trenchant power structure that is very subjective and has a lot of blind spots, has a lot of biases, which come out in the map. And in making a film about that, I realized that when I was going out and meeting these people, and making them fit my narrative…they were pawns in my story.

As a director, as an editor, you’re moving people around. It is a very exploitative, extractive act, and it has to be questioned as it goes along. With Rat Film, there’s a lot of questioning of who is making the map of the film. I’m obviously a white dude telling black history, never at any point speaking for black experience, which is, I think, my bottom line. I never want to speak for someone else’s experience – I try to give them a platform from which to speak – but with Rat Film, it’s about looking at that expectation of extraction and moving people around and really weaving that into the rest of the film. Any documentary structure is inherently problematic. You are placing people in a story, and they’re not living a story, they’re living their lives, and you’re putting them as artificial constructs and that’s been used in the past to very problematic and very tragic ends.

As a director, as an editor, you’re moving people around. It is a very exploitative, extractive act, and it has to be questioned as it goes along. With Rat Film, there’s a lot of questioning of who is making the map of the film. I’m obviously a white dude telling black history, never at any point speaking for black experience, which is, I think, my bottom line. I never want to speak for someone else’s experience – I try to give them a platform from which to speak – but with Rat Film, it’s about looking at that expectation of extraction and moving people around and really weaving that into the rest of the film. Any documentary structure is inherently problematic. You are placing people in a story, and they’re not living a story, they’re living their lives, and you’re putting them as artificial constructs and that’s been used in the past to very problematic and very tragic ends.

HtN: One of the things I really appreciate about your film is that however you feel about that traditional documentary structure, and however much you play and experiment with that structure, you still deliver some real documentary content. We learn a lot about the history of urban planning in Baltimore. I’m curious how you arrived at the structure of the film? That combination of the traditional and the experimental, and by that I mean the video games, that shot you hold on forever of the guy with a rat on his shoulder, the car race – I still don’t know what that footage means…

TA: (laughs) Me, neither … no, I’m kidding …

HtN: …but it all makes for this interesting tapestry. So how did you come about that structure?

TA: The structure is a really organic representation of my discovery of the film and my discovery of these materials, and the form that that takes, which is very true to how I discovered these things. So I think that I do engage in a familiar documentary talking-head mode, at times, but I also put in video-game components, I put in music-video components, I put in screenshots from Google Maps. I have no allegiance to any one style. I’m the opposite of a purist when it comes to any of that.

With all these different forms and structures, I don’t put any basic value of one above another, but I think they can all serve different purposes and there are different benefits to each of them. For me, I’ll use whatever comes naturally. And I think that the most interesting thing is setting these things in conversation with each other in a way that they build on each other, but also sabotage each other. You have the appearance of a very objective narrator, but there are other forms and other strategies that totally undermine the objectivity within it. So I like setting all these forms against each other, in conflict.

Theo Anthony

HtN: Let’s talk about that narrator for a second, because I’m not sure I would use the word “objective” to describe her. Something about the way you take the actress Maureen Jones’ voice – whether it’s purely in your direction of her, whether you’ve added a filter to make her sound mechanized – it’s almost as if we are listening to an ever-so-slightly ironic Siri. There’s irony there, in that almost monotone. At least I feel it. How did you come about that tone?

TA: I’m really happy that you felt that way, because it was definitely one of the goals of that approach. In the expectation of the traditional documentary talking head or narrator, there is this “oh, let me tell you this story” and “this story will not be questioned” and that’s floating above the whole film, like this god face. And I think that maybe it’s an ironic god, but it is a very god-like voice.

When I was editing this, in a cabin in the woods, by myself, and I was writing it as I went along, and I don’t like the sound of my own voice, and I don’t use it, and so I said I really need to hear these words with the image. So I actually typed up the whole script and had Siri read it. And that was in the film and made it until the very final cut. But it was too much; it was too ironic, too gimmicky.

And then I found Maureen Jones, and she was such a pro, like a finely tuned instrument. And so much of it was just peeling back the performance of the empathetic voiceover artist, and saying, “I want you to be as cold as possible, as calculated as possible, as sterile and clinical as possible.” And there is an ambiguous tone – I don’t know if I’d say ironic – and it is very cold. I love that it can be clinically describing data and then slide into the poetic, and that you’re feeling these emotions through such a cold device. Instead of it saying, “Here is how you should feel,” it’s like you’re hearing the opposite of how you feel.

It’s a similar strategy to what I did with the maps, at the end. That’s probably the most emotional part of the film, in a lot of ways, seeing those maps, layered on top of each other, and that’s…data. You’re looking at info-visuals, and it’s really cool that you can have this reaction through the artifice of something that is normally thought of as extremely cold and distancing. So that, to me, is really interesting.

HtN: Well, you set that up so well, earlier, because you return to the maps that show urban planning, segregation and rats, many times, and we watch that idea develop, which is why I think it’s so effective. Did you alter Maureen Jones’ voice, in any way, or is it all through performance?

TA: We took out breaths.

HtN: OK, but that’s just editing…well, no, actually, that would be interesting, because it would make her sound more machine-like.

TA: Yeah, exactly, so we took out the breaths, and she’s a pro, and contains her breaths, anyway.

HtN: But otherwise there’s no filter.

TA: I mean, there’s like a slight filter, but it was only to take out some of the bass. But it was very normal mastering stuff, no filter. She’s so good. Once she got it, she got it. She’s this sweet woman from Calgary, who was calling me “honey” and stuff. Like the total opposite.

HtN: Funny! So, your film tells not only the history of the rat in Baltimore, but also of urban planning, as we just discussed, and how the two intertwine. Has this subject always been of interest to you, or did you first start thinking about rats, or about urban planning? How, ultimately, did you come by this subject?

TA: I mean, my dad’s an architect, and I’ve always been interested in how cities are made, but I never studied it. This was my intro to urban planning. This film was like a chart of that course. Honestly, the inspiration for the urban-planning part was that I used to live on Greenmount Avenue [in Baltimore], on 39th and Greenmount, and people in Baltimore know that that’s up against the Guilford/Homewood community. Greenmount Avenue is like my favorite street in Baltimore. I walk a lot, I walk all over the city, and you walk up and down Greenmount, and if you’re facing North, on the left-hand side are multi-million-dollar Victorian homes, and on your right-hand side are boarded-up row homes. It’s such a stark contrast.

And you see these things, these coded forms of a racist past. All the houses on the right are a grid system, with stop signs and very geometric, while on the left, all one-way streets, winding, only two entrances. You can even see where they planned to have turns into the community, but the community planted over it with a flower bed. They said, “We’re going to close you off, and make it look nice.” It was just a very earnest exploration of why cities look the way they do. The material was there. There’s so much good writing about Baltimore, and rats, and all these things, and so I dove in and it was not accidental. It was a very intentional plan.

HtN: I know that area well, and I’ve driven along 39th many times, and I’ve always been struck…there are actually a number of places where it transitions from wealthy enclaves to obviously not-so-wealthy neighborhoods. So it’s a really odd street, actually.

TA: And MLK Boulevard…

HtN: Yeah, MLK, as well. There are a number of places like that. I live on the edge of the neighborhood of Roland Park, and as you walk down University Parkway, towards the city, you start to see the transition from upper-class to the sort-of middle-class buffer, and then it goes further…

TA: And you start to see these things and you go to cities and eyes were opened. When you start to see the city as this living history, and not just this accidental “oh, I moved into that neighborhood” thing and question “why did I move to that side of the street instead of that side of the street,” you just see all these forces in action. I learned so much just by walking. These are very basic questions.

HtN: And again, it all adds up to quite an original film. So, you’re not from Baltimore, originally. What brought you there.

TA: I grew up in Annapolis [Maryland]. Very different town. Really nice place to grow up. And I guess as a teenager, Baltimore was the place to which I used to sneak away to go to shows and stuff. It was like my escape. It was the first time that I saw an art scene. Some of my earliest, best memories of music are of Dan Deacon shows when I was 16. It’s so cool that we are now staying at the same Airbnb, touring with the film. It’s wild.

So that scene was like the first time I ever saw what an art scene could be that wasn’t existing for some New York City profit drive. Artists supporting each other, working for each other and with each other. So I moved away, I went to college, and then I moved back for a year, then I moved abroad, went to the Congo, came back, and have been in Baltimore for like 3½ years.

HtN: It’s a good city for the arts.

TA: Yeah. I love it.

HtN: And cheaper than New York.

TA: Much cheaper.

HtN: Final question. So what is that car-race footage about? What does it mean to you? I didn’t mind it, at all, but I was just trying to fathom what it was.

TA: Yeah, a lot of people are really confused by it, but I love that no one really knows what it is, and they can never articulate it, but I think most people have the reaction of just like “oh, yeah, it belongs there.” Which is kind of cool. Just very practically, when I was making the film, I was shooting a bunch of stuff, and I was just thinking of how to…I really love the idea of framing a film in a mythic structure, like imagining your film is a myth, and constantly reminding the viewer that you’re not living that experience, but watching an artifice of experience. It’s called Rat FILM, not just “Rat.” It’s a film. Rat Film. You’re watching a film. Remind people of that, as much as you can.

For the car stuff, I was there and I was watching this drag race, and it just felt like the birth…like the life and death of the universe. This countdown and huge explosion that goes by so quickly, and everyone’s just sitting on the side. And I like to think about ideas and spectatorship and constantly questioning who are we on the sidelines of this film. For me, those racing sequences were a good way of acknowledging that and engaging with that issue.

HtN: Sure. On another note, I think rats are cute, by the way. And I have thought of having a pet rat, but one thing I can’t stand is the tail. Not that they can help it.

TA: Freud writes a lot about that.

HtN: (laughs) About the tail?

TA: (laughs) Yeah.

HtN: But they’re cute, and I’m glad you included pet rats in the film, too.

TA: I think rats are great. I think rats are really admirable creatures. If I were in a place for more than a week at a time, I would consider getting one. My point wasn’t to damn or save rats.

HtN: Well, I think that by including the pet rats, you keep a variety of points of view in the film.

TA: Yeah, they mean a lot of different things to different people.

HtN: I know people who are just disgusted by them, and I say, “It’s a mammal!”

TA: They’re so cool. They’re very resilient, incredible creatures. I mean, they’re not my favorite. I don’t have a tattoo of a rat or anything…

HtN: (laughs) Well, Theo, thank you so much.

TA: I appreciate it!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)