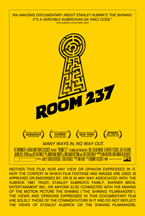

A Conversation With Rodney Ascher (ROOM 237)

(Room 237 is now available on DVD, Blu-ray, and at Amazon Instant through MPI Home Video.)

Film theory: healthy academic brain exercise or ludicrous waste of time? According to Rodney Ascher’s Room 237, why, it’s both, actually! To sincerely explore this question, Ascher and producer Tim Kirk set their targets on Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 entry into the horror canon, The Shining. Kubrick’s private nature, as well as his superior, though comparatively infrequent, output, has made his entire oeuvre a target of obsession for cinephiles across the globe. Yet The Shining has birthed a particularly dense and often gloriously head-scratching amount of interpretation: was it Kubrick’s apology to his wife for lying to her about shooting the fake moon landing footage? was it a middle finger to the book’s author Steven King? was it a pointed metaphor about the Nazi holocaust and/or the white man’s systematic slaughter of Native Americans? These theories—and so many more—make The Shining the ripest source material for a clever cine-investigation such as this.

Untrained as a documentarian, Ascher takes an inventive stylistic approach to his material: while we hear several experts/theorists/fanatics espouse their theories, we never once see them; instead, the visuals consist solely of clips from The Shining and other films and found footage sources. This results in an at times unsettling, more times hilarious, yet always thrilling, ride. Featuring astonishing musical contributions from Jonathan Snipes, William Huston, and The Caretaker, Room 237 is one of 2013’s most whip-smart and fiercely entertaining releases. If only more nonfiction films were like this. The day before his film was set to open in NYC and VOD (Friday, March 29, 2013, through IFC Midnight), I spoke to the LA-based Ascher on the phone to figure out how this dazzling film came to fruition. But first, watch this truly great trailer:

Hammer To Nail: Did your own obsession with The Shining inspire this movie? Or did you stumble upon all of the discussions surrounding it and realize that this movie as much as—or perhaps even more than—any other, would make for a great exploration of psycho-theoretical-cine-fandom?

Rodney Ascher: Well, I guess both. I’ve always been a Kubrick fan and I’ve always loved The Shining. So when my friend Tim Kirk [Room 237 producer] discovered one of these essays online, I was just so ready for it. So the project started when he discovered this kind of writing about The Shining, and then the two of us spent a year researching as much of it as we could. In the course of that, you know, we asked ourselves, “Is this the best film to do this with? Has another movie generated more and more interesting analyses than The Shining?” But, as fate would have it, none of them did. The Shining had the most stuff, but it was [also] movie I loved enough that I could sit and watch it one frame at a time for a year and not go crazy myself.

H2N: I saw it back at Sundance, where the consensus seemed to be that 1) the movie was totally awesome, but 2) there was no way in hell it would ever see the light of day due to rights issues. I gather this is something you worked out along the way, or at least before you premiered it at Sundance—and I’m not talking about just clearing The Shining clips, as you have so much other stuff in there.

H2N: I saw it back at Sundance, where the consensus seemed to be that 1) the movie was totally awesome, but 2) there was no way in hell it would ever see the light of day due to rights issues. I gather this is something you worked out along the way, or at least before you premiered it at Sundance—and I’m not talking about just clearing The Shining clips, as you have so much other stuff in there.

RA: When we started, it was just a fun project that we were working on, on our own time, because we were personally fascinated with the subject matter and this was a style I enjoyed working in, which we could do without initially spending a ton of money. But at the rough cut point, when it seemed to be coming together, we both started looking around for precedents where other people had done sort of similar things. And there are a couple out there. And then our executive producers came on board: P. David Eversoll and Todd Hughes. They had just finished their movie Hit So Hard, about Patty Schemel, the drummer from Hole, and they had really gone through clearance boot camp for that thing. There’s a lot of pop music in it, and TV clips and things, so they were a giant help in holding our hands through the clearance process.

H2N: Did you consider most—or all—of the clips “fair use?” Or was there another umbrella term under which you were able to work?

RA: There is a lot of fair use in the movie. There’s also stuff that we licensed and some of it is public domain. We worked with this law firm that really specializes in this stuff and who were able to help nail down what we could and couldn’t do.

H2N: Was there any moment along the way where you thought you had the film finished—or at least the film you wanted to make—but had to lose something?

RA: No. My panic was that it wouldn’t make sense and nobody would like it. [H2N laughs]

H2N: As for your decision to never actually show the interview subjects, was that a conscious reaction against “talking head” documentaries, or was it a more practical decision in that maybe a subject didn’t want to be filmed on camera?

RA: It wasn’t dictated by any of the [subjects]. It was a style I’d worked with before on a short, and I liked the way that the short wasn’t necessarily a straight-up documentary but more of a weird sort of remix/montage dreamlike exploration of a childhood phobia. Before these projects, I had done a lot more weird short films and remixes, and a couple music videos, but not a ton of documentary stuff. So actually, the weird thing is that this has documentary elements in it at all. You know, a lot of strange things start to happen when you don’t see the talking heads. For the purpose of this project, I kinda liked the way that that worked.

RA: It wasn’t dictated by any of the [subjects]. It was a style I’d worked with before on a short, and I liked the way that the short wasn’t necessarily a straight-up documentary but more of a weird sort of remix/montage dreamlike exploration of a childhood phobia. Before these projects, I had done a lot more weird short films and remixes, and a couple music videos, but not a ton of documentary stuff. So actually, the weird thing is that this has documentary elements in it at all. You know, a lot of strange things start to happen when you don’t see the talking heads. For the purpose of this project, I kinda liked the way that that worked.

H2N: Were you in the room with your subjects when you did the interviews? I mean, obviously not the one guy who told you to hold on so he could go quiet his kid. [RA laughs]

RA: I was never in the same room with these folks. I just mailed them audio recorders and then I talked to them through maybe a Skype on my end to have a backup of the recording and a clear line of my own voice. I spent a couple minutes at the top of each interview talking them through, you know, “Okay, is the counter moving? Can you see the levels going up and down? Okay, it sounds like we’re good.” [both laugh] Again, this was a movie that had no financing at the beginning. Tim and I actually pitched it to a couple of producers who liked it but never signed on the dotted line. So we were just financing it out of our pockets for the longest time.

H2N: What makes the movie so alive and fun is how you skirt a really tricky line throughout, like you’re clearly having fun with these theorists, but you’re never making outright fun of them. Was that something you were sensitive to during the edit?

RA: A little bit. It was important to me that there would be humor in the film. And sometimes it’s a hard line to walk, but I hoped it would never come across as making fun of them in a mean-spirited way. A lot of the humor would come from unusual juxtapositions, or just going so deep down one specific train of thought.

H2N: Did you play the note card game? Watching it again the other night, the construction of this thing was pretty disorienting to fathom. Did you work from an instinctive place or did you very intellectually break down the narrative timeline as you worked through it?

RA: We didn’t use note cards. We used post-it notes. [both laugh] I would work on a ton of little sequences separately. So, on my computer, there would be a folder for each of our interviewees, and each one would have 10 or 15 self-contained segments that were one-to-seven-minutes long. Then, at a certain point, Tim and I put them all up on the wall and sort of clumped them together and tried to find the flow and connections and structure that made sense for the way we wanted to tell the story.

RA: We didn’t use note cards. We used post-it notes. [both laugh] I would work on a ton of little sequences separately. So, on my computer, there would be a folder for each of our interviewees, and each one would have 10 or 15 self-contained segments that were one-to-seven-minutes long. Then, at a certain point, Tim and I put them all up on the wall and sort of clumped them together and tried to find the flow and connections and structure that made sense for the way we wanted to tell the story.

H2N: Was it a long process to get to a comfortable place or did it seem together pretty organically?

RA: It kinda came together pretty quick. With some of the bigger questions, like, “Do we do each person one at a time?” or “Can we start at the beginning of The Shining and end at the end?” Pretty quickly—it was probably only the second interview—when we realized that that was not the way this was gonna flow best.

H2N: I’m wondering if there were any particular theories or insights that you at first scoffed at but which you now actually believe?

RA: At a certain point, I think we talked about the impossibility of verifying Kubrick’s intent behind almost any of these things. And we certainly weren’t using that as criteria for what got in. What got in were things that were persuasive and interesting in part of a bigger picture. ‘Cause ultimately, this is not Rodney Ascher or Tim Kirk’s interpretation of The Shining. This is an overview of some of the most amazing things we found that were written about The Shining. And certainly, just because we’re juxtaposing very different points of view, the idea that some of them would be mutually exclusive was a [concern] that we had from the beginning. You know, how is the audience gonna reconcile that? If idea one is presented as persuasively as you can, and then idea two is presented equally persuasively—the impossibility of buying into both of them was something that we liked. Although I was actually happily surprised that more of them seemed to complement each other than I was expecting going in.

RA: At a certain point, I think we talked about the impossibility of verifying Kubrick’s intent behind almost any of these things. And we certainly weren’t using that as criteria for what got in. What got in were things that were persuasive and interesting in part of a bigger picture. ‘Cause ultimately, this is not Rodney Ascher or Tim Kirk’s interpretation of The Shining. This is an overview of some of the most amazing things we found that were written about The Shining. And certainly, just because we’re juxtaposing very different points of view, the idea that some of them would be mutually exclusive was a [concern] that we had from the beginning. You know, how is the audience gonna reconcile that? If idea one is presented as persuasively as you can, and then idea two is presented equally persuasively—the impossibility of buying into both of them was something that we liked. Although I was actually happily surprised that more of them seemed to complement each other than I was expecting going in.

H2N: I know Lincoln Center is showing The Shining as some sort of double-bill with your film, but when I watched it again the other night, rather than watching the movie right afterward I threw in Vivian Kubrick’s Making ‘The Shining’ documentary.

RA: Oh that’s great, yeah.

H2N: And I actually think if you read Room 237 as a celebration of the beautiful folly that is film theory, this might in fact make for a more appropriate one-two punch. Like, the juxtaposition of seeing people watching a movie and over-analyzing it with witnessing those who are going through the excruciating process of actually making it, it’s really fascinating. What’s your take on Kubrick? There are those who believe he controlled everything within the frame to an obsessive degree, and then many others say he worked more spontaneously and intuitively than that.

RA: Well, I mean, I do believe that The Shining is a denser, more complicated film—with references to all sorts of ideas—than a lot of movies. Absolutely, I believe that. And another way to look at that, you were just hitting on [the idea of] making subconscious choices. You know, you don’t necessarily know why you choose this prop instead of that one, or this costume instead of that one, but when you make a hundred of those decisions, seemingly subconsciously, they can very often add up to something.

H2N: Okay, my last and perhaps most pressing question: were the paranoid moon landing expert’s taxes, in fact, audited?

RA: [RA laughs] Oh, I don’t know, that’s a good follow-up. I haven’t heard.

— Michael Tully

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail