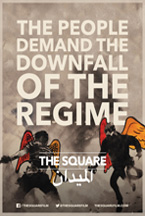

A Conversation With Jehane Noujaim (THE SQUARE)

In January 2011, Egyptian-American documentary filmmaker Jehane Noujaim (Startup.com, Control Room) started filming the anti-government protests erupting in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. This latest flowering of the Arab Spring seemed to reach a decisive climax just a few weeks later, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. Mubarak’s fall from power was a remarkable story all by itself: a long-oppressed and highly sectarian citizenry banding together to topple a dictatorship. But it was only the beginning.

In January 2011, Egyptian-American documentary filmmaker Jehane Noujaim (Startup.com, Control Room) started filming the anti-government protests erupting in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. This latest flowering of the Arab Spring seemed to reach a decisive climax just a few weeks later, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. Mubarak’s fall from power was a remarkable story all by itself: a long-oppressed and highly sectarian citizenry banding together to topple a dictatorship. But it was only the beginning.

The Egyptian Army, which moved swiftly to impose order following Mubarak’s departure, began to tighten its control of the government. Thousands of Egyptians returned to Tahrir Square, this time to speak out against the same generals who had only recently claimed to be serving the will of the people. Noujaim and her crew returned as well. By now she had decided to focus on three main subjects, all activists she met in the Square: Khalid Abdalla, the UK-raised actor who starred in The Kite Runner; Ahmed Hassan, a young firebrand who served as unofficial security for the demonstrators; and Magdy Ashour, a devout Muslim and family man who had been cruelly treated by Mubarak’s secret police for his membership in the banned Muslim Brotherhood.

The protesters’ demands for an end to military rule were met by violent crackdowns, captured in shocking detail by Noujaim’s camera. Then the Muslim Brotherhood broke away to begin negotiations with the generals, in a further setback for the pro-democracy coalition. But finally, the Army announced it would step aside once elections were held.

Any feeling of triumph was short-lived. The Muslim Brotherhood’s candidates won the parliament and then the presidency. Over the next several months, as the Brotherhood expanded its own powers and punished its enemies, the protesters kept up their vigil in the Square, with millions of others signing petitions and taking to the streets all across Egypt to protect the newborn democracy from being strangled in its crib. The Army seized the opportunity to reclaim power, turning against the Brotherhood and throwing President Mohamed Morsi out of office—which brings us up to the present day, with the Brotherhood broken, the Army holding the reins, and the entire country waiting uneasily to see what comes next.

Noujaim was there for all of it. Almost three years of shooting resulted in some 1600 hours of footage—enough for perhaps a dozen movies, which she has condensed into 100 very busy minutes bookended by the fall of two governments. Put aside any concerns that The Square will be dutiful, good-citizenship viewing material best suited for the small screen, and don’t tell me you’ve been following the news from Egypt online so you won’t “get anything new” from it. This is as thrilling a doc as I’ve seen in years, heartbreaking and inspiring in equal measure, and dramatically compelling even when the outcomes of major story events are never in doubt. The three central protagonists’ individual struggles anchor the narrative, but the wider picture—of a nation in turmoil, a region undergoing seismic change, a chapter in history being written and furiously revised moment to moment—always remains in view.

A work-in-progress cut of The Square won the Audience Award at Sundance this past January. The final version screened at the Toronto Film Festival in September and the New York Film Festival earlier this month. It begins its theatrical run on October 25, 2013, at the Film Forum in NYC, and will open at the Sundance Sunset, Laemmle Monica 4, and Laemmle Playhouse 7 in LA the following Friday (November 1st). (Go to the movie’s website for further details.) I spoke to Noujaim by telephone a few days before the Film Forum opening.

Jehane Noujaim: I grew up about 10 minutes away from Tahrir Square, my family still lives there, so what happens in Egypt affects my and my family’s life very deeply. So even if I wasn’t a filmmaker, I would’ve been in that square trying to understand what was going on. In 2007 I made a film about three women that were filming all of the corruption around the elections. It was called Egypt: We Are Watching You, and it came out on BBC and a number of channels internationally. And I at that point in time thought that we were close, the population was close to an explosion because the gaps between rich and poor were becoming so large.

Jehane Noujaim: I grew up about 10 minutes away from Tahrir Square, my family still lives there, so what happens in Egypt affects my and my family’s life very deeply. So even if I wasn’t a filmmaker, I would’ve been in that square trying to understand what was going on. In 2007 I made a film about three women that were filming all of the corruption around the elections. It was called Egypt: We Are Watching You, and it came out on BBC and a number of channels internationally. And I at that point in time thought that we were close, the population was close to an explosion because the gaps between rich and poor were becoming so large.

So when things erupted in Tunisia, and then Khaled Saeed, who was the young man that got brutally tortured by the police six months before the uprising—a Facebook page was created and millions of people signed onto it—it started to feel like we were getting close to something really serious happening on the ground. I was in Egypt at the time and I had a choice between going to Davos [for the annual World Economic Forum meeting], I had been invited there, or staying for the protest on the 25th of January when everything started, in 2011. I ultimately decided to go to Davos with my camera because I thought that would be an interesting perspective, if I was able to get access to some of the leadership of Egypt as the country was erupting.

But I got to Davos and none of the leaders showed up. And so I made my way back to Egypt as quickly as possible. Landed in Egypt and got my main camera confiscated—they were confiscating all of the cameras of journalists coming in. But a friend of mine told me to pick up a 5D, one of these Canon cameras. They weren’t confiscating them because they look like photography cameras. So I did that, but was stopped by the military police at a checkpoint; the military was already in the process of taking over. They searched the car and, I didn’t know this at the time but found out later, they saw a few of the DVDs of my previous film Egypt: We Are Watching You—not a great film [title] to see now that the country is exploding.

I was taken in for questioning and as soon as they started asking me about my political background and whether I made political films I realized, Okay, he definitely saw these films in the bag. So I tried to shove the films—I don’t know if you’ve ever been to the third world, but oftentimes the bathrooms are just a hole in the ground—I tried to shove them down this drain, and went back in for questioning, and the guy who cleans the bathroom shows up about five minutes later holding a piece of a DVD in his hand! So I was found out.

And at that point something inside of me broke. I’d just been spending the last four hours trembling, scared, scared to say what I do, scared to talk about a project that I actually thought was very nationalistic in a way because it was following these Egyptian women who were fighting for change in the country. And when that realization came over me, I just said—first of all, I’m caught red-handed so I have no choice!—but I’m just going to come clean. I told them I made this film about these amazing women, and do what you will but this is what I believe in.

I think what brought about that feeling was maybe a tiny example or a small mirror—very small in comparison to what the Egyptian people have gone through—but a small mirror of what people in that square felt like: We’re not hiding anymore. When this barrier of fear breaks and you begin to express your dreams and your hopes for change, without the fear of what’s going to happen as a result—you have to understand, we grew up in a country which had emergency law. It was against the law for more than three people to gather and talk about politics, so what was happening in that square was completely against the law.

I think what brought about that feeling was maybe a tiny example or a small mirror—very small in comparison to what the Egyptian people have gone through—but a small mirror of what people in that square felt like: We’re not hiding anymore. When this barrier of fear breaks and you begin to express your dreams and your hopes for change, without the fear of what’s going to happen as a result—you have to understand, we grew up in a country which had emergency law. It was against the law for more than three people to gather and talk about politics, so what was happening in that square was completely against the law.

So I went immediately to the Square and I had my camera, and I was just completely overwhelmed by this feeling of possibility, people who were talking with each other, Muslim, Christian, men, women, all different classes, about their hopes for a different country. And so I knew I wanted to film this and started to look for characters who could take me through the journey. Because in any film like this, you need to follow an emotional story.

Literally in the next two weeks I found all of the characters that we were to follow and met the rest of my crew. We all met each other in the Square, the DP, I met my producer there, and we all decided to collaborate and make this film together. It wasn’t something where you could hire somebody from the States to come in, you know, because by being there you were putting yourself in a very dangerous situation. So everybody that worked on the film were people that wanted to be there anyway.

Hammer to Nail: One of the things I found fascinating about the film is how it combines two modes of documentary that are usually kept apart. It’s an immersive vérité portrait and a character study but at the same time it’s very much a work of advocacy, you’re unambiguously taking the side of the pro-democracy activists.

JN: Well, the way I [work is] by trying to capture the emotional journey of characters. And we considered—we met with army officials, we met with leaders from the government, but frankly, the protesters’ story was much more interesting to me. You do see the military [in the film], we do interview and hear from military men, but I found that when I met with them, they were spouting the same kind of rhetoric that we had been hearing for so many years. And the protesters—you know, when you make a film, you look for somebody who’s about to jump off of a cliff. And they’re putting everything they have on the line to fight for what they believe in. You’re capturing this moment where people’s true personalities come through because it is such a crucial moment for them, and that’s a fascinating story to follow. So the people that were in that position were the protesters. That’s why we ended up really focusing on them. I mean, probably you would’ve found the same depth of human emotion if you had followed, say, members of the leadership who were being kicked out of the country at that time. But that was a very difficult story to get access to, and a completely different [one].

JN: Well, the way I [work is] by trying to capture the emotional journey of characters. And we considered—we met with army officials, we met with leaders from the government, but frankly, the protesters’ story was much more interesting to me. You do see the military [in the film], we do interview and hear from military men, but I found that when I met with them, they were spouting the same kind of rhetoric that we had been hearing for so many years. And the protesters—you know, when you make a film, you look for somebody who’s about to jump off of a cliff. And they’re putting everything they have on the line to fight for what they believe in. You’re capturing this moment where people’s true personalities come through because it is such a crucial moment for them, and that’s a fascinating story to follow. So the people that were in that position were the protesters. That’s why we ended up really focusing on them. I mean, probably you would’ve found the same depth of human emotion if you had followed, say, members of the leadership who were being kicked out of the country at that time. But that was a very difficult story to get access to, and a completely different [one].

H2N: At one point Khalid says, “Revolution is not the same as politics”…

JN: I think that’s a very interesting line, the difference between revolution and politics. Not many people have experienced revolution, including myself, so what exactly is it, what’s the definition of it? Khalid described it as the ability to effect a massive amount of change in a short period of time. And to be completely steadfast in principles in your demands for change. It took me a while to understand that. But then when you see people being run over by tanks, and the government is lying [about it], you start to see very quickly that unless you stand up with absolutely no compromise for some very basic human values and human rights and fight for them—we know that rights are never given, they’re always taken—and don’t get sucked into the political debate of who is going to take power, right? There’s a step that goes before the politics, and then there’s a stage where you can go into the political [realm]. But there needs to be this sort of sounding period first, where the constitution is written, and this is what the protesters keep referring to. I mean, how can we be electing a leader, how can we be talking about this political fight, when we don’t even have a constitution that determines what the role of parliament or the president is going to be? So this is why the revolutionaries were sitting in the square saying, No, we’re not ready for elections. And that’s very confusing to [people in] the West, who were looking at the situation and saying, But elections mean democracy! Right? Why don’t you guys want elections? Why are you boycotting elections? Because if you elect the Muslim Brotherhood, for example, this is what happened, the Muslim Brotherhood has the ability to create a constitution which then becomes a tool of the Muslim Brotherhood rather than a constitution which protects all of the people—then you have failed in achieving the demands of the revolution.

JN: I think that’s a very interesting line, the difference between revolution and politics. Not many people have experienced revolution, including myself, so what exactly is it, what’s the definition of it? Khalid described it as the ability to effect a massive amount of change in a short period of time. And to be completely steadfast in principles in your demands for change. It took me a while to understand that. But then when you see people being run over by tanks, and the government is lying [about it], you start to see very quickly that unless you stand up with absolutely no compromise for some very basic human values and human rights and fight for them—we know that rights are never given, they’re always taken—and don’t get sucked into the political debate of who is going to take power, right? There’s a step that goes before the politics, and then there’s a stage where you can go into the political [realm]. But there needs to be this sort of sounding period first, where the constitution is written, and this is what the protesters keep referring to. I mean, how can we be electing a leader, how can we be talking about this political fight, when we don’t even have a constitution that determines what the role of parliament or the president is going to be? So this is why the revolutionaries were sitting in the square saying, No, we’re not ready for elections. And that’s very confusing to [people in] the West, who were looking at the situation and saying, But elections mean democracy! Right? Why don’t you guys want elections? Why are you boycotting elections? Because if you elect the Muslim Brotherhood, for example, this is what happened, the Muslim Brotherhood has the ability to create a constitution which then becomes a tool of the Muslim Brotherhood rather than a constitution which protects all of the people—then you have failed in achieving the demands of the revolution.

H2N: You balance the scenes of protest and violence and action with more reflective or introspective scenes, debating over strategy and tactics, planning and philosophizing—can you talk about finding that balance? In the shooting and in the editing?

JN: In the filming it’s this process of trying to keep up with the story, running after your characters and trying to get the best footage that you can in order to tell the best possible story, and we had an incredible team of talented filmmakers who were following all of the characters. Cressida Trew, Khalid Abdalla’s wife, was following Khalid and a couple of the other characters, and so we were able to get very intimate moments of him. I’m not sure whether he knew when he signed on to be a character that he would wake up with a camera in his face in the bedroom! I mean, she’s very talented but that was a wonderful advantage, that she was able to go home with him [to get that footage]. So that’s how those personal moments came. Ahmed was basically living with us at our offices, which were five minutes away from the Square. Our office became this place where a lot of the revolutionaries lived and worked so we had constant access to him both in the activist place in the Square and also in the quieter debating moments. And Magdy as well, we were spending a great deal of time with him. All of this comes down to building a kind of trust with your characters so that you can film both sides, them in the public sphere but also them in the private sphere, doubting what they’re doing, questioning what they’re doing. That’s really important to see because you don’t want to make a film that just shows the high moments, the successful moments. To really understand what change takes, it involves going deeply into the failures as well.

JN: In the filming it’s this process of trying to keep up with the story, running after your characters and trying to get the best footage that you can in order to tell the best possible story, and we had an incredible team of talented filmmakers who were following all of the characters. Cressida Trew, Khalid Abdalla’s wife, was following Khalid and a couple of the other characters, and so we were able to get very intimate moments of him. I’m not sure whether he knew when he signed on to be a character that he would wake up with a camera in his face in the bedroom! I mean, she’s very talented but that was a wonderful advantage, that she was able to go home with him [to get that footage]. So that’s how those personal moments came. Ahmed was basically living with us at our offices, which were five minutes away from the Square. Our office became this place where a lot of the revolutionaries lived and worked so we had constant access to him both in the activist place in the Square and also in the quieter debating moments. And Magdy as well, we were spending a great deal of time with him. All of this comes down to building a kind of trust with your characters so that you can film both sides, them in the public sphere but also them in the private sphere, doubting what they’re doing, questioning what they’re doing. That’s really important to see because you don’t want to make a film that just shows the high moments, the successful moments. To really understand what change takes, it involves going deeply into the failures as well.

H2N: The ending of the film is necessarily open ended, because of course the story continues to the present day. And that’s something else Khalid says, that it’ll decades to know whether the revolution succeeded. I know that you shot up until the last possible minute. I was wondering if you had more stuff that you shot that you didn’t have time to edit for the finished version of the film, or if you were continuing to shoot today?

JN: Well, the revolution continues, but the story in the film is at a place where we’re very satisfied [that it] stands on its own and will not be added to. The first cut was a political story from the bringing down of the president to the election of a new president, but this final cut has really gotten at the full emotional journey of the characters. We hope people will continue to go to our website, where we’ll be uploading clips of what is happening now and showing possibly some of the footage that did not make it into the cut, some very revealing moments, if people are interested. It’s kind of like DVD extras but now we’re able to put it online. But [as far as the release version] it doesn’t matter what events come. This film stands on its feet five years, fifty years, a hundred years from now because it tells the story of a time when these protesters fought against every single large force that exists in much of the world today, whether that force be a corrupt leadership, a military fascist regime, or a religious fascist regime. These are the strains of fascism that these organized social movements are fighting right now.

— Nelson Kim

Pingback: Daily | NYFF 2013 | Jehane Noujaim's THE SQUARE - Fandor: Keyframe Editorial Hub for Cinephiles