A Conversation with Greta Gerwig (LADY BIRD)

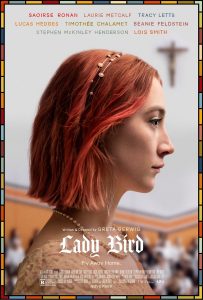

I met with writer/director Greta Gerwig, heretofore best known as an actress in films like Frances Ha and Mistress America, on Sunday, October 22, 2017, at the Middleburg Film Festival as part of a press roundtable with three other critics: Mae Abdulbaki, of Movies with Mae; Hannah Buchdahl, of Chickflix; and Leslie Combemale, of Cinema Siren. We were there to discuss Gerwig’s solo directorial debut, Lady Bird (she had previously co-directed Nights and Weekends with Joe Swanberg). The film is a sweet-and-sour coming-of-age tale starring Saoirse Ronan as a Catholic schoolgirl in Sacramento (Gerwig’s hometown). We join her in her senior year, just as her relationship with her mother, played by the incomparable Laurie Metcalf, is growing complicated. With a terrific ensemble cast that also includes Tracy Letts (The Lovers), Lucas Hedges (Manchester by the Sea) and Timothée Chalamet (Love the Coopers), as well as relative newcomer Beanie Feldstein, Gerwig works wonders trafficking in the seemingly ordinary travails of adolescence that are anything but. Underneath it all, the subtle brilliance of her writing and directing mask the precision of her craft. Hers is a great talent behind the camera, and we should all be grateful that she gifted us this charming movie. Here is a condensed digest of the five-way conversation, edited for clarity and (relative) brevity. I was only able to ask two questions, myself, but I include the entire discussion, clearly labeling who asked what. My apologies if I mistakenly alter a word or two of my colleagues’ questions. All mistakes are my own. Enjoy!

Cinema Siren: The title “Lady Bird” comes from the children’s rhyme “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home. Your house is on fire and your children all gone.” I’m interested in the idea of home and what in means in terms of identity and how that plays into the film.

Cinema Siren: The title “Lady Bird” comes from the children’s rhyme “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home. Your house is on fire and your children all gone.” I’m interested in the idea of home and what in means in terms of identity and how that plays into the film.

Greta Gerwig: That’s interesting. I didn’t consciously understand why I chose the name “Lady Bird,” but I was just working on the script, and writing different scenes, and I felt like I kept hitting some sort of block, and I put everything aside and wrote at the top of the page, “Why won’t you call me Lady Bird? You promised that you would.” And I thought, “Who is this person? Who is this person who makes people call her by this name?” And, in retrospect, I also remembered that rhyme and thought about the act of renaming and what that means, and how it can be either a religious act or a secular act.

CS: As in confirmation…

GG: Confirmation! You choose your saint name, and you choose the thing you’re trying to emulate and the space you’re trying to occupy. Or, if you want to become a rock star or a movie star, you choose the name Marilyn Monroe or…David Bowie. Those aren’t their names. They chose things bigger than themselves. And what’s interesting to me is that it has a double meaning, which is that you sort of have this supreme confidence in yourself that you can be bigger than you are, and it also has a deep insecurity embedded in it, which is that you are not enough.

And I think, for me, being able to grapple with home, and what home means and how it’s something that only makes sense as it retreats from you, or you leave it, is so much a part of that, because I think that accepting where you’re from and incorporating that into who you become is complicated…especially for teenagers. I don’t know very many teenagers who think, “I’m great just as I am, and where I’m from is awesome.” There’s all this stuff built in at that age where you feel like you’re wrong, the place is wrong, and the certainty that life is happening someplace else, and that you’ve just got to get to the life that’s happening another place … and once you get there, you realize that life was going on all the time.

Chickflix: Were you concerned at all about the title? I assumed, without knowing anything walking in, that it was a Lady Bird Johnson biopic, in part because last year, Jackie premiered here at Middleburg. So, I was just wondering if that caused anyone any pause throughout the time of putting this together.

GG: No.

Chickflix: So, everyone was good with it?

GG: Yes.

Chickflix: Did you have any alternate titles along the way, or was that pretty much it?

GG: Well, my original title when I was working on the script – the very long version of the script – was “Mothers and Daughters,” but “Lady Bird” was always the title. I love the name, I love the way it sounds, and no one ever…of course, you don’t want people to think it is about Lady Bird Johnson and then be disappointed…

Chickflix: I don’t think they’d be disappointed…(laughs)

GG: You know, it’s very rare that people walk in totally blind to a movie, anyway, so you figure if they’re going they have some sense of what it’s about.

Our Chris Reed and Writer/Director Greta Gerwig

Hammer to Nail: We’ll see how it shows up in the Netflix algorithm…

GG: (laughs) I know…that’s right! The all-powerful algorithm…

HtN: So, I really liked the way the film looked, and I was reading in the press notes about your working relationship with the DP [director of photography] and production designer, and I just wanted to ask you about the particular challenges of creating a world in the fairly recent past. It takes place in 2002, only 15 years ago. In some ways, I think it might be more difficult than doing something in the distant past, because it almost looks like the present, but not quite. What were some of the ways you went about creating that look?

GG: Well, we always wanted it to feel a bit like a memory, without being too cute about it. The DP and I had a ton of images and references that we looked at, from other films, particularly a film by John Huston, Fat City, which takes place in Stockton – it’s a boxing movie – and Stockton is quite close to Sacramento and has that same light and that same look and color palette. And then also Fellini’s Amarcord, because that movie is so much about childhood and about memory, and there’s a reality to it but also a heightened quality to it, so it feels like memory. So, we wanted to strike this balance between what was real and what was kind of elevated to a fable, in the telling of it.

And in terms of the time period, we talked a lot about the fact that right after 9/11, the country was in a sort of collective shock. And it was also before the internet really became everything, and so the culture was not…now everyone has access to everything all the time, and in the way it looked and the way it felt, it’s not like people had Pinterest boards, or Spotify to direct them to cool new music. You wouldn’t know about certain things unless you knew the guy at the record store who was going to give you the Kinks album, or something. You would know what knew from the radio. You would know about the fashions you knew from magazines.

And even things like IKEA didn’t exist. There wasn’t this ability to have a certain kind of taste be everywhere. In the family house you grew up in, there would still be furniture from your grandmother’s house, and then maybe a computer chair from Costco. There wasn’t this more unified look to everything, and it was still more connected to the past. So, it was a very detail-oriented process of how to capture that. And there would also be tracers from the ’90s. It wasn’t like every song on the radio was from 2002: there were still hits from the ’90s being played. There were clothes and cars on the road from the ’90s, in addition to the brand new things. It was about getting that realistic vision of time, and not just about that year.

Movies with Mae: Saoirse Ronan is incredible in this film. In a previous interview, you mentioned that when she initially did the reading, she performed the character very differently than you had envisioned her, in your head. What did she bring to the role that you had not envisioned?

GG: Well, sometimes that’s hard to articulate. She has a quality of being emotionally always at a 10. Her investment level is always at 100%, and she always works from this place of truth. So the comedy is always played from the inside, without any quotation marks around it, which I think some comedic performances often have. And so, the moments that are funny, or the moments that are painful, or the moments that are awkward are just so lived-in that you don’t feel that you’re watching a performance; you feel like you’re experiencing it with her. It just had that quality … it’s hard to describe, but it felt all heightened, to me. She has the ability to throw away lines, but really nothing when you’re 17 is really thrown away, truly. It’s all so vivid.

CS: My experience with talking to women filmmakers is that they’re very centered in collaboration. It’s very much a committee experience, even though you’re in charge of making it all come together. Could you talk a little bit about your perspective on collaboration, as a woman in film, and how it influenced your experience as a director?

GG: Sure. I think film is one of the most deeply collaborative arts, whether you’re a man or a woman. It is like theater in that way, with all these people coming together. If what you want is total artistic control, you should be a novelist. It’s all yours. But in film, even people who seem as if they’re ruling everything with an iron fist, there’s just no way you can, and I don’t think there’s anyway that you’d want to. I think, for me, I always had a very clear idea of how it looked, and sounded, and should be put together. In most films, you have to know your true north, with your own compass, because everyone can only really bring their collaborative efforts to you if you know what you’re going for. And ultimately, what you do is to get everyone to dream the same dream you’re dreaming. So, you collaborate to hypnotize everyone to the same place, so that we’re all making the same film.

Saoirse Ronan and Beanie Feldstein

And it’s a paradox, because that certainty and that gut feeling and that true north come from you, and that is what makes it collaborative. I love people bringing their whole selves to it. For example, with the actors, I’m a very involved director, and in terms of the script, we don’t change any of the lines, and I do a lot of takes, and I give a lot of feedback, but also, I feel like there’s this very important moment during the rehearsal process where I give the flame of the character to them. And at that point, I don’t know more about about that character than they know. You have to give your actors that trust, otherwise they’ll never be able to fully inhabit it, if you keep it too close to yourself. So it’s this thing of giving it away and trusting that it will come back.

CS: So, it’s about trust, too.

GG: Oh, hugely. That’s why I take a long time in building my creative team, because these are the people you’re going to be making this movie with, and of course the actors are the ones that everyone sees on screen, but every single person, down to the PA [production assistant], contributes to how that movie feels, and every single person has to be a storyteller, even the people in accounting, even the people making the schedules every day. Everybody has to be a storyteller.

HtN: Speaking of your creative team, I was very impressed with the economy of your editing, in terms of the way you get a lot of information across very succinctly, right from the beginning, in terms of how you set up the space.

GG: Thank you!

HtN: Could you talk, then, about your collaboration with editor Nick Houy?

GG: You know, hiring an editor is a big leap of faith, because it’s…well, you can’t know until you know, and you really spend a lot of one-on-one time with an editor, just you and them, sitting in a room, and all you have to go on is their reaction to the script. And Nick was very intelligent about the script, and very detailed about the script, and I felt like he was inside the story from the very beginning, which ultimately is the best thing to go off of. He came as a recommendation through an editor whom I had worked with on Frances Ha and Mistress America, Jen Lame, who also edited Manchester by the Sea and is one of the great editors right now, but was unavailable to work on this, and she said, “I have a friend and I think you guys would really hit it off.”

And Nick always heard the rhythm of the script, and he saw what I was trying to do. Right away, when we started working on it, I wanted it to have this tumbling-forward quality, where it felt like time was moving faster than people could hold on to it, even in terms of little things, like pre-lapping dialogue before a scene, where you feel like you’re being pulled into the future.

HtN: That was one of the things I really noticed, were your L cuts and J cuts.

GG: And then, also, it goes to the way we shot it, which is that I wanted it to feel very simple, but very placed, that everything was just so: we’re showing you just enough of this room so that you know that this is a motel room; we’re showing you just these details. I didn’t want it to feel like I was just making pretty shots for no reason; I wanted it to feel very economical. When I was talking to my DP, Sam [Levy], we’d have this catchphrase, where we’d say, “Every shot should be plain and luscious.” That was something that we tried to do all the way through the film. And that kind of editing, which was both living in the moments of what’s unsaid, as much as what’s said, and with this staccato rhythm that’s playing with the rhythm in the language, that’s what Nick was so good at accomplishing.

Chickflix: I know this isn’t truly autobiographical, or semi-autobiographical, but you know the time and you know the place and you know the characters, and you’ve created this world…do you have any notion of revisiting this character at some point? Could you see yourself doing a before or after trilogy?

GG: You know, I think my love of cinema has to do with the finite nature of it. I think, speaking to the editing, that where we cut off on that final intake of breath, on feeling that that’s the ending of this story, that when she then will breathe out, that’s a new story and I’m not telling it. I love those cuts at the end where you feel like it’s almost a beat before it’s sunk in for you, and then it’s gone. And it’s a sad feeling, but it’s a wonderful feeling, in cinema. It was this flickering light and sound, and then it’s gone. And I think, for me, that I think of this film as telling this story with these parentheses around this life. And if I change my mind later, I’ll eat my words, but I tend to think of films as their own little universes.

Chickflix: And in this case, it’s your universe.

GG: It’s my universe. And in the next film, they’ll all be vampires. (laughs)

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)